INTERVIEW: The brilliant minds behind Chipotle's haunting scarecrow ad

The behind-the-scenes story of those mechanized crows, that Fiona Apple cover, and more

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Chipotle's latest marketing campaign has gone viral.

The Mexican-themed restaurant chain recently teamed up with Academy Award–winning Moonbot Studios to develop an animated short and iOS game promoting sustainable farming. The three-minute short film went live last week, and quickly made the rounds on Twitter and social media. TheWeek.com's Peter Weber dubbed it "the most beautiful, haunting infomercial you'll ever see," while Slate's Matthew Yglesias and Gawker's Neetzan Zimmerman both called it an "amazing" must-watch.

We rang up Moonbot Studios for a Q&A with Brandon Oldenburg and Limbert Fabian, the short's co-directors, to talk about their inspiration for the film, the production process, what it was like to work with Chipotle, landing Fiona Apple to sing that "Willy Wonka" song, and who almost wound up in the recording booth instead. Here's a (slightly edited) transcript:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

People are really talking about this "Scarecrow" film. What has it been like to watch the response?

BRANDON OLDENBURG: It can be addictive to see the response that something like this has, especially in the first 24 hours. And watching the accelerating rate of change and the amount of people downloading and watching on YouTube... That's pretty awesome.

LIMBERT FABIAN: It's amazing how the dialogue is just incredibly fast. Not only just about the film — that's interesting and we love that — but the subconversation that's going on about the intent of the film.

I know Chipotle really wanted that to happen and we were curious whether it was gonna be very negative or not, but it's definitely spreading the way we thought it would spread as far as the conversations that are being had, whether it be about food, whether it be about the production of the film itself, or, more importantly, the game. Gosh, the response to the game was the biggest question mark. So that's been a lot of fun to watch and see.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Can you talk a little about the project's genesis? What was it like working with Chipotle, and how did the "Cultivate a Better World" idea develop?

FABIAN: They were very clear about what they wanted to say. They were just leaving it up to us to set up how to say it. And that was a lot of fun.

OLDENBURG: Limbert and I — for the past 15 years of our commercial experiences, we've never had a client like this, ever, be so collaborative and so on-point with their notes. Every time they went back to us, saying, "You know, guys, maybe we should change this," it was like, they were so dead-on correct and right... Everybody on this team is like, "This is unheard of."

In all the years in our experience of working in commercial production, we've never seen anything quite like this.

FABIAN: Yeah, we were constantly pinching ourselves.

What kind of notes would they send back to you?

OLDENBURG: At one point — I think in our design of the factory, specifically, we weren't doing it crazy enough. They were like, "You know, these things are more like a Rube Goldberg machine than the way you're thinking about them and they're not that far off from even your wildest interpretation." And after digging further into documentaries and behind-the-scenes footage of food processing and how much energy goes into it, you realize, "Wow, we need to push it even further."

When I was a kid, I always tried to draw the craziest looking science-fiction alien and then my dad would pull out an encyclopedia and show me some sea urchin, and it was crazier than anything you could come up with. And it was based on reality. And that's the thing: Sometimes reality is stranger than fiction.

How many versions of the story did you go through? How did you settle on the scarecrow concept?

OLDENBURG: We went through over 100 and — there were multiple general story synopses, but then once we started to refine one idea, we went through over 100 animatics just to get it as sharp as could before we moved into production.

LINDBERG: Yeah, there were over 100 — oh, gosh, it was almost close to 200 versions of the animatic. I think we topped out at 198 when we submitted the film, as far as cuts of the film. But I think there was a scarecrow before the first animatic.

OLDENBURG: The "Aha!" moment was trying to figure out the antagonist. We were like, "Well, what do scarecrows do?" Well, you know, they scare off, duh, the crows. So it's like, "Well, why are they doing this?" Well, they're protecting the food. And isn't that what a farmer should be doing? Protecting the food, right, 'cause they've gotta get it to market? But are they protecting it, really? And are they allowing the crow to get to the food? And in a way, that's kind of what's happening.

So it's expanding upon that analogy. So there was an "Aha!" moment when we were trying to figure out who the bad guy was and how to define the bad guy, because the bad guy in this very complicated narrative is hard to put a face on. It has more to do with the decision-making of the individuals and those that are part of this gigantic machine.

LINDBERG: There was a time where there was a bad guy. There were these masked scientists that were working behind the scenes — you never saw their faces and they were controlling the machinery, and it just seemed too complex to have another sort of character in our world. We've got the citizens — the consumers — you've got the crows, and you've got the scarecrows. It was like a lightning bolt for us when we were looking at scarecrows and it was like, "Scarecrows, why don't we make them the farmer?" Make them the definition of what the farm is and this idea of farms, and sort of imbue that all onto the scarecrow.

