Why is American internet so slow?

The country that literally invented the internet is now behind Estonia in terms of download speeds

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

According to a recent study by Ookla Speedtest, the U.S. ranks a shocking 31st in the world in terms of average download speeds. The leaders in the world are Hong Kong at 72.49 Mbps and Singapore on 58.84 Mbps. And America? Averaging speeds of 20.77 Mbps, it falls behind countries like Estonia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Uruguay.

Its upload speeds are even worse. Globally, the U.S. ranks 42nd with an average upload speed of 6.31 Mbps, behind Lesotho, Belarus, Slovenia, and other countries you only hear mentioned on Jeopardy.

So how did America fall behind? How did the country that literally invented the internet — and the home to world-leading tech companies such as Apple, Microsoft, Netflix, Facebook, Google, and Cisco — fall behind so many others in download speeds?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

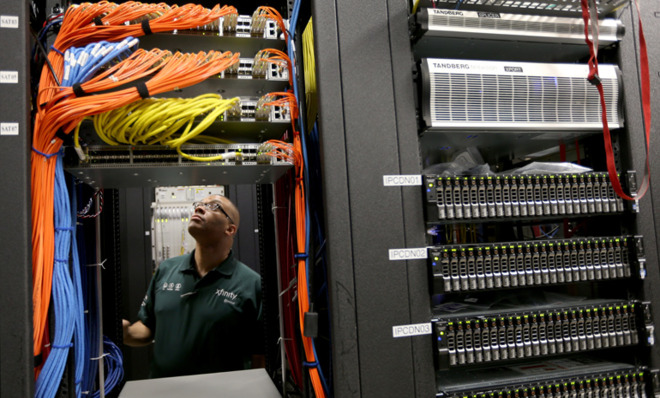

Susan Crawford argues that "huge telecommunication companies" such as Comcast, Time Warner, Verizon, and AT&T have "divided up markets and put themselves in a position where they're subject to no competition."

How? The 1996 Telecommunications Act — which was meant to foster competition — allowed cable companies and telecoms companies to simply divide markets and merge their way to monopoly, allowing them to charge customers higher and higher prices without the kind of investment in internet infrastructure, especially in next-generation fiber optic connections, that is ongoing in other countries. Fiber optic connections offer a particularly compelling example. While expensive to build, they offer faster and smoother connections than traditional copper wire connections. But Verizon stopped building out fiber optic infrastructure in 2010 — citing high costs — just as other countries were getting to work.

We deregulated high-speed internet access 10 years ago and since then we've seen enormous consolidation and monopolies… Left to their own devices, companies that supply internet access will charge high prices, because they face neither competition nor oversight. [BBC]

If a market becomes a monopoly, there's often nothing whatever to force monopolists to invest in infrastructure or improve their service. Of course, in the few places where a new competitor like Google Fiber has appeared, telecoms companies have been spooked and forced to cut prices and improve service in response to the new competition. But that isn't happening everywhere. It's very expensive for a new competitor to come into a market, like telecommunications, that has very high barriers to entry. Laying copper wire or fiber optic cable is expensive, and if the incumbent companies won't grant new competitors access to their infrastructure, then the free market forces of competition don't work and infrastructure stagnates, even as consumer anger and desire for competition rises due to poor service.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Other countries have done more to ensure that the market is open to competition. A 2006 study comparing the American and South Korean broadband markets concluded:

[T]he South Korean market was able to grow rapidly due to fierce competition in the market, mostly facilitated by the Korean government's open access rule and policy choices more favorable to new entrants rather than to the incumbents. Furthermore, near monopoly control of the residential communications infrastructure by cable operators and telephone companies manifests itself as relatively high pricing and lower quality in the U.S. [Professor Richard Taylor and Eun-A Park via Academic.edu]

And the gap between the U.S. and Korea has only grown wider since then.

The idea of a regulated market being more conducive to competition may be alien to free market ideologues, but telecoms and internet is a real world example of deregulation leading to monopolization instead of competition in lots of markets.

The Obama administration is trying to undercut the whole mess by building new publicly-funded wireless networks to offer fast 4G internet across the U.S. Whether this public investment will really prove effective at bringing internet competition to monopolized markets — and nudging the highly profitable private companies like Time Warner and Comcast into improving their services — remains to be seen.

So, many — including Crawford and others — are now calling for stronger regulation of the existing market. At The New Yorker, John Cassidy argued last month:

What we need is a new competition policy that puts the interests of consumers first, seeks to replicate what other countries have done, and treats with extreme skepticism the arguments of monopoly incumbents such as Comcast and Time Warner Cable. [The New Yorker]

But he's skeptical we'll get it, noting that: "The new head of the Federal Communications Commission, Tom Wheeler, is a former lobbyist for two sets of vested interests: the cell-phone operators and, you guessed it, the cable companies."

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention