Why the Latino community doesn't need a 'Ferguson moment'

Moments don't bring change. The long slog of progress does.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Earlier this month, Antonio Zambrano-Montes was shot and killed by police in Pasco, Washington. Zambrano-Montes allegedly threw rocks at several officers before running away; video shows three officers firing as he turns to face them. Coming as it did six months after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the Zambrano-Montes case has led to some predictable questions: Is Pasco the next Ferguson? Is this Washington state's Ferguson moment? Is it the Latino Ferguson?

I understand the inclination among media outlets, protesters, and human beings generally to speak in shorthand, seek commonalities, and collapse complex narratives into easily understood similitudes. Our time and column inches are short, and we feel real and justified pressure to grab and hold people's attention. And as a rule, we really want to believe in the power of “moments."

Yet when we frame the news this way we elide far too much — not least the plodding, laborious, and often excruciating nature of change.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

People everywhere hold tightly to the myth of the transformative moment. In the course of the Arab Spring, activists and pundits alike announced that the Arab world was finally bringing an end to despotism — which is exactly what they had proclaimed about Iran a couple of years prior. The war in Ukraine suggests that Russian interest in Eastern Europe didn't end in the moment of the Soviet Union's collapse. And hey, remember Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat at the White House in 1993?

Closer to home, these moments may seem more lasting — Rosa Parks taking a seat, Roe v. Wade, the Matthew Shepard Act — but if we look a little more closely, we'll see much that didn't happen in the days after. We see humanity, untransformed. African-Americans still systematically confronted by entrenched, institutional racism; women's lives shattered by legal restrictions on personal health care decisions; children living in fear that their classmates (or family) might discover their sexuality.

No single event, no matter how painful or paradigm-shifting, will ever change history or humanity. It won't undo and uproot the lived experiences, long-held expectations, ignorance, or folly of every life touched by that event.

On the contrary, as the world has seen in Egypt, Ukraine, and Missouri, efforts to shift the paradigm lead many to cleave to the status quo — from elected officials, to college professors, to old friends around whom you suddenly can't discuss the news.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We see the same in our institutions, bureaucracies that both enable society to function and bury us in legalese and minutia. We also see it in culture, that intangible and enigmatic thing, forged in every moment of every day, along and across the lines that both bind and divide us.

Moreover, neither Brown nor the town of Ferguson may be reduced to the symbols they have been pressed into being. People actually live in Ferguson, people whose lives have been daily shaped by the realities that Michael Brown's killing brought to light. And much as we have a nationwide problem with police brutality and systemic racism in many forms, much as the killing of Antonio Zambrano-Montes may look like the killing of Michael Brown (and Eric Garner and Rekia Boyd and Jessie Hernandez and Aiyana Jones and Oscar Grant and Tamir Rice and…), at the end of the day these are all individuals, with individual stories. We do them a disservice when we collapse them into one big heap of National Controversy.

Finally, transformation is hard, long work. Rosa Parks was a grassroots leader who trained for that day on the bus, and she remained a community activist for the rest of her life. Egyptian and Iranian reformists have a history that goes back decades, and they face jail and torture today. The people who protested in Missouri last August continue their advocacy, continue to uncover and fight injustice, and the Latino community of Washington state is tackling a whole range of issues unlikely to be resolved quickly or easily.

We must find a way to write, talk, and remember these events without short-changing their complexity. Even as we seek parallels and make connections, we must respect individual stories and widely divergent community experiences. Whether we're reporting the news or responding to it, we must find a way to ground our discourse in context and history, and give the long haul its due.

To do otherwise is to turn tragedy into boilerplate, and risk exhausting the emotions and energies of the very people whose stories we mean to serve. There are no “moments." Transformation is a process — and a long one at that.

