My teenage sons are the smartest people I know. And sometimes the dumbest, too.

Teenagers prove you can know everything and nothing all at once

Teenagers fool us with their size, vocabulary, and swift mastery of new devices. They seem to be about the right shape to fit into the adult world. They drive cars. They know algebra. So it's always momentarily shocking to find out that they don't know how to address an envelope or operate a can opener.

My kids are the only people in my house who are as smart as my smart TV. I honestly have to enlist their help every time I want to change the channel. They know how to work Netflix, and they can figure out how to get WiFi anywhere in the world. And yet…

My son recently started a road trip by quickly clicking an address on his phone's GPS. He then drove to the exact right address in the wrong state. It's these little things that you'd never think to explain that turn out to be big things. When he was leaving, should I have added "Go to the right state!" to my standard "Make good choices!"?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

My teenagers know Pi to 20 decimal places, but they do not understand why keys matter. Their house keys are used and discarded like tissues. I sat dumbfounded as my husband explained to them the etymology of the word "key." The reason people refer to the most important part as the "key" part is that keys are really important. Seriously, I wondered, does this even need to be said? How could a person with the motor skills to operate a key not know this?

They know all the elements on the periodic table. They can name every starting player for every team in the NBA. But they were surprised to learn that chicken, left on the counter overnight, goes bad. At some point, facts like this become a matter of survival.

Of course some of this is just the teenage brain, designed like a sieve and with an incomplete prefrontal cortex. But it's also just a lack of information. Their defense is simple and consistent: "I didn't know that was a thing." That explanation should find its way into a scientific journal.

I didn't know that was a thing. This phrase echoes in my mind, bringing me back to those hazy, soupy teen years when I could only see a few feet ahead of myself. My parents probably shook their heads a lot, but they didn't try to spoon feed me facts. No one waved from the bus stop shouting, "Have a good day! Don't drink water from a still pond! Run in a zig zag if a bear chases you!" Everything I know I learned from cartoons or calamity.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There are a million things I never knew were a thing. When I was 19, I bought a used Volkswagen for $500. At the time I knew a lot about French literature and pretty much everything about William Faulkner. But I didn't know you needed to put oil in a car. No one had ever told me, so I didn't know that was a thing.

That same year I backpacked all over Europe with my passport in my back pocket. Now that I think of it, passports could be described as "key." I didn't know that was a thing either.

I can work myself into a panic thinking of all the things that my kids probably don't know. Don't drink soda and eat pop rocks, or your head will explode. Never put your drink down at a bar. A person who has to say "to be honest" isn't going to be. If you see the shoreline rise rapidly, run!

This must be why parents just stick to the basics: Look both ways before crossing the street, wash your hands, don't let the bedbugs bite. The rest of it is going to be filled in along the way, an education provided not by us, but by a series of small catastrophes that they'll likely survive.

Annabel Monaghan is a lifestyle columnist at The Week and the author of Does This Volvo Make My Butt Look Big? (2016), a collection of essays for moms and other tired people. She is also the author of two novels for young adults, A Girl Named Digit (2012) and Double Digit (2014), and the co-author of Click! The Girls Guide to Knowing What You Want and Making it Happen (2007). She lives in Rye, New York, with her husband and three sons. Visit her at www.annabelmonaghan.com.

-

Digital addiction: the compulsion to stay online

Digital addiction: the compulsion to stay onlineIn depth What it is and how to stop it

-

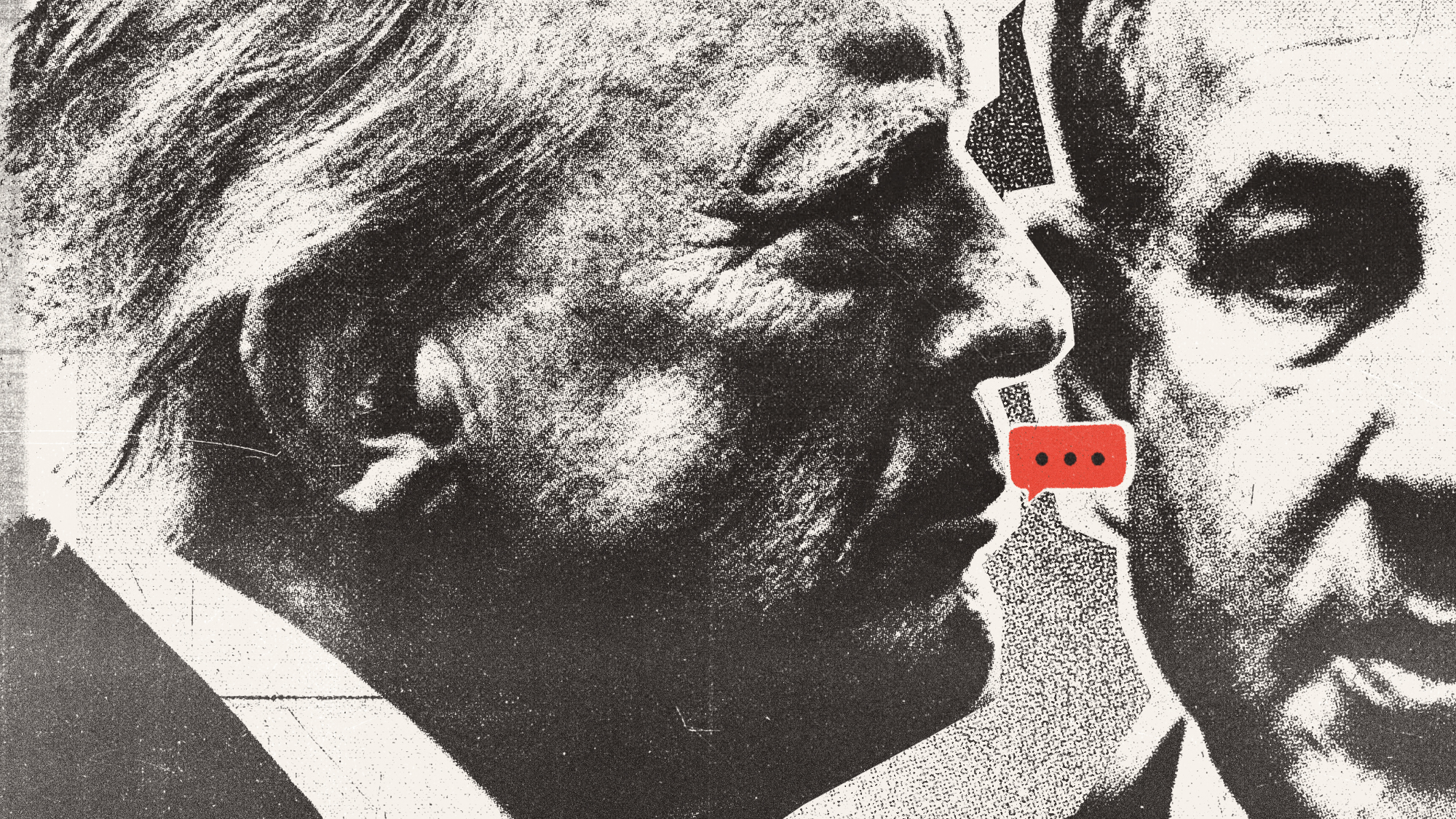

Can Trump bully Netanyahu into Gaza peace?

Can Trump bully Netanyahu into Gaza peace?Today's Big Question The Israeli leader was ‘strong-armed’ into new peace deal

-

‘The Taliban delivers yet another brutal blow’

‘The Taliban delivers yet another brutal blow’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day