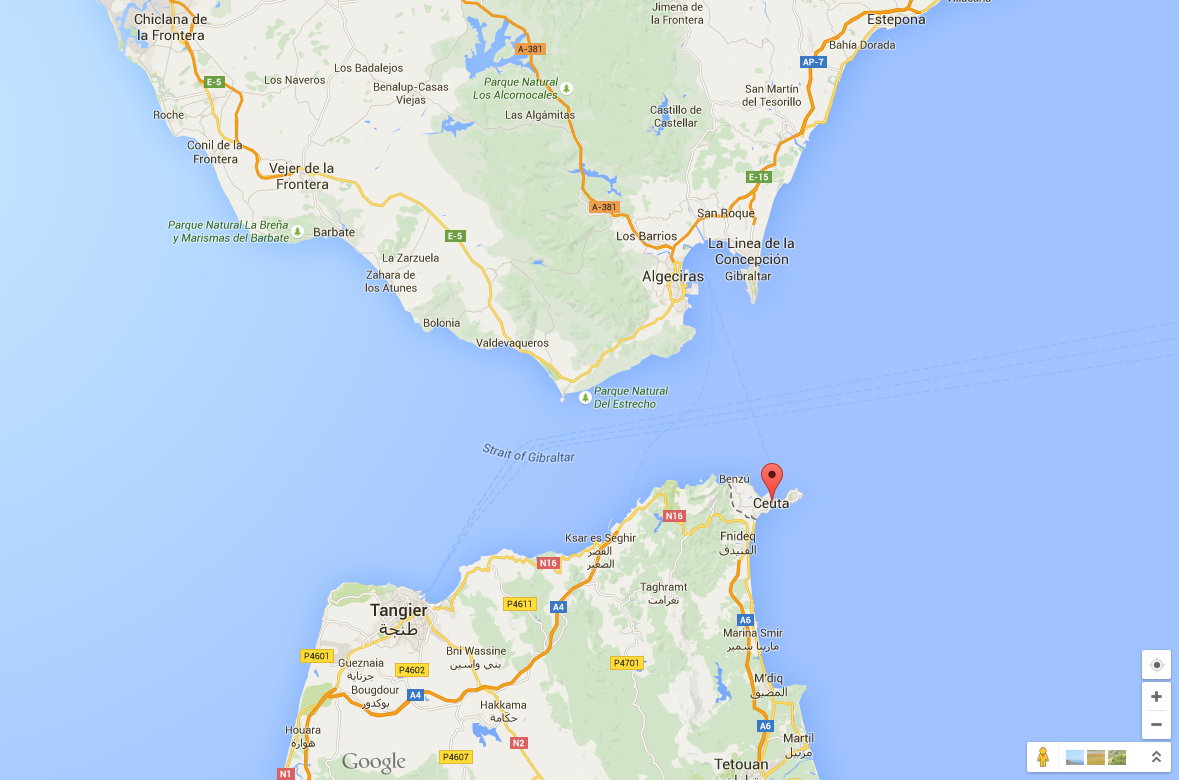

This Spanish city in Africa has become hugely symbolic of Europe's migrant crisis

Life on the land border between Africa and Europe

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

CEUTA, Spain — I'd been warned there would be mobs of people flooding the border, each clamoring for their chance to earn a day's wage in euros. "It gets ugly there," an expat living in a nearby town told me. "They can make 200 dirham a day [equivalent to $20] in Ceuta. Where else can you earn $20 a day in this country?"

When I reached the border between Morocco and Ceuta — which is on the African continent but still a part of Spain — things were busy, though the morning rush had clearly subsided. Much of the Moroccan side of the border looked like a bad party that had ended early. Dozens of listless people stood around, seemingly unsure of what to do or where to go.

Still, a steady line of foreigners streamed through the border checkpoint. They were mostly women, wearing veils and carrying oversized packs. Many shared the resigned features of someone simply going through the motions.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

These border-crossers were some of the few Africans who can legally work in Ceuta, and this was their daily commute — not idling on some clogged highway or squeezed into an over-packed subway car, but simply waiting their turn to walk the few hundred feet separating Africa from Europe, where they could make far more money than they could in Morocco.