OLDENBURG: There was an "Aha!" moment we also had quite late in the process, as well. We had almost a finished product, but still there was something that wasn't feeling true near the last quarter of the story and it was related to the epiphany for our lead character. There's a moment where he's on the train and he's riding home, and we weren't necessarily doing the epiphany there. He was just seeing and looking out the window with a distant stare and lethargic and introspective and all that. And then he got home and saw a pepper and then it's like, "Well, this doesn't feel right. Why is he doing this today? Why today?" And then when he sees himself as a part of this facade, that was the trigger point.

The scene with the billboard, right?

FABIAN: Yeah, that was totally the missing piece, that billboard. 'Cause for a long time, he was just on the train staring out into the field and sort of analyzing the situation, but without much to do other than sort of go back into himself.

OLDENBURG: It's funny, because even the billboard is the final piece of the billboard is coming together. And for us, that was sort of the locking moment. That was the final piece in the story that goes, "Oh, wait a minute, I've become this thing. I've gotta change something."

Does the scarecrow have a name?

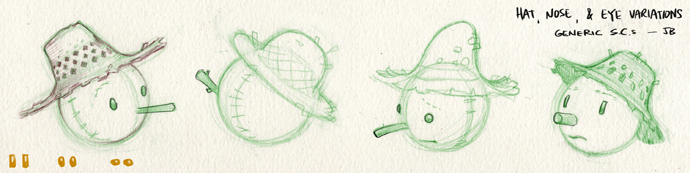

OLDENBURG: For a while we called him "S.C." I know that Chipotle referred to him as Steve.

Besides the billboard scene, what are some of your favorite shots or sequences in the film? That shot of him in the tunnel near the beginning is very dramatic.

OLDENBURG: When I drew that in the storyboard, it was a very subliminal kind of thing that I wanted us to do, which was have it evoke sort of a skull-like shape. I dunno if you noticed that. At the end of the hall, there are two vats with some sort of pink, gelatinous meat-like substance that sort of serve as the eyes; and the other scarecrows, going along way off in the distance, kind of serve as the teeth; and then our scarecrow, in the center, serves as the sinus cavity in the skull. So it all sort of — if you squint your eyes, you can kind of see it.

We were trying to quickly convey what it feels like going into work, you know?

FABIAN: At a job you don't like.

OLDENBURG: We needed to make it feel, right out of the gate, like it was a ritual. It was sort of second nature for him to, like, grab his hammer and swing the rope over his shoulder, and it was all sort of like he was doing it nonchalant. Like he had done it a thousand times before.

How did you come up with the design for the crows? It's clever how they don't flap their wings to fly — they actually turn into little helicopters.

FABIAN: Absolutely. We wanted to strip away any sort of organic reality to them. They're not gonna fly, they're gonna be machines. These guys were emulating birds, right? They look like birds, but they're not birds. [They're these] little helicopters and these little robots that keep the scarecrows moving along. That was a lot fun to do — just, like, "No, they're not gonna fly like regular birds." That'd be a good thing if they flew like regular birds.

OLDENBURG: One of our programmers, she has some experience in building robots, and she's like, "I could totally make one of these if you want, guys. If Chipotle wants one of these, we could make one." It's like a drone, basically.

FABIAN: They're holding out for one.

OLDENBURG: That'd be so cool to eventually make a little drone version of one of those for real.

Let's talk about some of your visual references and influences. I couldn't help but notice there's this Wizard of Oz thing going on at the scarecrow's farm, with the city in the background that looks like the Emerald City. Was that deliberate?

OLDENBURG: The history of cinema is part of our DNA, right? And the things we love just sort of come out naturally. Certain people are starting to make observations about Moonbot — that we have sort of a golden-hued nostalgia. And I guess that's right. I've never been able to put it into words, but there's something about that… keeping one foot in the past, one in the future.

There's new audiences every day and it's kinda cool, specifically for me and my children. I point toward a story that we recently completed called The Numberlys, and my daughter's like, "Why is it black-and-white? Why does it look that way?" Well, there's this director named Fritz Lang and we just really like his film Metropolis, and it's all basically "Metropolis," but for kids now. It's kinda cool to be able to tap into these things that we've forgotten that we love.

But certainly, no one's forgotten about Wizard of Oz. It's sort of blatantly obvious. OK, scarecrow. When was the last time you saw a scarecrow on the screen? Well, Wizard of Oz, probably.

What were some of your other influences? Are there other references or homages that viewers might want to look out for?

OLDENBURG: We chose to do miniatures specifically for his home, which we always related to Miyagi in the sense of — more of an idea than an actual visual reference. His "Miyagi moment" is what we called it.

It's a thing that used to be, and maybe there's a way to reinvent it. And so we chose to do handmade miniatures for that farmhouse, which is his home, with miniature crates and miniature corn stalks and all very organic because they're all real and they're all handmade. Even the fences were hand-whittled and painted in a miniature scale. And there's something really warm and textural about that. It's a nice juxtaposition to the city and all the factory stuff, which is more perfect and sterile.

