How the refugee crisis is teaching us the value of Hussein, Mubarak, and Gadhafi

In foreign policy circles, "stability" used to be a bad word. Not anymore.

Maybe stability isn't such a bad thing after all.

As the refugees continue to stream across the Mediterranean and southeastern Europe, it's worth remembering that for many years stability was considered the problem. In his second inaugural address in 2005, George W. Bush enunciated an understanding of tyranny that had become common after the shock of the 9/11 terrorist attacks:

We have seen our vulnerability — and we have seen its deepest source. For as long as whole regions of the world simmer in resentment and tyranny — prone to ideologies that feed hatred and excuse murder — violence will gather, and multiply in destructive power, and cross the most defended borders, and raise a mortal threat. There is only one force of history that can break the reign of hatred and resentment, and expose the pretensions of tyrants, and reward the hopes of the decent and tolerant, and that is the force of human freedom. [NPR]

While most people want to blame the Iraq War and all the subsequent turmoil on him, Bush was merely channeling an increasingly common disgust with the way business was done in the Middle East. For decades, a realist foreign policy consensus forged during the Cold War had made America and the nations of the West partners with thugs and tyrants across the region. We had empowered He-man porn addict Saddam Hussein, clothes-obsessive Moammar Gadhafi, Soviet hold-over Hosni Mubarak, and the transparently wicked Bashar al-Assad.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The result was a region characterized by underdeveloped resource-economies, religious fundamentalism, and strife. That anger, channeled outward, resulted in terrorism. The Sept. 11 attacks were the shock that finally got us to question the decades-old assumption that stable tyrannies were the best we could expect in the Middle East.

To many, this felt like a near religious revelation about history. This feeling never went away and received a huge boost from the Arab Spring. Here's George W. Bush again, speaking in 2012: "The idea that Arab people are somehow content with oppression has been discredited forever." In the same speech:

"Some look at the risks inherent in democratic change — particularly in the Middle East and North Africa — and find the dangers too great. America, they argue, should be content with supporting the flawed leaders they know in the name of stability," he said. "But in the long run, this foreign-policy approach is not realistic. It is not realistic to presume that so-called stability enhances our national security. Nor is it within the power of America to indefinitely preserve the old order, which is inherently unstable." [Foreign Policy]

There's a facile logic to this, of course. Yes, it was beyond the power of America to preserve the old order indefinitely. No set of regimes is preserved indefinitely. And we weren't doing the work anyway. Mostly we relied on the self-interest of the regimes to do the heavy lifting, and often American commitments to these governments were minimal or transactional in nature. It was partly the sterile, abstract nature of these relationships that made them seem so sordid to officials who had become fascinated by revolutionary violence, and the possibility of dramatic regional change.

That change, under Bush, would be initiated by an American-led domino theory of spreading democracy. Or, under President Obama, a series of lightly tended domestic revolutions called the Arab Spring. Hillary Clinton was just as enamored with the idea of change as Bush, but thought she had discovered a low-investment way of achieving it in Libya: Smart Power. Just a few bombs and the old powers come tumbling down.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In Egypt, we simply backed away from an old ally in Mubarak and watched democratic forces undo him, only to be undone themselves. In Syria, the U.S. political class spent years talking up the possibility of "moderate rebels." The qualifying adjective was by then necessary, because some Americans had realized that not all Middle Eastern paramilitaries were devoted to Lockean conceptions of liberty. We covertly aided and extended that civil war. Perhaps another dictator would fall off the list of realism's dishonorable compromises.

Imagine traveling back to 2003 and discussing current events with a hawk who had been converted to the Bushian faith. If he knew that by 2015 Hussein's regime would be totally deconstructed, that Mubarak would fall victim to a popular uprising, that Gadhafi would fall victim to another popular uprising, and that Assad would be in the fight of his life, he would be jumping out of his seat for joy.

Until you told him the details.

Instead of finding that Middle Eastern Muslims universally aspire to Western forms of liberty, we've discovered that a significant number of children of Muslim immigrants in the West aspire to cut off the heads of infidels and enslave women in the Levant. The 2006 elections in Palestine brought Hamas to power. ISIS controls significant portions of Syria and Iraq. ISIS operates freely in Libya, and even Egypt. Basically, everywhere America goes, ISIS rushes in and starts killing people, sometimes with American-supplied weapons the group has stolen.

Middle Eastern Christians look like they are going through a final genocide. Other religious minorities throughout "liberated" Iraq are being enslaved and raped. The Syrian civil war continues with no end even imaginable. A refugee crisis unlike any seen since World War II is sweeping tens, possibly hundreds of thousands of displaced people from the Middle East to Europe. In response to expressions of European sympathy, Assad seems to be increasing the threats to his domestic enemies, hoping Germany will absorb his problem people. And the onrush of unchecked and unvetted human movement to Europe is inspiring a right-wing backlash and possibly scuttling the Schengen treaty guaranteeing free movement on the continent.

