How optical illusions trick your brain, according to science

Yes, your eyes do deceive you

Look closely at the picture above. What you're actually looking at is a work of art by Johannes Stotter. Despite its extremely photographic nature, it's actually a painting.

Even more shocking is the canvas isn't cloth. It's a woman covered in body paint.

Stotter's work takes advantage of the fact that our eyes skim and our brains tend to jump to conclusions. The act of seeing something begins with light rays bouncing off an object. These rays enter the eyes through the cornea, which is the clear, outer portion of the eye. The cornea then bends or refracts the light rays as they go through the black part of your eye, the pupil. The iris — the colored portion of your eye — contracts or expands to change the amount of light that goes through.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Finally, the light rays go through the lens of your eye, which changes shape to target the light towards your retina, the thin tissue at the back of your eye that is full of nerve cells that detect light. The cells in the retina, called rods and cones, turn the light into electrical signals. That gets sent through the optic nerve, where the brain interprets them.

The entire process takes about one-tenth of a second, but that's long enough to make your brain confused sometimes, evolutionary neurobiologist Mark Changizi told Discovery News.

By arranging a series of patterns, images, and colors strategically, or playing with the way an object is lit, the brain can be tricked into seeing something that isn't there. How you perceive proportion can also be altered depending on the known objects that are nearby. It's not magic — it's an optical illusion.

For example, Changizi pointed out that when we move and look at something, the image becomes a blurry line in our vision. Because our brains associate those blurred lines with motion, static pictures that feature fuzziness tend to look like they are moving at warp speed.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

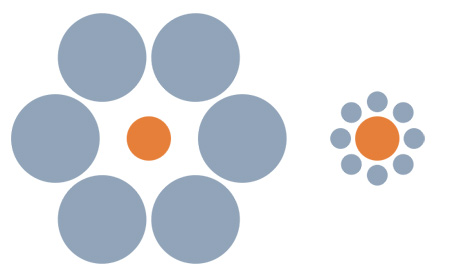

There's also the Ebbinghaus illusion, or Titchener circles, which messes with how we judge the size an object.

It's all relative. When two circles that are exactly the same size are put next to each other, but one circle is surrounded by larger circles and the other one by smaller ones, the circle surrounded by the larger spots tends to seem smaller than its counterpart.

Technically, Stotter's image isn't a traditional optical illusion. But it uses some of the same principles.

Using paint, the artist softens the harsh lines of the body and creates shadows using light and dark colors next to each other. He also has the model contort her body so that her shape looks like the outline of a parrot. All the details that don't make sense — for example, her bent leg creating the wing, or the fingers of her white hand that makes up the beak — are glossed over by your brain because everything else makes sense.

If you're a fan of his work, check out his earlier project: a frog created out of five people.

Michelle Castillo is a freelance writer and editor and a pop culture junkie. Her work has appeared in TIME, the Los Angeles Times and CBS News.

-

Jane Austen lives on at these timeless hotels

Jane Austen lives on at these timeless hotelsThe Week Recommends Here’s where to celebrate the writing legend’s 250th birthday

-

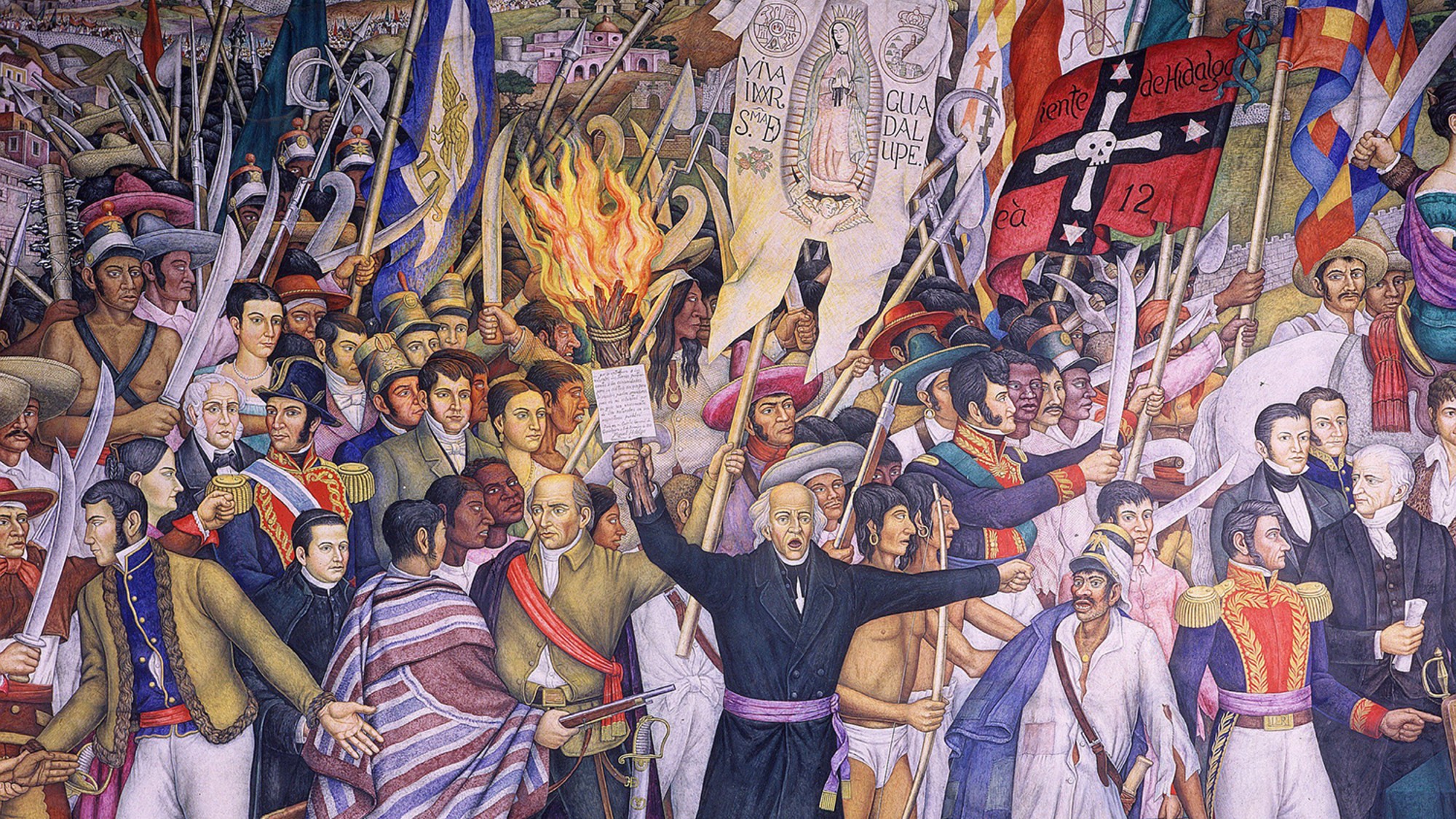

‘Mexico: A 500-Year History’ by Paul Gillingham and ‘When Caesar Was King: How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy’ by David Margolick

‘Mexico: A 500-Year History’ by Paul Gillingham and ‘When Caesar Was King: How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy’ by David Margolickfeature A chronicle of Mexico’s shifts in power and how Sid Caesar shaped the early days of television

-

GOP wins tight House race in red Tennessee district

GOP wins tight House race in red Tennessee districtSpeed Read Republicans maintained their advantage in the House