Briefing: The invisible casualties

Is post-traumatic stress disorder something new? As a formal diagnosis, it

A new Rand Corp. study found that one in five Iraq war veterans—up to 300,000 men and women—suffers the flashbacks, depression, and nightmares of post-traumatic stress disorder. Is ther hope for an effective treatment?

Is post-traumatic stress disorder something new?

As a formal diagnosis, it’s fairly recent—but the condition it describes is probably as old as war itself. Back in the Civil War era, returning veterans who were easily startled, quick to anger, and couldn’t find their way in life were said to be suffering from “soldier’s heart.” World War I vets with these symptoms were called “shell-shocked”—reflecting the belief that their nerves had been shattered by constant artillery barrages. World War II vets who withdrew from their families and suddenly flared into violence had “combat fatigue”—although the condition was only whispered about, since it was seen as a character weakness. And the wave of troubled Vietnam vets who turned to drugs or could never recover their footing suffered from “post-Vietnam syndrome.” It wasn’t until 1980 that researchers began referring to the bundle of debilitating symptoms experienced by some war veterans and other survivors as post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What exactly is PTSD?

It’s an anxiety disorder that strikes some people after they have been through a traumatic event. PTSD sufferers, who often experience depression and acute anxiety, are essentially on high alert all the time. In any life-threatening emergency, says University of Southern Mississippi psychologist Raymond Scurfield, “your blood pumps, your heart rate goes up, adrenaline kicks in.” For most people, once the danger has passed, their systems return to normal. But for those with PTSD, the body and mind go into the red zone and stay there. When Stephen Edwards, 40, returned to Willow Glen, Calif., after a tour of duty in Iraq, he found himself constantly reliving an ambush that killed a comrade. “We’d walk into a coffee shop and he’d be looking at the rooftop for snipers,” says his wife, Theresa. After a panic attack left him cowering behind a shopping cart in a grocery store, he enrolled in a PTSD treatment program. Says Edwards: “Every day is a struggle with the depression and the anger.”

Who besides vets does PTSD strike?

Any terrifying event can cause PTSD. The condition, which afflicts an estimated 7.7 million people in the U.S., can hit survivors of rape, assault, fires, natural disasters, and car crashes; it is widespread among people who witnessed or survived the 9/11 terror attacks. But PTSD seems to single out combat survivors—up to 50 percent of combat veterans suffer from PTSD at some point in their lives, according to the Psychiatric Times, compared with 10 percent of hurricane survivors, for example. Experts say Iraq war veterans are particularly vulnerable because of the amorphous nature of that conflict. World War II, for all its bloodshed, had clearly defined front and rear lines; there were places in which soldiers could feel reasonably safe from imminent harm. But life-threatening violence in Iraq is “360/365,” says Iraq veteran Michael Goss. “You feel you are always in danger out there.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Are PTSD’s effects purely psychological?

No. Scientists are beginning to learn how physically devastating PTSD can be. Combat veterans are more likely than the general population to suffer from heart disease, diabetes, strokes, and even cancer. Iraq veterans also run a higher risk of being involved in a car crash: In Iraq, they were trained to gun their vehicles through red lights to thwart sniper attacks, and back home, some can’t shake off the impulse. “My body still thinks it’s in Iraq,” says former infantry scout Jesus Bocanegra.

How long can PTSD last?

In some cases, a lifetime. PTSD may lie dormant for years, only to re-emerge when a sight or sound brings the trauma back to life. Many Vietnam veterans say that televised images of fighting in Iraq have brought their own long-buried memories of war’s horrors to the surface. “I try to stay abreast of the news,” says Hank Vasil, 58, who battled Viet Cong insurgents at close quarters in the late 1960s. “But I reach a point where I have to cut it off.”

Can PTSD be treated?

Yes, but so far with only limited success. Specialists say there is no single course of treatment for the disorder, but they’ve had encouraging results with “combination therapy”—individual and group counseling sessions, antidepressants, and drug and alcohol detox. But it’s a long road back. “There will be problems,” says Robert Shrode, who has struggled to hold down a job and keep his marriage together since returning from Iraq in 2004. “People are going to have to be patient.” Many cases are stubbornly resistant to therapy. Shrode, who lost most of his right arm to a roadside bomb, wonders if he’ll ever feel like himself again. One day not long after he returned from Iraq to his hometown in Kentucky, a passerby casually asked how he was doing. “Buddy,” Shrode shot back, “I’m going to hurt the rest of my life.”

The science of trauma

Our understanding of PTSD has progressed rapidly in recent years, as advances in medical technology—and an unfortunate abundance of large-scale traumas—have given scientists the opportunity to study the brains of Iraq war veterans, 9/11 survivors, and hurricane victims. One of the most promising research findings is that PTSD sufferers have lower-than-average amounts of a hormone called cortisol circulating through their bodies. Cortisol plays an important role in helping the body return to normal functioning after a traumatic event. Researchers are now examining whether raising cortisol levels in PTSD patients would help them dial back from their perpetual state of high alert. Researchers are also finding that environmental factors may play a part in PTSD—people from unstable homes are more likely to develop PTSD than those from stable backgrounds. New research also suggests that PTSD sufferers may be most responsive to intervention right after experiencing a trauma, so new screening techniques are being developed to identify those most at risk. “We don’t walk into trauma equally,” says neuroscientist Rachel Yehuda, “so we don’t all come out of it equally.”

