Munich, Lincoln, and Bridge of Spies: The shifting politics of Steven Spielberg

The director's latest offers a fascinating glimpse into his ever-evolving political worldview

Bridge of Spies, Steven Spielberg's latest drama, features a scene in which attorney James B. Donovan (Tom Hanks) — recently returned from East Germany, having built a defense for an alleged Soviet spy — looks out the window of the subway, as playing children scale one chicken-wire fence after another.

The shot recalls an earlier, much different scene in the film: Donovan, on a train through a divided Germany, seeing a family get shot to death as they attempt to scale the Berlin Wall to reach the freedom promised by the West. In the East, people scale walls to escape oppression and are killed for it; in the West, scaling fences is for children, an expression of their limitless freedom and safety.

It's a nakedly political image in an oeuvre that's full of political images — sometimes explicit, and sometimes much more veiled. These themes can be traced all the way back to the beginning of Spielberg's career. 1975's Jaws — that wildly entertaining blockbuster — was released on the heels of the Vietnam War and amidst Watergate. It played to a deeply pessimistic United States, and wove that same pessimism into its DNA. Jaws presents a world where perceived threats from abroad are relocated, quite literally, to U.S. shores. A powerful government figure decides revenue is more important than protecting lives, and as a result, more people are killed. And when Quint and Brody, charged with finding and killing the shark, are "overseas," they turn against one another, in a fracas that's reminiscent of fragging in the Vietnam War.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Of course, a film made 40 years ago — by a director in his twenties, at what was probably the height of modern American discontent — is likelier to be more pessimistic and critical of the U.S. than one made by a wildly successful man approaching 70. Before Bridges of Spies, Spielberg's most recent film, Lincoln, offered an intriguing look at just how much his politics have changed over the years.

Scene after scene of Lincoln consists of the 16th president giving inspirational speeches about the potential of America to be great. "All we've done is show the world that democracy isn't chaos, that there is a great invisible strength in a people's union," he says at one point — a statement that could just as well have come from Donovan's patriotic mouth in Bridge of Spies.

Lincoln, like Bridge of Spies, isn't just a period piece. The film's themes about America's potential have distinctly modern resonances, and screenwriter Tony Kushner — the playwright of the brilliant Angels in America — makes sure the film's allegorical implications extend to LGBT rights. "Do you think we choose the times into which we are born," Lincoln asks, "or do we fit the times we are born into?"

The difference between Lincoln and Bridge of Spies is that their protagonists — while equally unshakeable in their beliefs about American ideals — operate on either side of the governmental line. If the government in Lincoln acts as a guarantor of civil liberties, Bridge of Spies is the story of a government that blatantly disobeys the law, rigs a guilty verdict for a Soviet spy, and then wants to kill him — to treat him, in other words, like they believe the totalitarian Soviets would treat criminals. Donovan is forced to advance his American ideals as a private citizen.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This murky blend of politics and morality might bring another Spielberg film to mind: Munich, his grim examination of the 1972 Summer Olympics massacre in Munich, West Germany. Munich follows Avner Kaufman, whose official ties to Mossad are severed so he can lead a team in assassinating the Black September members responsible for the terrorist attack. At first, Kaufman believes in his mission — but as it goes on, he begins to see it as pointless. Each target who is killed is replaced by another. Black September retaliates by killing more. Others remind him that Israel is also guilty of crimes against innocents. His belief in his country's intrinsically superior values are damaged, and by the end, he himself is so damaged that he is constantly looking over his shoulder for the assassin's bullet, and so haunted by his own immoral acts that he can no longer connect with his wife.

Munich, made in 2005 — when voices opposing the War on Terror were growing louder — ends with a shot of the World Trade Center. Spielberg's argument is clear: America's similar quest for justice was, in its own way, self-defeating.

Ten years later, Bridge of Spies offers a similar moral. The free children scaling the fence, juxtaposed with the challenge Donovan has to face, offers an image of the American Dream corrupted — a reminder that every moment of freedom sits side by side with America's selective erasure of its own values.

Forrest Cardamenis is a freelance critic who recently received a B.A. in Cinema Studies and Journalism from New York University. In addition to The Week, he has written about film for Brooklyn Magazine, Little White Lies, and Village Voice, among others. For more from Forrest, follow him on Twitter.

