Should apes have legal rights?

The great apes can think, feel, and communicate. Does that mean they should have the same rights as people?

Where did this idea originate?

Twenty years ago, philosophers Peter Singer and Paola Cavalieri published The Great Ape Project, a book that called for chimpanzees, gorillas, bonobos, and orangutans to be accorded the same basic rights as human beings. Since then, a movement has taken root to urge governments and the United Nations to grant legal rights to chimpanzees and other great apes, banning their captivity in zoos and circuses and their use in medical testing for diseases like AIDS or hepatitis. New Zealand extended personhood rights to great apes in 1999, and Spain followed suit in 2008. The U.K., Sweden, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands have also banned research on apes for ethical reasons. While stopping short of a ban, the U.S. government announced this year it would limit funding for medical research to 50 chimpanzees. "I am confident that greatly reducing their use in biomedical research is scientifically sound and the right thing to do," said Francis S. Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health.

Why give rights to apes?

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Activists say that it's now clear that our primate cousins have demonstrated that they have inner lives and relationships, can communicate, and experience emotions. Therefore, they say, we human beings should expand our "moral circle" to include the great apes and protect them from the deliberate infliction of suffering. Apes share up to 98.7 percent of their DNA with humans, notes primatologist Jane Goodall, who says that in a half century of observing chimps she saw many examples of compassion, altruism, calculation, communication, and even some form of conscious thought. "There is no sharp line dividing us from the chimpanzee or from any of the great apes," Goodall says.

Why do the advocates believe apes can think?

The primary evidence offered is the capacity of great apes to learn and use language. The female gorilla Koko, for instance, can make signs for about 1,000 words and understand around 2,000 spoken English words. Scientists at the Great Ape Trust near Des Moines claim that a pair of bonobos there uses language to build sentences, express empathy, and engage in gossip. In the wild, chimps have been observed to use gestures very similar to humans', such as pointing or raising their arms as a way of asking to be picked up. They've also been observed using tools.

Do they have feelings?

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's little doubt that they do. "They show emotions similar to those that we describe in ourselves as happiness, sadness, fear, despair," Goodall said. Chimpanzees become anxious and upset when they are taken away from their families; research also shows that apes feel anger and jealousy when other apes are fed more than they are. They seem capable, too, of recognizing feelings in other apes. When a chimp named Pansy was dying in Scotland in 2010, her family groomed and comforted her as she approached her end. After she died, her best friend Blossom sat by her lifeless body through the night. The other chimps in the enclosure refused to sleep where Patsy died for five days afterward.

What do the skeptics say?

They say that being similar to humans doesn't make apes the same as humans, and question whether sympathetic humans like Goodall are anthropomorphizing — projecting human traits on animals. Steve Jones, professor of genetics at the University of London, points out that even mice share 90 percent of our DNA. "Should they get 90 percent of human rights?" he said. "Where do you stop?" Humans have rights because we live under a moral code, said John D. Morris, an evolutionary creationist. Animals have no understanding of that code. "No ape has any awareness of right or wrong," he said. "If a loose chimp steals a picnic basket in the park, does he go to jail?" The skeptics also say that ending medical research on apes will delay or prevent effective vaccines and treatments and cost human lives. "If we are going to consider closing down AIDS and hepatitis research and giving human rights to chimps," said University of Florida animal psychologist Clive Wynne, "we had better be certain we are not just giving in to a natural but baseless anthropomorphic tendency without solid evidence to back us up."

How solid is the evidence?

It's virtually impossible to prove whether apes are conscious, since neuroscientists still can't agree on how to define consciousness, or how it arises in the human brain. But advocates for ape rights say the fundamental question is not scientific, but moral. We do know for certain that great apes have complex mental abilities, which elevate their capability for suffering. On that basis alone, say rights advocates, apes deserve basic protections from the pain, isolation, and arbitrary imprisonment inflicted by medical experiments or captivity in zoos. "Great apes are thinking, self-aware beings with rich emotional lives," said Peter Singer. "If we regard human rights as something possessed by all human beings, no matter how limited their intellectual or emotional capacities may be, how can we deny similar rights to great apes?"

When chimps retire

Now that the U.S. is retiring most of the chimpanzees it has used for medical testing, they're finally getting their first taste of freedom. The chimps are being moved to animal sanctuaries — most of them to the federally run Chimp Haven in Shreveport, La., which houses over 120 chimps in large social groups in 200 acres of parkland. Some of these chimps have never before been outdoors and are transformed. "A year later, you're not dealing with the same chimp who came here," said caregiver Diane LaBarbera. Earlier this year, 53-year-old Julius made the move after decades in a barren cage at the New Iberia Research Center, getting his first glimpse of the sky since he was captured in Africa as an infant. The freed chimps seem confused at first, then euphoric, said behaviorist Amy Fultz. "They light up. They look up at the sky. To me, they seem to be thinking, 'There's no bars.'"

