What the internet forgets about the Magna Carta

It was defined by the nobility, not the people

It's been a good run. After 800 years, the Magna Carta era is over.

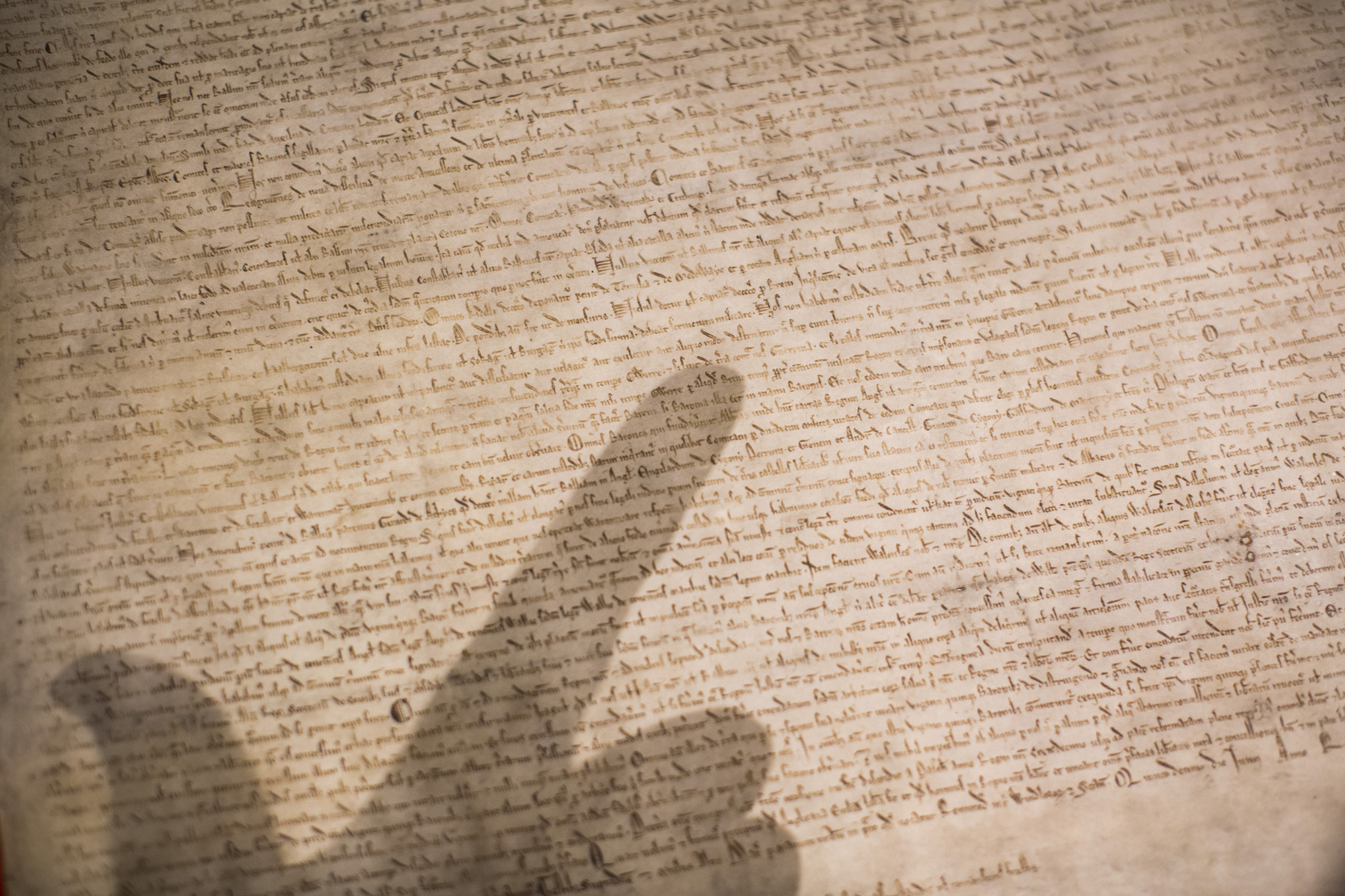

The bias of the times just runs against the document that a group of nobles forced King John to sign in 1215, limiting the power of the monarchy. Like the Declaration of Independence itself, the more we think about it, the more the Magna Carta makes us uncomfortable about the source of liberty.

That hasn't stopped some idealists from trying to resurrect it, though. Plucky Scots concerned their online rights are slipping away have called for their government to create "the first digital Magna Carta" — although the original, of course, was forced on the state, not solicited from it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Meanwhile the British Library, poignantly impressed that the old charter's octocentenary "coincided with the 25th anniversary of the world wide web," solicited a public vote "on 500 clauses submitted by 3,000 young people to create a new Magna Carta, or great charter, for the digital age," as Mashable reported. Of the top 10 choices, four explicitly oppose censorship, two demand freedom of speech, and three would require equal access to the internet. A festival of rights, yes — but a Magna Carta it's not.

The Magna Carta wasn't about universal rights. True, the charter affirmed the idea that unless the power of the state is limited, anyone's liberty is merely a plaything. But that's just a conceptual cherry on top. What the Magna Carta really indicates is that all the abstraction and principle in the world won't get you liberty unless nobles get it for you.

Uh oh.

Public opinion, meet the unthinkable. From Runnymeade right up to the Declaration, it was powerful, privileged elites who staked out our foundational liberties, imposing them on the governing power.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Given how limited, partial, and unequal those liberties have been throughout so much of our history, it's perfectly understandable that our democratic spirit rebels against the thought of owing our cherished freedoms to cliques of dead aristocrats. We hate the idea of being stuck with a past we don't honor. And we despise the idea that we can't really have freedoms without liberty, a.k.a political freedom from the rule of a master.

But we also know, deep down, that the state is the only thing really holding us together. Public opinion is pretty much certain that Hobbes was right: Absent a single, all-powerful interpreter, we'll go off the rails as quickly as the Israelites who wound up worshipping a golden calf as soon as Moses took a hilltop hiatus.

The powerful, naturally, don't buy that at all. They know from experience: If you're brilliant, courageous, magnanimous, and independent enough, you don't need a Moses. Hobbes quietly concedes that such people — the nobility of the past — can't be spooked into embracing an all-powerful master.

And that's why any "online Magna Carta" is an oxymoron. Without the Zuckerbergs and Bezoses of the world storming the White House, it'll be a list of pleadings drawn up by people too weak — even in numbers — to truly challenge the regime's control.

There's no better reminder that the internet isn't what used to be called a "polity."

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels