In praise of the land value tax

An unexpected lesson of Ben's Chili Bowl

Ben's Chili Bowl is a staple here in the District of Columbia. Established in 1958 by a local African-American family that still runs the joint, its heartburn-inducing half-smoke chili dogs have survived segregation, social upheaval, riots, and gentrification.

In 2008, the business expanded to the building next door. And a few months from now, another Chili Bowl should open in D.C.'s northeastern quadrant.

How did Ben's not only survive, but thrive? Over at The Washington Post, Emily Badger has a retrospective that teases out two key factors: First, Ben's adapted over the years to new clientele with different cultural tastes, by banning smoking in the restaurant and adding veggie dogs to the menu, for example. There's a kind of cultural innovation involved here; knowing which aspects of the business to sacrifice and which to preserve, and how to open up to new customers without alienating old ones.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The second thing Ben's Chili Bowl did was own its buildings, which gave the business more control over its fate and removed fear of precipitous rent hikes. All of which made the long-term planning, renovations, and expansions more doable.

Ben's Chili Bowl is flourishing. And it flies in the face of two common frustrations with businesses today. First, the frustration with big, sclerotic businesses that aren't pushed to adapt and update. And second, the lamentation that we no longer have businesses that operate with an ethos of rootedness — whose behavior is guided by the knowledge that they're part of a larger communal fabric from a particular place and with a particular rhythm and identity.

How can we encourage more nimble-but-rooted businesses like Ben's? Here's one thought: Pass a national land value tax.

I know what you're thinking: "How the hell is another tax going to help?" But bear with me for a moment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The key thing to realize about a land value tax (or LVT for short) is that nothing you do can affect it. If you build something new on the lot or improve some already existing structure, that doesn't raise the LVT, as it would with a property tax. If you make more money doing whatever you do with the land, that doesn't raise the LVT either, as it would with an income tax.

This is why economists love it. By definition, an LVT only captures "rent" — in economics-speak, income you earn by happenstance or luck rather than by actually creating new wealth.

Your tax burden under an LVT goes up only if the value of the land itself — the one thing you have no control over — also goes up. And the way the value of the land goes up is if the local economy becomes more vibrant and productive and thus a place more people want to live and work in. If you own a business, that increased vibrancy will bring you new sales and income, allowing you to keep up with the increased LVT payments. If you're a landlord, that vibrancy will naturally allow you to charge people more to live in your building. There will of course be marginal cases where businesses that would survive without the LVT get killed by its existence. But on the whole, the tax's burden is naturally anchored to the productivity of the local economy.

The other crucial thing about an LVT is it makes all that good behavior we listed above more likely. If you've got valuable land, it's not as profitable to just sit on it and wait to make a killing, or to just jack up rents and get fat off the proceeds while you sit on your thumbs. You've got an incentive to either invest in the land or the business you own on the land; improve it, create something new on it, hire more people to work, etc.

That would help fight economic blight in abandoned urban centers, and nudge developers to build more housing to alleviate the housing crisis. It would also discourage land hoarding, since it makes it less attractive to own land unless you've actually got something productive to do with it. That, in turn, would make land ownership a bit more distributed, encouraging small and local businesses like Ben's Chili Bowl that actually own their plot. And that would help fight inequality, since the increasing value of land looks to be the key driver of the rising wealth inequality documented by Thomas Piketty.

The LVT isn't a panacea. It could put something of a ceiling on inequality, but we'd still need to raise the floor. Ben's Chili Bowl survived gentrification — which is basically people with little purchasing power getting pushed out by people with more purchasing power — but many other business aren't so lucky. The LVT would discourage landowners from just sitting around and waiting to get rich off gentrification. But we'd also need to raise the purchasing power of the people already in any given neighborhood, so that bringing vibrancy to the area doesn't require their displacement, and so they can supply the raw demand that will allow more Ben's Chili Bowls to arise.

If the revenue from any tax deserves to get pumped into a more generous and expansive social safety net, it's the revenue from a land value tax. By all accounts, an LVT could raise massive amounts of revenue, and yes, we should definitely think about using some of that bounty as an excuse to roll back or adjust property, income, and businesses taxes. But a lot of that revenue ought to go to things like more food stamps and more unemployment insurance and more Medicaid and a universal child allowance — or even a universal basic income.

The meritorious individual, and the idea that particular instances of wealth creation can easily be attributed to particular acts and people, is one of the great superstitions of American capitalism. The cool thing about an LVT is it really reveals how an economy is really an ecology. Everything is interconnected, no man is an island, and no single act of productivity can truly be carved out from the cooperative whole. No one can create more land and no can make land itself intrinsically better, so when the value of land rises, that is literally an ecological phenomenon. In truth, a sizeable portion of the wealth our economy creates really does belong to no one and everyone at the same time.

