President Obama says climate change is a national security threat. Too bad he doesn't act like it.

Obama wants to appear tough-minded and realistic. He's failing on both counts.

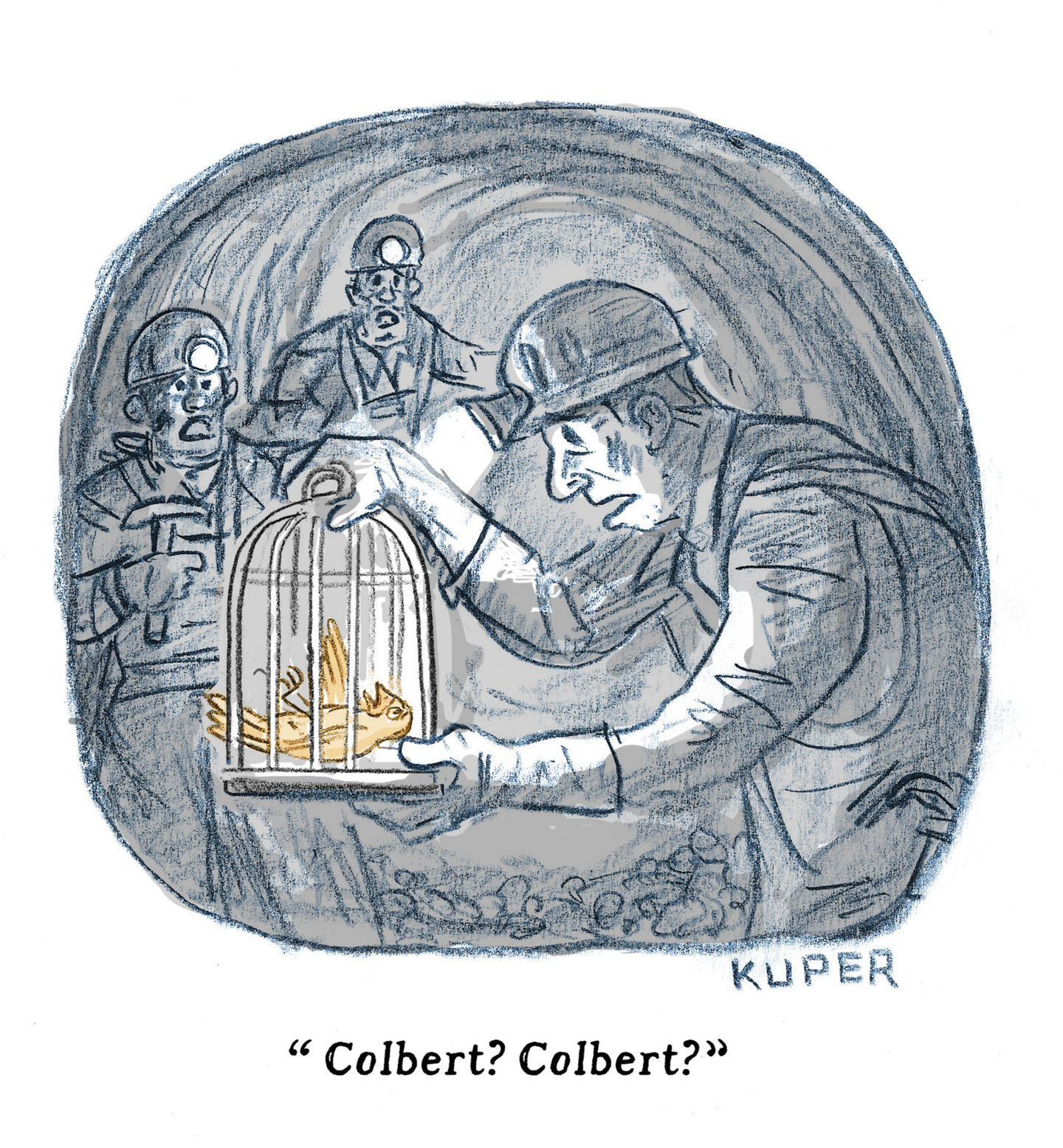

President Obama, in his Dr. Jekyll mode when it comes to climate change, has been advancing one of my favorite arguments on the issue: that it is a threat to national security. This isn't so much strictly true — our armed forces or cities are not under enemy fire — as a good way of shaking people out of the common idea that climate change is some marginal environmentalist issue. On the contrary, it's up there with the economy in importance.

As Greg Sargent reports, Obama brought up the idea in a speech yesterday before a graduating class of Coast Guard cadets, saying that the "urgent need to combat and adapt to climate change" would shape their whole careers. He's definitely right about that!