-

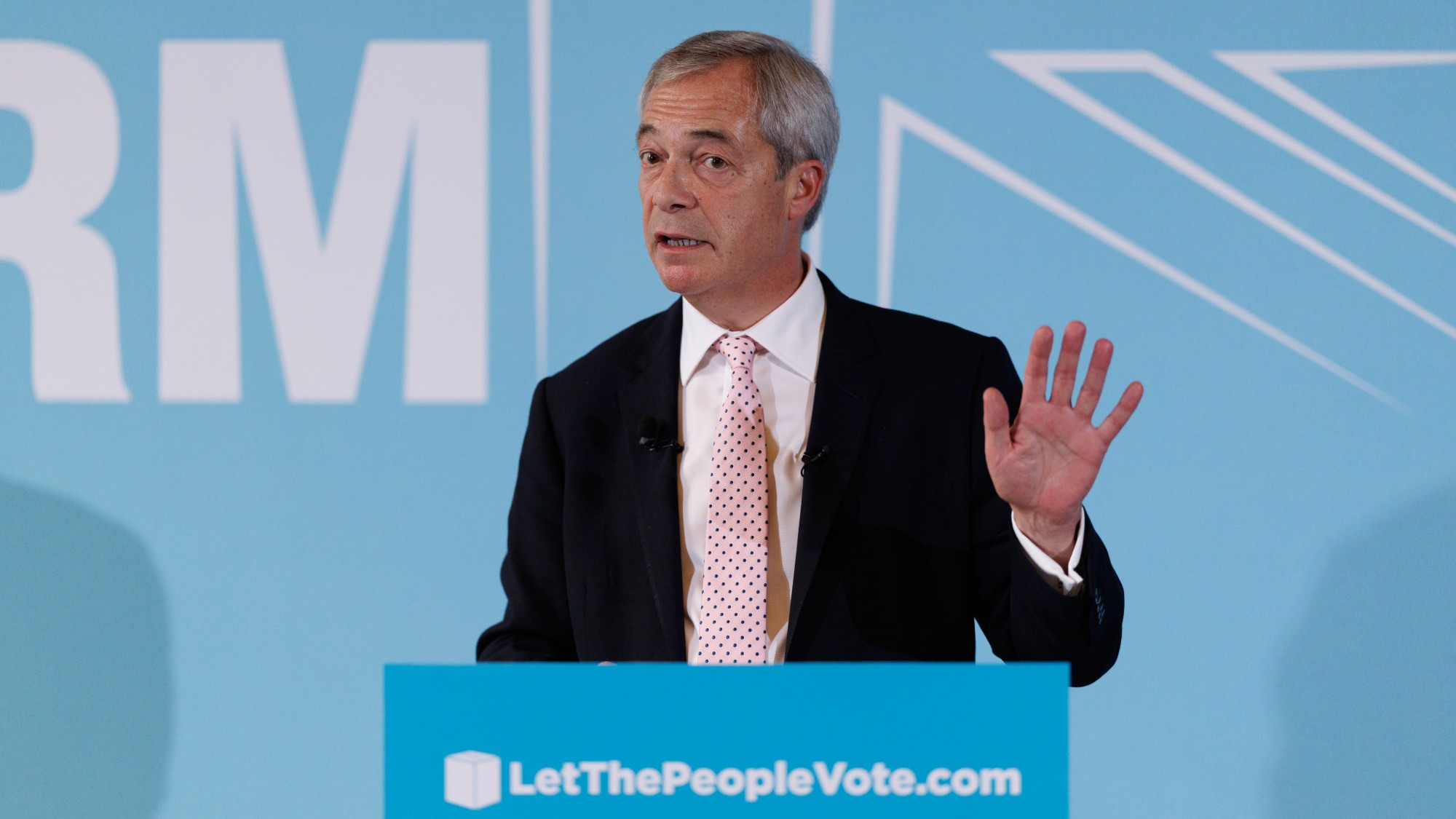

Farage’s £9m windfall: will it smooth his path to power?

Farage’s £9m windfall: will it smooth his path to power?In Depth The record donation has come amidst rumours of collaboration with the Conservatives and allegations of racism in Farage's school days

-

The issue dividing Israel: ultra-Orthodox draft dodgers

The issue dividing Israel: ultra-Orthodox draft dodgersIn the Spotlight A new bill has solidified the community’s ‘draft evasion’ stance, with this issue becoming the country’s ‘greatest internal security threat’

-

Codeword: December 13, 2025

Codeword: December 13, 2025The daily codeword puzzle from The Week