Why we shouldn't celebrate Mandela's militancy

Bob Herbert writes that Mandela's "primary significance" was his "resolve to do whatever was necessary." He's wrong.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

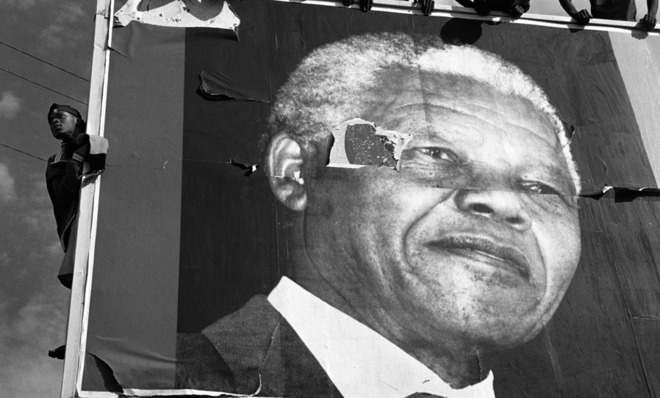

While most Nelson Mandela tributes highlight his dignity while incarcerated and his magnanimity toward his former foes once free, there is a strain of commentary on the left arguing we should also emphasize, and even celebrate, the violent militancy that led him to prison in the first place.

Bob Herbert writes in Jacobin that Mandela's "primary significance" was not his "willingness to lock arms or hold hands" with his former oppressors, but his "unshakable resolve to do whatever was necessary to bring those enemies to their knees" and the "fierceness" of his "militancy." Salon's Natasha Lennard argues, "Attempts, notably by white liberals, to enshrine Mandela as a peaceful freedom fighter do no justice to his actual fight." The Grio's David A. Love proclaims, "we must celebrate it all… You cannot take the statesman without embracing the militant. They are one and the same."

It's true that history would be poorly served if we looked away from any aspect of Mandela's life story. But should we treat Mandela's militant period as part of what made him great? Is the ultimate lesson of Mandela that we should extend a hand to our enemies or that violent oppression should be met with violence?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's not hard to make the case that Mandela and his African National Congress — which had long practiced nonviolence — was justified in altering its course after the South African government outlawed their organization and massacred peaceful protestors. One could further argue that the ANC's continued bomb attacks in the 1980s compelled the apartheid government to eventually buckle. As the Los Angeles Times recently detailed, debate continues on whether sanctions or fears of "all-out civil war" prompted the government to free Mandela.

Yet it is not a clear-cut case that the embrace of violence was tactically wise. Consider that it took just under a decade for the American civil

rights movement to go from the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott to the 1964 Civil Rights Act (with several incremental victories along the way), while 30 years spanned between the ANC's 1961 turn toward violence and the end of apartheid.

In his autobiography, Mandela argued Martin Luther King had a luxury which he lacked: A country with constitutional guarantees for free speech. That's true to a point, though America had its share of civil rights martyrs gunned down by police or by white citizens who never faced justice. Still, one could not expect nonviolence in the 1960s South Africa to work speedy wonders. King was facing off with liberal Presidents JFK and LBJ, not South Africa's racist National Party. And America had already taken incremental steps towards equality with the desegregation of the military and public schools. America was progressing while South Africa was regressing.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the fact that South African blacks in the early 1960s were in a worse place than American blacks does not make the case that the ANC's tack toward violence was the fastest path to liberation.

After his long history of academic work on nonviolent social action girded the peaceful overthrow of Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak, Gene Sharp explained to The New York Times about the risk of violent protest: You give autocrats more leeway to crack down. Said Sharp, "If you fight with violence, you are fighting with your enemy's best weapon."

By ceding some moral high ground, the ANC gave the South Africa cover for its systematic oppression — and gave foreign leaders like President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher an excuse to stand on the wrong side of history — thereby weakening the international coalition against apartheid. A redoubled commitment to nonviolence may have led to a stronger, earlier international response and Mandela may not have had to lose 27 years of life in prison to achieve his goal, though achieve it he did.

The morally murky choice Mandela felt compelled to make out of desperation has its defensible, if cold, logic. But it's not the part of his story worthy of a celebration. What made him one of history's greats was how he did not let his cruel incarceration consume him with animosity toward his oppressors. He negotiated with them, governed with them and extended amnesty toward them. In doing so, he secured a stable political transition for South Africa, something which at the time was by no means certain.

Bill Scher is the executive editor of LiberalOasis.com and the online campaign manager at Campaign for America's Future. He is the author of Wait! Don't Move To Canada!: A Stay-and-Fight Strategy to Win Back America, a regular contributor to Bloggingheads.tv and host of the LiberalOasis Radio Show weekly podcast.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day