Emily L. Hauser is a long-time commentary writer. Her work has appeared in a variety of outlets, including The Daily Beast, Haaretz, The Forward, Chicago Tribune, and The Dallas Morning News, where she has looked at a wide range of topics, from helmet laws to forgetfulness to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straits

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in the remote Danish protectorate shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

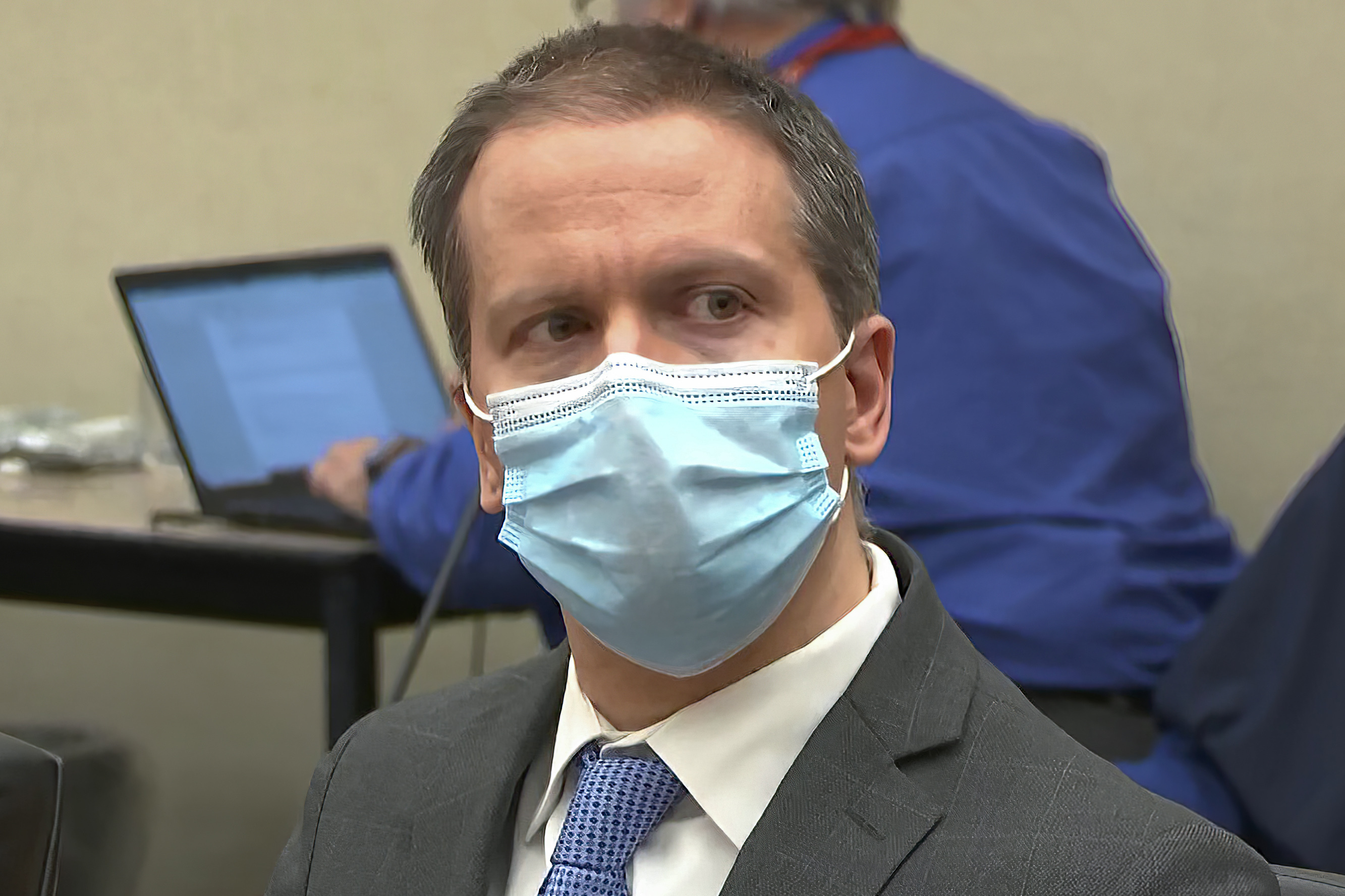

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read