What if economic growth is no longer possible in the 21st century?

The postwar economic model is no longer sustainable or effective. That means we must turn to redistribution if we want to save the middle class.

For decades, rapid economic growth has been the norm for developed countries. An educated workforce, a large population boom, major technological advances, and abundant fossil fuels were the key components of growth, generating substantial and broadly distributed increases in standards of living in many countries. We have grown so used to such growth that we inevitably view it as a panacea for a host of economic ills, whether it's a deep recession or income inequality.

We now understand, however, that the postwar growth paradigm is not environmentally sustainable. We also know that the shared prosperity it once delivered is itself unraveling. With these combined trends, something has to give in order to maintain living standards.

One possible scenario, with surprisingly good news for average Americans, is that constraints on growth will force political leaders to accept redistribution as a policy tool. Indeed, if we cannot grow our way to broadly shared prosperity again, redistribution is the only way to save the middle class.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Many economists have warned that the old model is dying out. In a much-cited paper, Robert Gordon argues that the rapid growth we take for granted is not only historically anomalous but likely to slow significantly in the 21st century, pointing in particular to diminishing returns from technology as one major drag. Developed countries have already picked the "low-hanging fruit" of technological advance (in Tyler Cowen's phrase), and future innovations will produce far less growth, he argues.

Steven King, chief economist at HSBC, similarly argues, "The underlying reason for the stagnation is that a half-century of remarkable one-off developments in the industrialized world will not be repeated." Gordon also points to rising inequality, which has led to stagnating middle-class wages, as a drag on future growth. As a result of these trends and others, average annual growth will fall below 1 percent in the 21st century, he predicts.

Then there is the impact on the global economy that will result from combating global warming. Working from a conservative carbon budget of 450 parts per million (PPM), Humberto Llavador, John Roemer, and Joaquim Silvestre predict that achieving this target will require a substantial slowing of growth, mainly borne by the United States and China. The U.S. and China must keep growth within the threshold of 1 percent and 2.8 percent of GDP per year, respectively, for the next 75 years, they say.

In an interview, Roemer tells us that these results are optimistic; after all, some economists have argued that growth may not occur at all. In the paper, the three argue that "there is no politically feasible solution to the climate change problem unless" both the U.S. and China "honestly recognize the connection between restricting emissions and curbing growth." In contrast, the Congressional Budget Office's long-range analyses use a growth projection of 2.2 percent on average over the next 75 years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Other economists have come to similar conclusions about the connections between growth and sustainability. Early in 2012, Kenneth Rogoff argued that maximizing growth must be weighed against the negative possibilities of growth, like global warming. Indeed as James Gustave Speth notes, environmental impacts are the most significant challenges to growth: "Economic activity and its growth are the principal drivers of massive environmental decline."

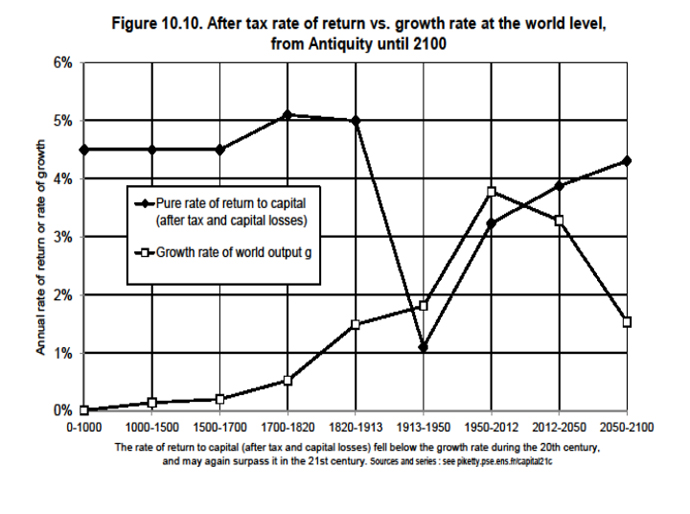

Growth constraints will push the issue of distribution to the forefront of political discussions. In his forthcoming book Capital, Thomas Piketty predicts that growth will slow to between 1 and 2 percent — 19th-century levels — by the end of the 21st century. This trend, he further argues, will be accompanied by higher returns to capital and lower returns to labor, thereby exacerbating inequality.

The conclusions that flow from these observations are stark. The old economic paradigm relied on unsustainable growth, so we must change the paradigm. For decades, our rising standard of living came at a deep cost to our environment and our children's future. There is simply not enough planetary bio-capacity to grow our way out of the messy moral discussions of distribution. The idea that inequality is merely an inefficiency to be corrected with a technocratic fix or perpetual growth is no longer tenable.

Fortunately, we have plenty of GDP that could help the middle class, with approximately $200,000 a year potentially available for each family of four. Given that the median family of four only gets about $67,000 a year at this point, it should be clear that it is possible to grow and strengthen our middle class, significantly, while adjusting to the lower GDP growth we are likely to experience in the future.

The question is, will political leaders accept the need for distributional remedies, or will they continue to side with the wealthy against the struggling middle class?