-

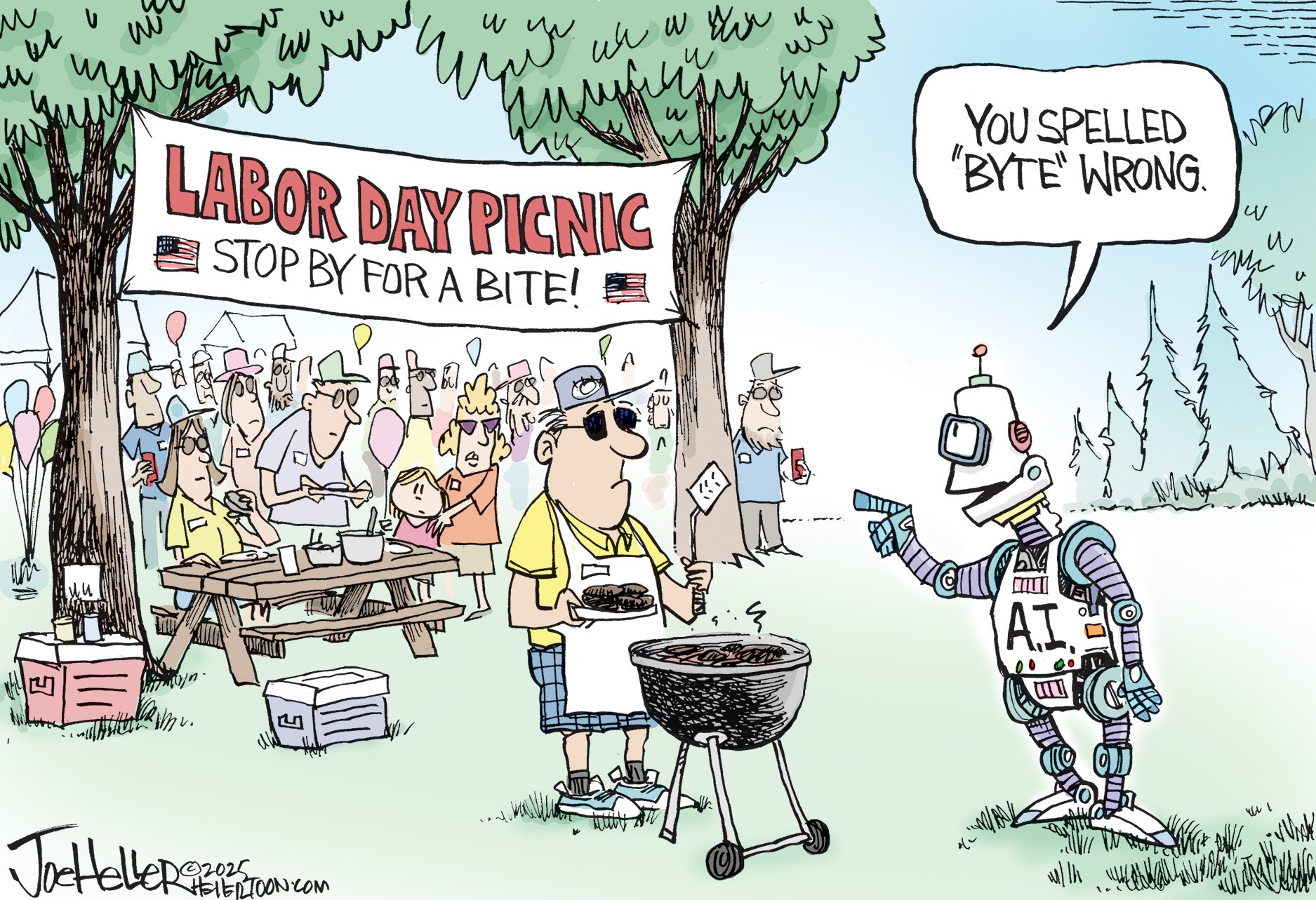

September 1 editorial cartoons

September 1 editorial cartoonsCartoons Monday’s political cartoons include Labor Day picnic, branding strategy, and more

-

What is Tony Blair's plan for Gaza?

What is Tony Blair's plan for Gaza?Today's Big Question Former PM has reportedly been putting together a post-war strategy 'for the past several months'

-

When does autumn begin?

When does autumn begin?The Explainer The UK is experiencing a 'false autumn', as climate change shifts seasonal weather patterns