FABIAN: You need that little extra nudge from the rest of the stuff that was happening. Even though the rest of the world was CG and we worked really hard to make it look dilapidated and worn and used and—

OLDENBURG: And loved and lived in.

FABIAN: And lived in. The farm needed just one more nudge.

Speaking of nostalgia, how did you choose the "Willy Wonka" song?

OLDENBURG: We were referencing a song called "Isn't It Romantic?" And it's been covered by Ella Fitzgerald and other people since, but it originally started in an old film. And we were thinking, "How cool would it be to do a film like that?" Have the irony just sort of be blatant right out of the start, but then by the end, in the third act, it actually becomes true and loses its irony.

That concept stayed true throughout the process of finding this song. It was just a matter of finding the right song that you could have delivered in that way to where it could have a whole new meaning by a key change or a whole new meaning by just slightly changing the orchestration.

I think we had like 40 different tracks we were just throwing up against picture. We tried "Oh, What a Beautiful Morning'" from Oklahoma! and that was kinda cool. And then we were trying even more current pop songs. What was that one song?

FABIAN: Oh, yeah, we had a track by Grizzly Bear which — again, it was working for us for a long time because it had the mechanized sort of thing about factory food production and it was clicking and it opened up in a way that made sense for the reveal of the citizens eating the food. But still something was off.

OLDENBURG: Yeah, and so when we finally came around to "Pure Imagination," you automatically have a connotation, right, for those of us who were around in the '70s or got to see the film in the '80s or whatever? You think immediately to the chocolate factory, but then you go, "Wait a second, this isn't a chocolate factory." It's the opposite of that. So there's an immediate, guttural reaction from a nostalgic sense.

FABIAN: We just went, "Of course." It's like — 'cause you're bringing all that nostalgia back. Your memory of the film. And so it just helped to nudge and move the picture in a way that we all love. Again, speaking to the nostalgia and the tipping our hat to older films and things that we loved as young digesters of good old films.

OLDENBURG: And I think what sealed the deal was the lyric where it says, "Wanna change the world? There's nothing to it." And we were like, "Well, that — that completely matches with the 'cultivate a better world' concept" that we wanna end with.

But again, its more of a motivational speech. It's not necessarily the result of having done something. It's more of like, "You can do this, let's give it a try." And that was important to us for the ending of the film — to end with a pregnant pause with, "Will this work? I dunno, we gotta give it a shot. Let's try."

Did you need permission from the studio to use the song?

OLDENBURG: I think it was Warner Bros., and [Creative Artists Agency] handled all of that.

FABIAN: For a brief second, there was a wacky idea that Gene Wilder might be able to be involved. That was a wacky day — 'cause he's, he's still alive. Put him in the booth and have him sing it!

But you got Fiona Apple to do it.

OLDENBURG: That was the right decision. When we finally got to hear her words — her vocalization up to the track… We all got goose bumps. Took it to a whole new level.

And she recorded it specifically for this project, right?

OLDENBURG: It came down to just finding the right talent, coordinating the schedules and availability, and the window opened and—

FABIAN: That was the wackiest part. There were two hard things that we were up against. We knew that the film was gonna use "Pure Imagination," and we were using that Gene Wilder track for a very long time. And then there was coordinating the right — having her schedule available.

So that was the trickiest thing, was coordinating when she could do a record and get everything put together and then — the one sort of unknown for us was, "Well, we're almost done with the film and we're just kinda waiting to put this piece in and swap out the Gene Wilder track with her version of the song."

That was a little bit of a waiting game. It was the coordination of that pop-star thing.

OLDENBURG: The waiting game on this is another reason why it's all worked out. There's never been a rush to market on this. It was like, "Let's get the story right." And you never hear a client say that. It's like, "There's a deadline and we have to hit it." And they were constantly going, "Let's tweak this one part. Let's make that better."

[It allowed] the story to marinate, and improve with age, and refine with stepping away and being more objective and looking at it again and asking hard questions. "Are we doing the best that we can on this?"

It's a very special, unique client to be able to request that of you.

FABIAN: I think the film was at two minutes at one point and we felt like it needed to get longer and, again, they were just like, "Well, let's do what we have to do."

It was unheard of for us. We had our commercial production hats on.

And even though it's an advertisement, in a way, Chipotle's not even mentioned until the very end.

FABIAN: Yeah, not at all.

OLDENBURG: We were even thinking about, "What sort of vegetable is he gonna put in his hand?" Limbert and I were both hesitant. it was like, "Should we do a pepper? Is that too overt? Should we be more subtle than that?" But we went with it. It felt right.

That's the other major thing in the business. Keep it subtler and go with that sort of punk-rock approach, and it's appreciated.

The interview has been lightly edited and reordered for length and clarity.

All images courtesy of Moonbot Studios.

Sergio Hernandez is business editor of The Week's print edition. He has previously worked for The Daily, ProPublica, the Village Voice, and Gawker.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day