What happens when two ancient galaxies smash into each other?

Imagine an enormous, extraordinarily slow car crash

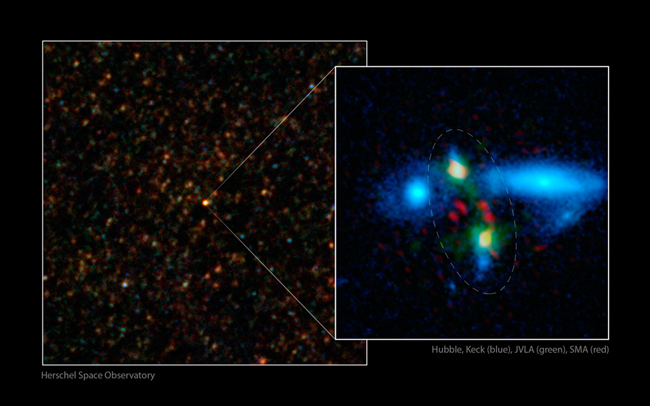

Far across the universe, 11 billion light years away, scientists have discovered two massive galaxies smashing into one another, like an ultra-slow-motion car crash. But the collision isn't happening right now — what we're glimpsing is far in the past. It occurred just 3 billion years after the Big Bang. But because it's so far away, we're just seeing it now.

The two colliding forces are what's known as elliptical galaxies. They don't spin. They don't have outstretched arms like our own Milky Way. Rather, the two star clusters are egg-shaped, violently merging to form a singular, supermassive elliptical galaxy with a combined mass of 400 billion suns.

HXMM01, as the galactic beast is called, likely finished forming 9.5 billion years ago. The merger we're witnessing is creating new stars at a "breakneck speed" of 2,000 suns per year. The Milky Way, for comparison, churns out two new stars annually.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Its discovery is detailed in a new study by Hai Fu, an astronomer at UC Irvine in California, who caught wind of its existence while peering through the European Space Agency's infrared Herschel Space Telescope.

At first, Fu thought the super-luminous blob was an error — a fluke magnified by gravitational lensing, which makes distant objects seem brighter than they really are.

Only it wasn't an error. It was an incredibly lucky find.

HXMM01's discovery could shed light on how supermassive galaxies — like the nearby Messier 87 — form in the first place. Researchers have known that large galaxies often feed on smaller galaxies, kind of like Pac Man, steadily growing larger over hundreds of millions of years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But observing two already-large star formations cramming together to form a singular behemoth could prove to be a study in cosmic efficiency. The next step is to "truly understand what is going on in those galaxies — why the star-formation efficiency is 10 times higher than normal star-forming galaxies," Fu tells Space.com. "That part is a total mystery right now."

-

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?Today’s Big Question Deadly Bondi Beach attack the result of ‘permissive environment’ where warning signs were ‘too often left unchecked’

-

Bulgaria is the latest government to fall amid mass protests

Bulgaria is the latest government to fall amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout

-

Sudoku hard: December 15, 2025

Sudoku hard: December 15, 2025The daily hard sudoku puzzle from The Week