Girls on Film: The confounding problems of fan fiction

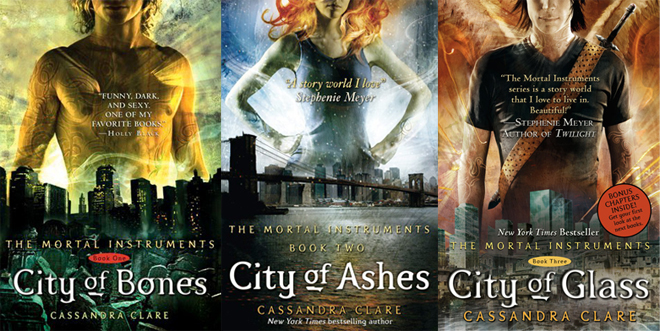

The disappointing new film The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones was derived from a piece of Harry Potter fan fiction. That's not a good thing.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones is upon us — a maelstrom of every fantasy trope imaginable funneled through 130 minutes of teenage angst.

Lily Collins stars as Clary, a girl sucked into a world of werewolves, vampires, and other underworldly things lurking just out of sight in downtown Manhattan. But surprise, surprise, it turns out that Clary isn't a regular teen; she's a lost Shadowhunter (tasked with keeping a "Downworld" of demons in check) who's been hidden in the human world by her mom. Unfortunately, mom is now missing, and Clary must find her — with the help of sexy, towheaded Shadowhunter Jace (Jamie Campbell Bower).

The rotten reviews are pouring in. It's "an almost random collection of sexy-supernatural teen signifiers," overstuffed like a "checklist of stuff that sells young adult fantasy fiction" with "too many characters" — "just a variation on a theme which leaves little else that hasn't been done in some way before in other fantasy franchises."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones is based on the YA series of the same name by Cassandra Clare — but its origins go back further than that, to a series of Harry Potter fan fiction stories collected under the title The Draco Trilogy. Though The Mortal Instruments has long been scrubbed of any direct references to the Harry Potter franchise, its suspiciously derivative narrative makes a lot more sense in its original context.

To be fair, fan fiction is neither a new invention nor an inherently questionable one. The term "fan fiction" gained popularity along with the rise of the internet, but a version of "fan fiction" has been the driving force behind the evolution of centuries-old stories, which were told, retold, and expanded by a wide range of storytellers — resulting in some of the most beloved stories in history. The practice has created classics like West Side Story (based on Romeo and Juliet, a story that didn't originate with Shakespeare anyway). Disney used a version of fan fiction to change grotesque fairy tales into family-friendly animated musicals. Aspiring television writers show off their chops by writing "spec scripts" for their favorite series. And fans write these stories as a means to let their beloved series continue for years after their official entries have concluded — even if the practice angers writers like Anne Rice, Orson Scott Card, and Ursula K. LeGuin.

But fan fiction has suddenly become the new big business — a way for fans (and publishers) to capitalize on a recently established writer's world and hope to ride the same waves of success. E.L. James channeled Stephenie Meyer's pent-up Twilight lust into Master of the Universe — a popular BDSM fanfic about Edward and Bella until she plugged in new names and sold it as Fifty Shades of Grey. The best-seller made James Forbes' most recent top-earning author with a staggering $95 million annual take and a movie deal. Similarly, Cassandra Clare leveraged her Draco Malfoy fanfic into a book deal that's already seen multiple trilogies and this week's problematic film.

But The Mortal Instruments is even more derivative than James' Fifty Shades trilogy. This isn't a specific universe, re-imagined and sold under new names; it's a hybrid of elements cribbed from Clare's favorite stories. Her work first became popular (and controversial) not because she took J.K. Rowling's world and imagined all-new stories, but because she used it as a template in which she could fit in all of her other pop culture fandom — inserting quippy exchanges from Buffy the Vampire Slayer and passages from authors like Pamela Dean (as this expose detailed) with only minimal changes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's no surprise that critics are down on the mishmash of elements in the new film. Clare may have stopped copying her favorite pop culture quotes into her work verbatim, but it's still a variation of the same patchwork pop quilt.

The title "Mortal Instruments" was first used for a Ron and Ginny-focused Harry Potter fanfic in 2004, and The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones borrows from that story and Clare's Draco Trilogy to craft its heroes Clary — a carbon copy of Ginny Weasley whose name immediately echoes "Harry" — and Jace (a blatant carbon copy of Harry Potter villain Draco Malfoy). They enter a domain that's hidden in plain sight in the muggle "mundane" world. Magic obscures their metropolitan residences, which lie far from their homelands, where the Clave — the governing body completely out of touch with the rising danger — resides. The Shadowhunters' wands are called "steles"; many of their names echo names Harry Potter came across (Ravenclaw/Ravenscar); and they even suffer similar plagues (dragon pox/demon pox). They're fighting against Voldemort Valentine, a powerful Shadowhunter with a circle of like-minded followers who were eager to purify the bloodline until a brief war seemed to kill the villain — right after he and his followers had the children who must now save the world. They hunt not for three "Deathly Hallows," but three "Mortal Instruments," which would bring great, catastrophic power to Valentine, who happens to have followers in some of the adults the now-grown children trust. Is any of this sounding familiar?

Making matters worse, the film doesn't relay Clare's fandom. Instead, it plays like a fan fiction of Clare's original fan fiction frenzy — a copy of a copy until motivations and storylines become obscured and nonsensical. Instead of pleasing fans with a faithful story, motivations both simple and complex are changed. The heroism Clary and Simon show on the page becomes moments for the Shadowhunters on the screen to save them. Every scene is laced with new conspiracies and stupidity, and — fearing subtlety and an anticlimactic Breaking Dawn-esque showdown — the climax is overstuffed with new demons, threats, and twists intended to up the action, which only obscure any comprehensible plot development.

This is the trouble with carbon-copying creativity. The professional fan fiction stories that are currently making their own pop-cultural waves approach writing as a plug-and-play practice without the creativity that fueled the original stories. At its most mundane, it results in confusion (for baffled, unintiated viewers like Kyle Smith, who thought teen Jace was a thousand years old as he parsed the film's many fantasy elements). At its worst, it becomes a signpost of offensive cluelessness. In Fifty Shades of Grey, James treated race as interchangeable by plugging in the Hispanic "Jose" for Twilight's Native American Jacob. In her work, race can simply be changed by dropping a few idiosyncratic Spanish phrases, as Jose utters "Dios mío" over and over again.

This kind of nakedly derivative fan fiction lacks the depth that makes reading and cinema worthwhile, and misses the heart of storytelling: Discovery. We don't crack open books and go to movie theaters for the expected; we explore for the unexpected. J.K. Rowling didn't become a billionaire by echoing someone else's work. Harry Potter became a global phenomenon because she reimagined old tropes into a world readers and viewers had never seen before. Rowling crafted a world that piqued curiosity, rather than just relaying a world in which every scene is familiar, and every twist is obvious.

There's definite promise in the core concept of Mortal Instruments; how could you not be curious about a world where soldiers inflict painful tattoos upon their flesh to fight evil, and a spunky young girl turns out to be one of the most powerful soldiers who ever existed? But until a story is willing to break through the boundaries of its inspiration and drop the mimicry in favor of its own voice, it will always be as derivative as its origins — no matter how many names you change.

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.