Fourteen years ago, we looked at decades of Middle Eastern "stability" purchased through dirty deals and felt disgusted. Now that we've had 14 years of idealism about revolutionary change, combined with romanticism about the democratic forces on the ground, are we any happier? Bush and others said that the West could not sustain the old order even if it desired to do so, that it was inherently unstable. But it turns out we can't guide the process of destruction and reformation to our desired ends either.

For some reason, a world that is boiling over in violence and cut-throat theocracy makes me nostalgic for the days it was merely "simmering in resentment and tyranny."

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

Disarming Hezbollah: Lebanon's risky mission

Disarming Hezbollah: Lebanon's risky missionTalking Point Iran-backed militia has brought 'nothing but war, division and misery', but rooting them out for good is a daunting and dangerous task

-

Woof! Britain's love affair with dogs

Woof! Britain's love affair with dogsThe Explainer The UK's canine population is booming. What does that mean for man's best friend?

-

Crossword: August 31, 2025

Crossword: August 31, 2025The Week's daily crossword puzzle

-

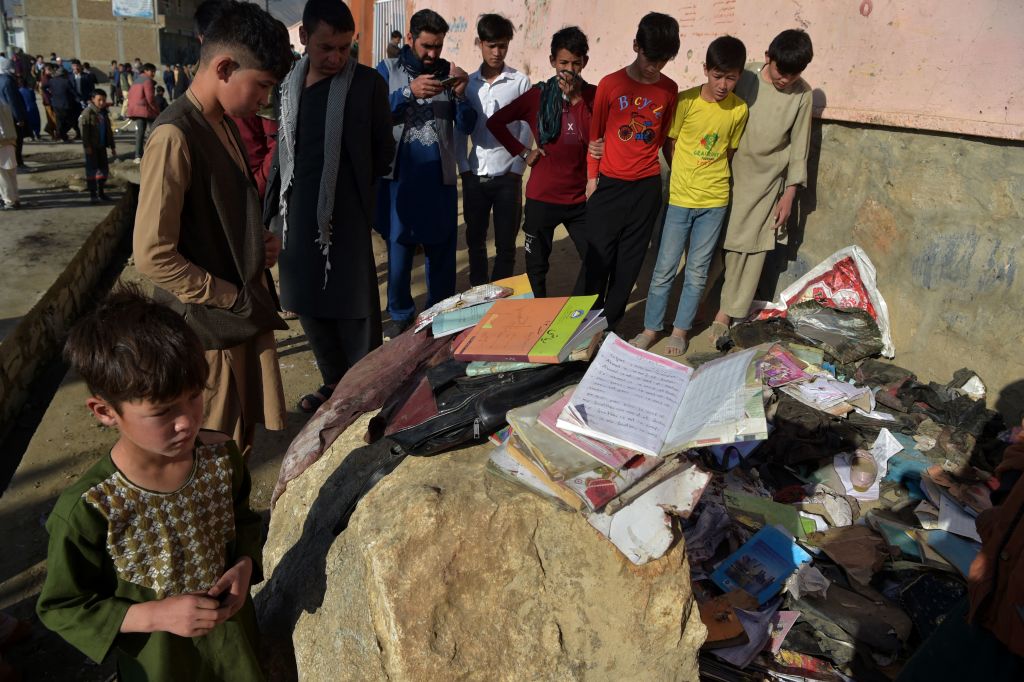

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

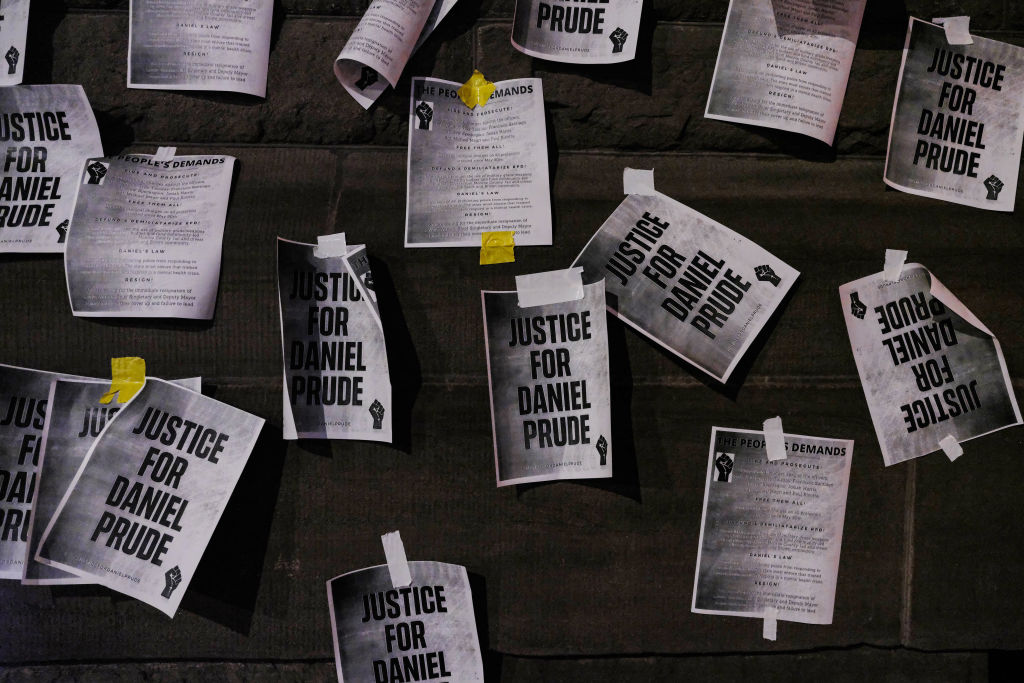

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

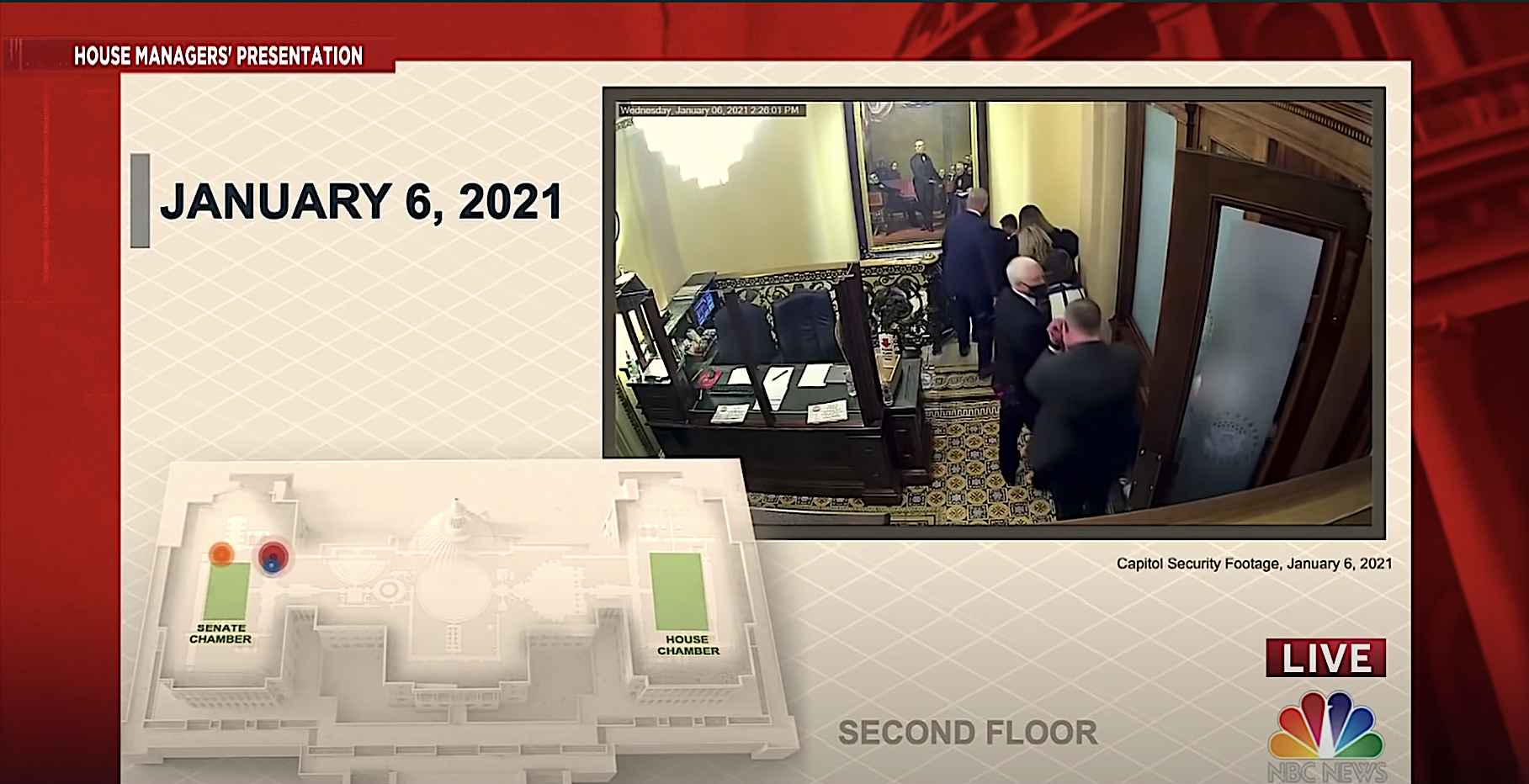

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read