6 times Hollywood got slavery really wrong

12 Years is a Slave is great, but it's more the exception than the rule

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Director Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave is earning acclaim for its incredibly brutal and realistic depiction of slavery and racial oppression in Antebellum America. Manohla Dargus at the New York Times praised 12 Years a Slave for not getting caught up in the classic depictions of the South’s "paternalistic gentry with their pretty plantations, their genteel manners and all the their fiddle-dee-dee rest."

However, it’s only relatively recently that Hollywood has turned a corner in its depiction of the Civil War and Antebellum America. Here are six times Hollywood really botched that whole not-being-racist-and-glorifying-slavery thing.

The Birth of a Nation (1915)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One of America’s most groundbreaking films is also one of its most racist. It’s hard to outdo a movie with scenes of blackface actors eating fried chicken and drinking whiskey with their shoes off in a state legislature. There are also more men of color attempting to rape white women than you can count. Really, the movie is an epically long 190 minutes, so you’d be counting for a while. Though its cinematography is pretty remarkable for the era, Roger Ebert notes at Roger Ebert.com that certain scenes "are credited with the revival of the popularity of the Klan, which was all but extinct when the movie appeared." Yup, that’s how racist it was.

The Littlest Rebel (1935)

Shirley Temple may have been considered America’s sweetheart, but in this film, the Confederacy claimed her as its own. The opening scene features Virgie Cary (Temple) having her slave Uncle Billy (Bill "Bojangles" Robinson) dance for all her birthday guests, pretty much setting the tone for the movie’s depiction of slavery as benign...even fun! The tap-dancing scene here is more proof.

It’s easy to get swept up in the charm of Temple and Robinson singing "Polly Wolly Doodle." That is, until you remember the film is about a seven-year-old white girl owning a grown black man who actively fears the prospect of being freed by the Yankees. This film wasn’t the only patronizing Temple-Robinson production. The Littlest Colonel has pretty much the same problem, except Robinson is a butler, not a slave, because its Reconstruction.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Gone with the Wind (1939)

No film romanticizes the Antebellum South quite the Hollywood-perfect way that Gone with the Wind does. The movie even opens with the wistful lines "Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave…" and goes down from there. Lamonia Brown at The Grio writes that the slave characters, Mammy, Prissy, and Pork, are all "simple-minded, complacent, even happy in their enslaved existence, and filled with love for their oppressor." Like The Littlest Rebel, it completely hides the horror of human bondage by making slavery seem fun and even necessary to protect African Americans. No biggie, right?

Speaking to America’s own racist hypocrisies at that time, Hattie McDaniels became the first African American to win an Oscar for her portrayal of Mammy, though she was not allowed to accept her award on stage.

Song of the South (1946)

Walt Disney isn’t known as being the most racially sensitive guy. At The Los Angeles Times, historian Neal Gabler writes that the Walt Disney Archives show he "referred to Italians as ‘garlic eaters’ and used a variety of crude terms for blacks." And his 1933 Three Little Pigs depicted the wolf as a Jewish peddler with a Yiddish accent.

But Song of the South takes the cake. Based on the Uncle Remus stories, the kindly former slave Uncle Remus recounts tales of "Tar Baby" and the sneaky Brer Rabbit, a less than subtle stand-in for the stereotype of the sneaky, mischievous slave. It also "makes the black former slaves seem dependent upon and excessively grateful to their former owners," writes Gabler.

After realizing decades later how racist the movie was, Disney has refused to release the movie for sale for over 25 years, and it doesn’t look like Uncle Remus will become part of the happiest place on earth anytime soon.

Southern Fried Rabbit (1953)

Disney wasn’t the only animator to make oddly racist Civil War cartoons. Apparently, Yosemite Sam falling off a cliff wasn’t going to cut it for this episode of Looney Tunes, so they turned to slavery, of course. Warner Bros had its own share of racist characters in various scenarios, but the War of Northern Aggression is the backdrop for Bugs Bunny in blackface trying to convince master Yosemite Sam not to beat him. At least for modern viewers, hilarity does not generally ensure.

Mandingo (1975)

To put it simply, Roger Ebert at RogerEbert.com called Mandingo "racist trash." In a post civil rights movement America, critics were perturbed by the lack of sensitivity towards the horror of slavery.