Unfortunately, that also means we'll need to kill that superstitition before a land value tax — or lots of other worthwhile policies — will have any real chance of passing.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

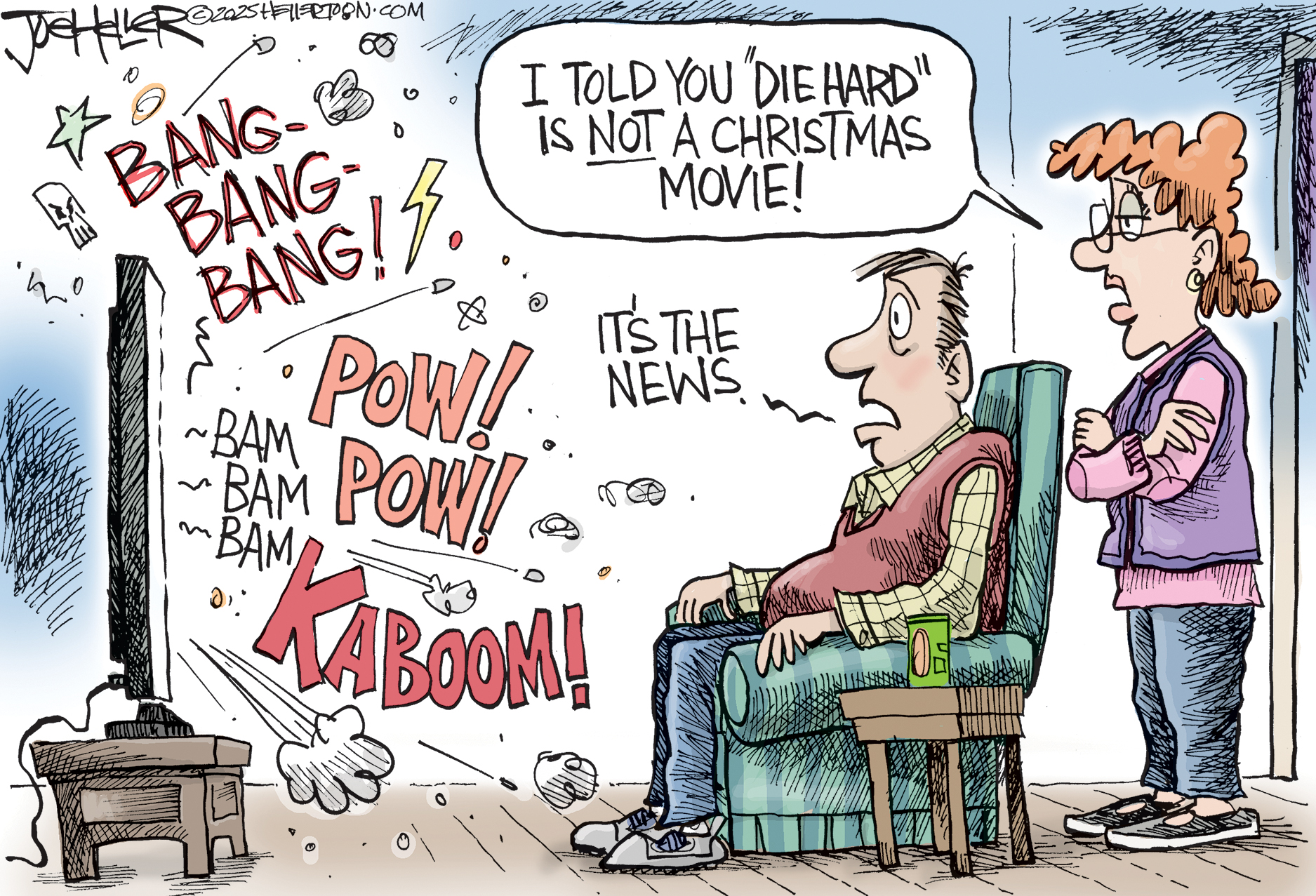

Political cartoons for December 21

Political cartoons for December 21Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Christmas movies, AI sermons, and more

-

A luxury walking tour in Western Australia

A luxury walking tour in Western AustraliaThe Week Recommends Walk through an ‘ancient forest’ and listen to the ‘gentle hushing’ of the upper canopy

-

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers want

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers wantThe Explainer White supremacism has a new face in the US: a clean-cut 27-year-old with a vast social media following