The contentious policy at the heart of Cliven Bundy's armed standoff with the government

The federal government owns the Nevada cattle rancher's grazing land. Should it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy has been illegally grazing his cattle on federal land for more than 15 years. On Saturday, Bundy, his family, and dozens of armed supporters convinced the federal Bureau of Land Management that confiscating Bundy's cattle wasn't worth human bloodshed.

"Based on information about conditions on the ground, and in consultation with law enforcement, we have made a decision to conclude the cattle gather because of our serious concern about the safety of employees and members of the public," newly sworn-in BLM Director Neil Kornze said in a statement. "We remain disappointed that Cliven Bundy continues to not comply with the same laws that 16,000 public lands ranchers do every year.... Mr. Bundy owes the American taxpayers in excess of $1 million. The BLM will continue to work to resolve the matter administratively and judicially."

Of course, it was the long lack of administrative and judicial success that led to last week's BLM operation to round up and impound Bundy's cattle. Bundy stopped paying grazing fees to the federal government in 1993, after the BLM changed the terms of the grazing allotment near Bunkerville, about 80 miles northeast of Las Vegas along I-15. The BLM canceled his permit, and when that didn't work, it took him to court.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 1999, the Nevada district court permanently barred Bundy from grazing his cattle on the land, charging him $200 per animal per day they remained on the land; the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the injunction. That is where the most of the $1 million fine comes from.

Bundy's defense is threefold: He claims his family has been raising cattle on the land since 1877, before the BLM existed, so his rights to the land trump the federal government's; he asserts that Nevada really owns the federal lands — a radical offshoot of the long-simmering Sagebush Rebellion — so he should only pay grazing rights to the state or local government; and he has guns.

The courts didn't agree with Bundy's first two defenses. But the three combined make for a pretty strong emotional case, and that drew more than 100 kindred spirits from across the West, notably some heavily armed members of the Operation Mutual Aid militia, to help him defend his claim.

"If you believe in the authority of the federal government over public lands — established unequivocally in the U.S. Constitution — there is ample justification for the impoundment," says Christi Turner at High Country News.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But Bundy and his allies don't seem to care much for federal authority over public lands. On Saturday, after reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, singing the national anthem, and saying a few prayers, the armed gathering drove and rode horses to the BLM's holding pens to demand the release of the some 400 head of cattle the federal government has seized. A tense, four-hour standoff ensued, with each side pointing guns at the other.

Clark County Sheriff Doug Gillespie negotiated the end of the standoff, with the BLM essentially throwing in the towel: It released the cattle and started closing down the cattle-grabbing operation. It's hard to fault the agency for stepping back to avoid an armed conflict — a bloody confrontation would have been good for nobody — but it wasn't exactly a shining moment for the rule of law.

The BLM was enforcing a court order (read it here), and Bundy has been flouting the law for 20 years, illegally grazing his cattle on land that isn't his and without permission. His supporters raised weapons at federal agents. "We were dedicated to opening those gates and peacefully walking through to retrieve those cattle," Ammon Bundy, one of Cliven Bundy's 14 children, told Reuters. "The presence of weapons was needed in order to intimidate them."

Cliven Bundy, apparently buoyed by his success, ordered Gillespie to disarm all BLM rangers on federal land — the sheriff wisely ignored that ultimatum.

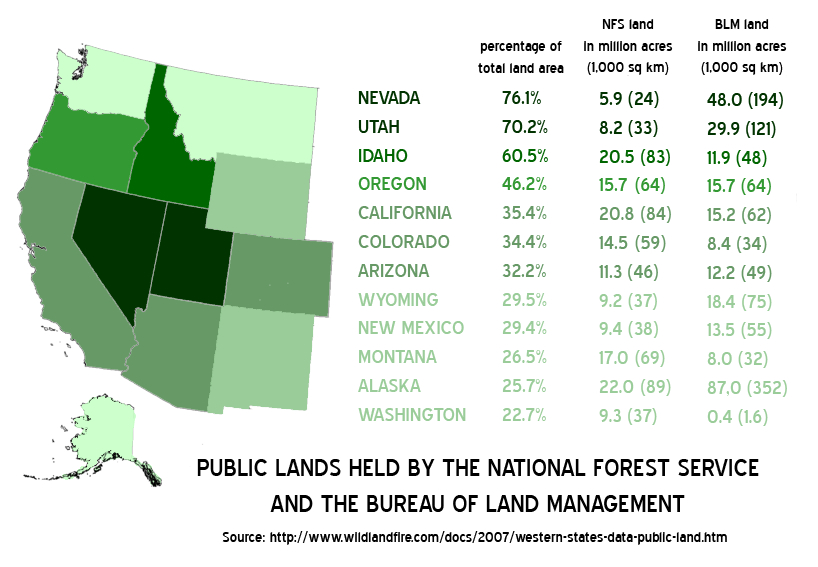

But let's look at Bundy's larger point, that the federal government shouldn't control 87 percent of Nevada and 60 percent of the 12 states in the West. This includes many of the country's most beautiful national parks, forests, and wilderness areas, but also huge swathes of scrub lands, timber forest, and areas with mineral and energy wealth.

It is sort of an accident of history and because of the whims of Congress that the federal government controls all that land. In the mid-1800s, lawmakers passed laws encouraging settlers to colonize the West, with the idea of carving up the new U.S. territories into privately held parcels. Starting with Theodore Roosevelt, though, U.S. lawmakers started to conserve public lands for the public with the creation of the national parks.

In 1934, Congress created the U.S. Grazing Service to manage cattle and sheep grazing on public lands, and in 1946 the Grazing Service was combined with the General Land Office to create the BLM. In 1976, Congress passed the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, formally setting aside federal public lands for multiple public uses, including recreation, ranching, and mining. The BLM, Forest Service, and National Park Service have been juggling those competing interests ever since.

For Bundy to have the right to graze his cattle in Gold Butte/Bunkerville area, the U.S. government would have to sell him the land, cede it to Nevada, get the area's endangered species removed from the endangered list, and/or lose to Bundy in a court of law. What seems certain is that this standoff isn't over. Even if Bundy and the BLS reach an amicable settlement, the inherent conflict will always fester between environmentalists and hikers who want to preserve the land and ranchers, miners, foresters, and motor-vehicle enthusiasts who want to be a little rougher on the public lands.

In other words, even if we cede the argument to Woody Guthrie that this land is your land and this land is my land, we'll always want to use the land for different purposes. The many Westerners who live on or near these public lands have a point when they complain about being restricted in what they can do near their homes largely so people in the big cities — Seattle, Denver, Portland — and the public lands–sparse East Coast have someplace to hike and camp and fish.

But personally, I'd rather err on the side of having that fight than losing the argument to private developers. So far, Congress agrees.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.