The title of the movie comes from the name for slaves forced to prizefight for their masters' entertainment (think of the scenes from Django Unchained). The premise is a white master and his wife each use their power to pressure/force male and female slaves to have sex with them. It’s depicted more as hot and romantic, which is pretty messed up. Also, all the slaves speak like they’re in a blaxploitation film, which is both confusing and offensive. The movie actually did pretty decently at the box office, but I am not sure who would see it based on this trailer.

Emily Shire is chief researcher for The Week magazine. She has written about pop culture, religion, and women and gender issues at publications including Slate, The Forward, and Jewcy.

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

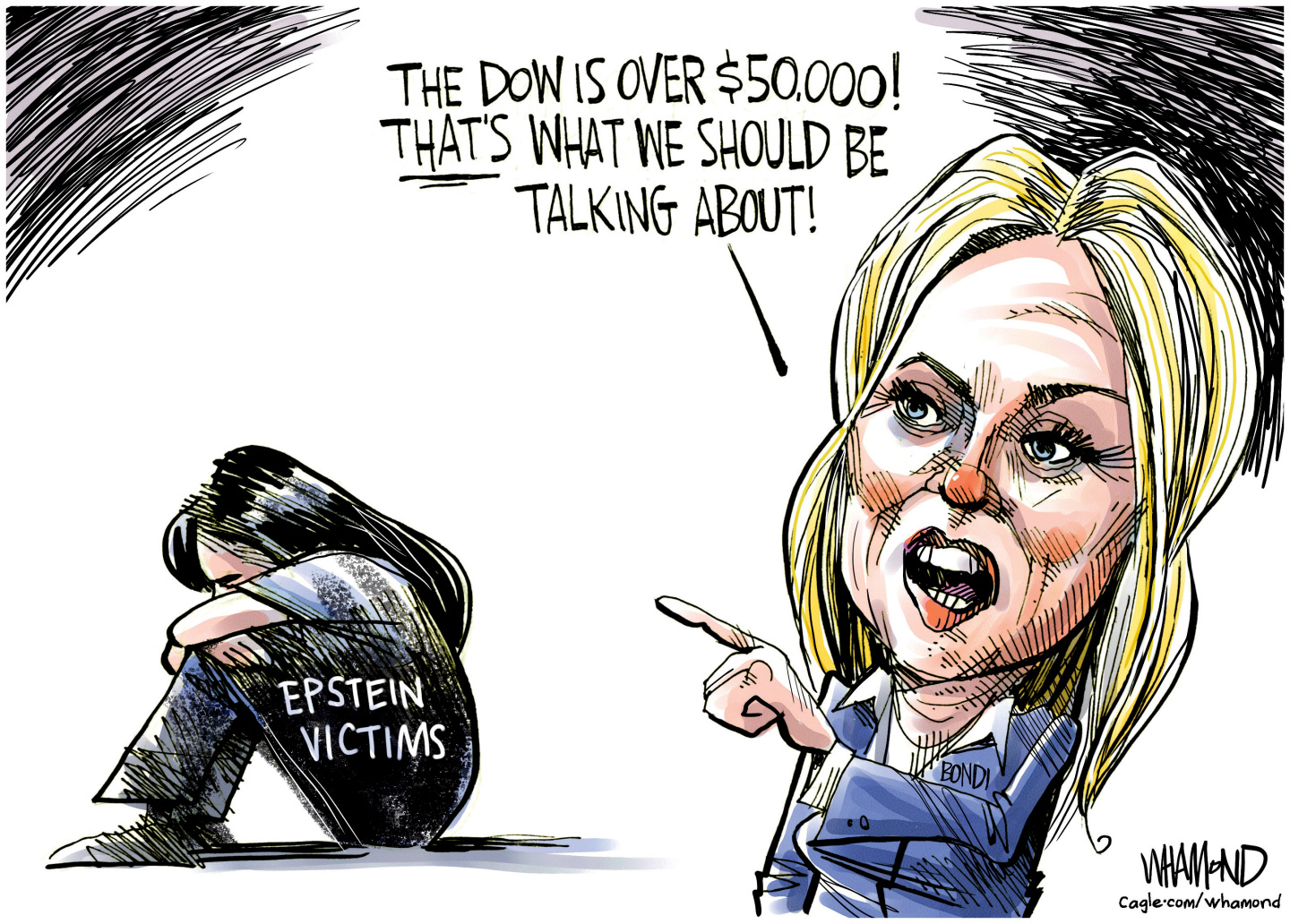

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’