-

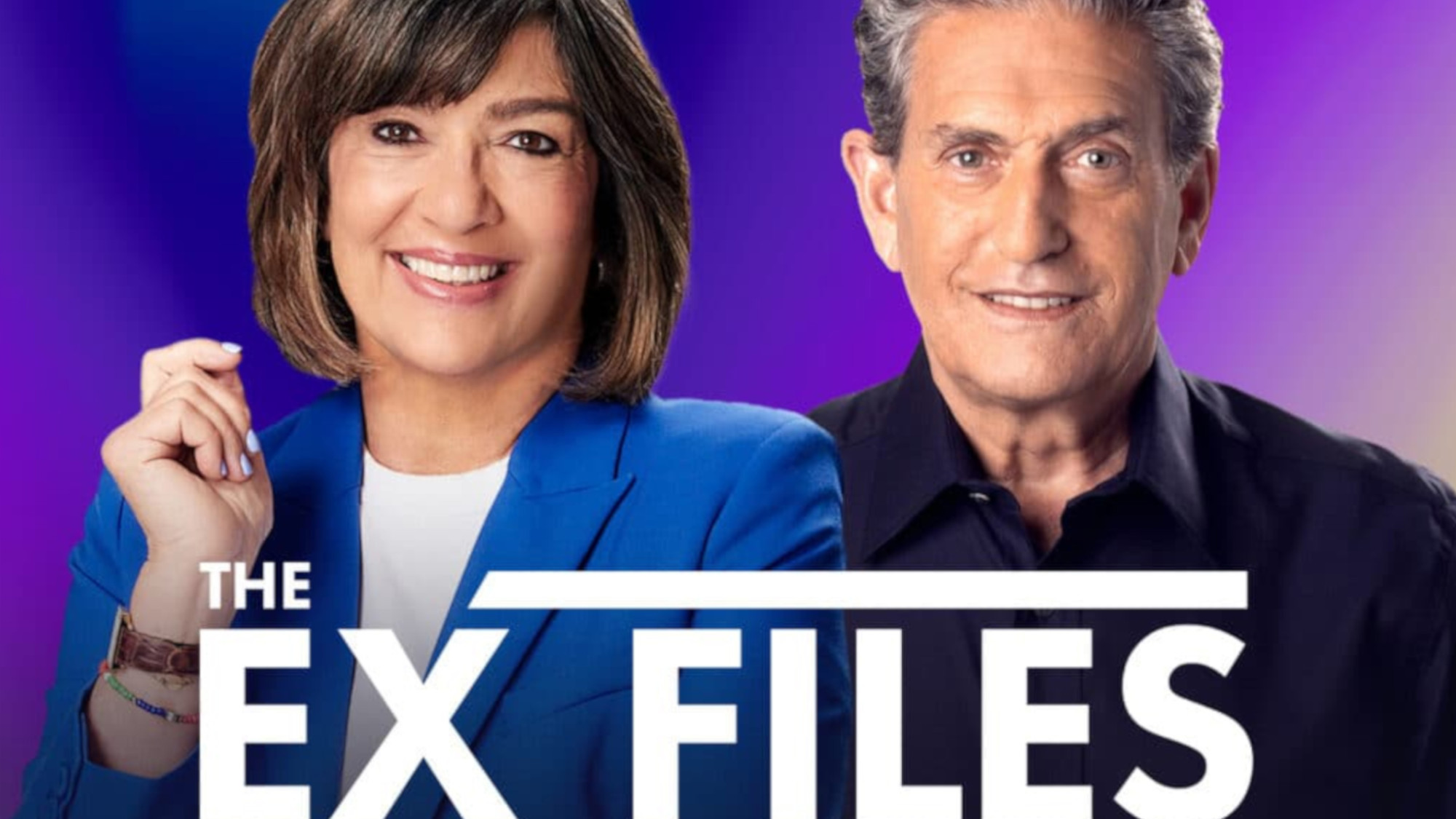

Podcast Reviews: 'The Ex Files' and 'Titanic: Ship of Dreams'

Podcast Reviews: 'The Ex Files' and 'Titanic: Ship of Dreams'Feature An ex-couple start a podcast and a deep dive into why the Titanic sank

-

Critics' choice: Restaurants that write their own rules

Critics' choice: Restaurants that write their own rulesFeature A low-light dining experience, a James Beard Award-winning restaurant, and Hawaiian cuisine with a twist

-

Why is ABC's firing of Terry Moran roiling journalists?

Why is ABC's firing of Terry Moran roiling journalists?Today's Big Question After the network dropped a longtime broadcaster for calling Donald Trump and Stephen Miller 'world-class' haters, some journalists are calling the move chilling