Seized by the Portuguese in 1415 and formally handed over to Spain 250 years later, Ceuta is one of only two land borders between Africa and the EU. As a result, this seven-square-mile peninsula outpost occupies some of the most sought-after real estate on the entire African continent.

For a region buckling under the pressure of the largest humanitarian crisis since World War II — almost 60 million displaced people worldwide, according to the United Nations — Ceuta is seen by many migrants as a secret backdoor to stability and sanctuary.

At least, it was for a while.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Last year, Ceuta's twin enclave Melilla — another town attached to Morocco but technically a part of Spain — became internet famous when photos were published of dozens of migrants attempting to scale the city's razor-wire fences. The pictures — with a ring of men perched on a fence encircling a plush green golf course — seemed like something from a dystopian sci-fi film, not uber-civilized, modern-day Europe.

The migrants were soon captured and returned to Morocco. In a video of the event, many of the men were shown being hit with batons as they were forcefully pulled off the fence.

Since then, the EU has taken extra measures to rope these two Spanish cities off from the rest of the African continent. "They have a new electrified fence surrounding the whole place," a hotel owner in a Moroccan border town told me when asked about refugees trying to enter Ceuta. "And it's turned on."

Ceuta and Melilla have become something of a microcosm of the Europe-Africa migrant crisis. Ceuta is a constant target for Africans trying to enter the EU illegally. Thousands of young men travel from all over the continent, many camping for months in the hills surrounding the city, for the chance to scale Ceuta's razor-wire walls.

You can see in miniature in Ceuta all of Africa's massive humanitarian and economic challenges, along with the EU's growing anti-immigrant mentality. As NPR put it earlier this year:

Along with its sister city Melilla, this ancient Mediterranean outpost has contributed more recruits to the self-declared Islamic State per capita than any other town in Europe.You'd never know it though, mingling with tourists wowed by Ceuta's medieval fortress walls and white sand beaches.But this is a city that's deeply divided. About half of its 80,000 people are more prosperous Europeans, and half are Arabic-speaking Muslims disproportionately plagued by poverty. [NPR]

Downtown Ceuta is a speedy 15-minute bus ride from the chain-linked demarcation line, but it might as well be a million miles away. Separated from the Moroccans and eager migrants to the west, Ceuta's often-wealthy residents are celebrating 600 years of European control of the city.

When I visited, around 100 people stood outside the Church of Santa Maria of Africa, shaded by swaying palm trees. Inside, a cross section of the peninsula's citizens were lined up to pay homage to the Shrine of Our Lady of Africa — the most revered religious icon in the city.

This annual tradition was the culmination of a multi-day celebration observed exclusively in Ceuta. The statue, in essence, commemorates the moment Portugal captured the city from the Muslim kingdoms that had governed the area for the previous 700 years.

Once claimed by Portugal, this church was the last Catholic site before European ships shed the calm waters of the Mediterranean for the unknown of the vast Atlantic Ocean.

Today, Ceuta is still an important port. But rather than an exit for seafarers, it's become a beacon for thousands of desperate people attempting to get to Europe somehow, some way. Despite its name, however, the Shrine of Our Lady of Africa is not exactly a welcome sign for would-be visitors fleeing African lands.

The faithful inside the church — many of them Ceuta residents for multiple generations — seem aware of the troubled waters around them, thankful and relaxed behind the fences separating them from the rest of the continent.

"It's our home," one of the churchgoers said, looking around confidently at the gathered group. "Mi casa."

Back at the border at the end of the day, I walked with the migrant workers as far as I could. As we approached the station, the women quietly proceeded to a small holding area. They marched over without being prompted where to go. As I looked back, they neither frowned nor smiled. They weren't going from Europe to Africa, not really. It was clear this was just another part of their commute.

Micah Spangler is a freelance writer based in Washington, DC. His work has appeared in CNN, The Daily Beast, VICE, Maxim, and Yahoo Travel, among others. For more from Micah, follow him on Twitter.