But the problem with his framing is that it does not remotely square with his actions. Only a few days ago Mr. Hyde emerged, with the Obama administration announcing preliminary approval for Shell to drill for oil in the Arctic Ocean off of Alaska. If we treated climate change as an actual security threat, that is not the kind of policy we would approve.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

McKenzie Funk, who wrote a long, riveting piece detailing how Shell wrecked an exploratory drilling rig in the Arctic in 2012, has an interesting follow-up article explaining how Shell's team of futurists think about climate change and oil:

They were based on what Bentham called "three hard truths": That energy demand, thanks in part to booming China and India, would only rise; that supply would struggle to keep up; and that climate change was dangerously real. Shell’s internal research showed that alternative energy systems — wind, solar, carbon capture — would take decades to make just a 1-percent dent in our massive global energy system, even if they grew at 25 percent a year. [New York Times Magazine]

This is almost certainly how Obama views the issue. Climate change is real, but energy demand is inescapable, and renewables just can't scale up fast enough to meet the demand. Therefore, if any previously frozen place in the Arctic melts, we better extract what carbon we can out of there.

It sounds tough-minded and realistic. It isn't. The only immovable part of the above equation is climate change, insofar as it is driven by the laws of physics and the quantities of greenhouse gases that have already been emitted. Everything else — from the rate of renewable installation, to the level of energy demand, to the future emissions path — can be changed with policy.

What's more, if you assume that no serious climate policy will be implemented, that the only way to decarbonize energy is to sit back and hope the price of solar panels continues to plummet, and that energy demand is utterly inflexible, then you are building catastrophic damage into your premises. Uncontrolled climate change, especially post-2100, could completely wreck much of human society.

Those assumptions are precisely the kind that are tossed over the side when war is declared. In full wartime mobilization, it would be rank defeatism to say something like, "Even if we scale up tank production by 25 percent a year, it'll take us decades to catch up with the enemy." Instead, the only question that matters is: "How do we wring the absolute maximum amount of materiel out of our stock of resources, capital, and labor?"

My favorite example of what this means practically can be found in Marc Reisner's classic book on the history of water in the American West. It concerns Grand Coulee Dam, which was just being completed when World War II broke out:

As the first six generators were being installed, the next two units were still being manufactured and wouldn't be ready for power production for some weeks. The war was at such a critical juncture that some weeks was too long. The Bureau [of Reclamation] collected every outsize piece of transportation equipment it could find, took the two generators waiting to be installed at Shasta Dam, and laboriously moved them to Grand Coulee instead. Shasta's generators were thirty thousand kilowatts smaller than Grand Coulee's and the turbines revolved in the wrong direction: Grand Coulee's went clockwise, Shasta's went counterclockwise. The Bureau solved the problem by installing the Shasta units in the wrong pits and excavating tunnels to the proper ones next door, so the water could surge in from the right side. After the war, the engineers had to invent some mammoth excavation devices to shoehorn them out. [Cadillac Desert]

Enormous quantities of electric power — to this day Grand Coulee is the single largest power plant in the nation — enabled enormous smelting of bauxite into aluminum. That, in turn, allowed America to beat the world at airplane production.

If we really considered climate change a national security emergency (which it is), that's how we would be thinking. We would drop the faux-realistic, Very Serious Person estimates of how things are likely to proceed if we rule out all changes but piddling ones, and get down to what is and is not physically possible.

It turns out that there are worked-out models of a crash decarbonization comparable in vigor to a war effort. There's no way to know for sure if they'll work — but the only way to find out is to try.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

5 low ratings cartoons about the Late Show cancellation

5 low ratings cartoons about the Late Show cancellationCartoons Artists take on early warning signs, the Gen Z stare, and more

-

Connie Francis: Superstar of the early 1960s pop scene

Connie Francis: Superstar of the early 1960s pop sceneIn the Spotlight The 'Pretty Little Baby' and 'Stupid Cupid' singer has died aged 87

-

Crossword: July 26, 2025

Crossword: July 26, 2025The Week's daily crossword puzzle

-

Dozens killed as heavy rains cause landslides, flooding in Indonesia

Dozens killed as heavy rains cause landslides, flooding in IndonesiaSpeed Read

-

At least 4 dead in Nashville floods after 7 inches of rain douse area

At least 4 dead in Nashville floods after 7 inches of rain douse areaSpeed Read

-

At least 111 Texans died from February winter storm, mostly due to hypothermia, state says

At least 111 Texans died from February winter storm, mostly due to hypothermia, state saysSpeed Read

-

9 dead, 140 missing after glacier breaks and triggers flooding in India

9 dead, 140 missing after glacier breaks and triggers flooding in IndiaSpeed Read

-

Family-owned winery among properties destroyed by raging fire in Napa Valley

Family-owned winery among properties destroyed by raging fire in Napa ValleySpeed Read

-

West Coast fires: Death toll reaches 33 as states deal with poor air quality

West Coast fires: Death toll reaches 33 as states deal with poor air qualitySpeed Read

-

All national forests in California temporarily closed due to fire danger

All national forests in California temporarily closed due to fire dangerSpeed Read

-

Fox News fires anchor Ed Henry over sexual misconduct complaint

Fox News fires anchor Ed Henry over sexual misconduct complaintSpeed Read