Taylor Swift and the rise of robot music

Even perfection has its flaws

Perfection is a tricky thing. We need ideals, standards, visions to aspire to. But what happens when the real becomes the ideal? Is anything lost when a work of art doesn't merely strive for perfection but actually embodies it?

In some ways the question is misleading. It's impossible to pin down the melody, harmony, rhythm, and lyrics of the perfect pop song. But a performance is different, since it can be judged on technical criteria alone. A vocal performance, for example, can be perfect in the sense of flawless. Nothing flat, nothing sharp. Perfect phrasing, perfect tone.

But is any musical performance ever truly flawless? For all of human history, the answer was very, very rarely, and with a whole lot of uncertainty surrounding it. The absence of recording technology meant that performances had to be judged in the moment, which also meant that they were subject to the imperfect perception of an audience during a single, unreproducible event. And this meant, in turn, that no performance could ever truly be deemed perfect with any certainty.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Technology has changed this. For one thing, recording allows a performance to be preserved and studied in minute detail by an audience potentially as massive as the entire population of the planet, now and on into the future. For another, studio overdubbing permits the "performance" of a piece of music to be synthesized and stacked up from multiple takes on multiple instruments. Finally, pitch-adjusting processors like Auto-Tune allow even these "performances" to be fixed, corrected, perfected after the fact, yielding a final product that can sound utterly flawless.

It's robot music — music that sounds like it's been performed by a machine. Not only is the vocal line totally free of wavering pitch, but no instrument is off by even a microtone, no beat off by even a microsecond. Any imperfection in the studio performance of the songs has been aurally buffed, air-brushed, and photoshopped away.

If you want to study what's distinctive about robot music, all you need to do is turn on the radio, since just about all pop songs these days have been touched by the trend. But if you want to hear it in its most refined form, the best, most concentrated example is probably Taylor Swift's blockbuster hit album 1989. All 13 of its songs — very much including the album's five ubiquitous hit singles — are masterpieces of mechanical music.

I don't mean the least disrespect to Swift in describing her album this way. She is an enormously talented entertainer. The songs on 1989 would be tuneful, catchy, hook-laden, and infectious no matter how she chose to arrange and produce them. But the fact is that she chose to arrange and produce them as if they were performed live in the studio by androids designed to entertain human beings with absolute precision.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

No wonder it's been such a runaway hit. 1989 is quite literally flawless pop music. Nothing is out of place — not a note, not a vocal line, not a guitar riff, not a drum beat. But not only that. Inhumanly perfect embellishments enhance every hook. This is pop music crafted by a musical Industrial Light and Magic for iMax 3-D, with constantly evolving arrangements that start relatively simple and build to multitracked Technicolor bursts and swirls of keyboard, guitar, and contrapuntal vocal harmonies. To call it ear-candy is to undersell it. 1989 is a bucketful of Skittles, gum drops, and candy corn dipped in chocolate and wrapped in cotton candy.

The best way to appreciate Swift's achievement is to compare the album to the radically reimagined version of the same 13 songs recently released under the identical title by singer-songwriter Ryan Adams.

To be clear, Adams' 1989 is not a great album. The performances lack energy and the arrangements are too often uninspired, with Adams opting for a bland, reverb-saturated, mid-tempo vibe on most of the songs that have been radio fixtures for the past year ("Shake It Off," "Blank Space," "Style," "Bad Blood," "Wildest Dreams"). And the record just plain sounds bad. In place of Swift's translucent sparkle, Adams gives us mud.

Yet the contrast is still illuminating — especially in Adams' slightly more adventurous takes on some of the album's lesser-known songs. The insistent techno-throb of "Out of the Woods" becomes a muted and mournful six-minute ballad; the cheery bubblegum pop of "All You Had to Do Was Stay" is transformed into a driving rocker that features an impassioned vocal performance at the top of Adams' range; the jittery aerobic workout in "How You Get the Girl" gets slowed down and re-envisioned with an acoustic guitar and string arrangement; and the percolating synth-ballad "This Love" benefits from a tasteful piano-based treatment that highlights the song's aching melody.

But we learn the most from standing back and taking a more global view that highlights the dramatically different aesthetic sensibilities of the two artists.

While Swift's pop ambitions lead her to use technology to achieve ethereal, pristine, technical flawlessness, Adams works firmly within rock 'n' roll's more purely populist vision that treats imperfection as a virtue. Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, Janis Joplin, Lou Reed, Carole King, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Tom Waits, Bruce Springsteen, Joe Strummer, Elvis Costello, Michael Stipe, Tori Amos, Bob Mould, Aimee Mann, Kurt Cobain — these and many other rock artists produced music sung and performed by regular, flawed, broken human beings. Its beauty, its power, its passion grew out of and was embedded in its imperfection. The music was the sound of an ordinary man or woman roused by joy, anger, or pain to break out in song as an expression of authenticity and in search of a chance at catharsis, if not redemption.

For one example among thousands, take a listen to one of the best album tracks of the grunge era: Pearl Jam's "Better Man." When I first heard it, in 1994, still a few years before the Auto-Tune revolution, I noticed that Eddie Vedder's voice was off-key for much of the song. But I didn't care. It's a song of anger, hopelessness, and regret, and the raw edge of the vocals seemed to enhance the intensity of the feeling.

But today? With ears trained to expect digitized perfection from vocalists, it's become impossible to listen to the song without wincing. It would never be released today. The band would be laughed out of the offices of Sony Music. Vedder wouldn't make it past first-cut auditions for The Voice.

No one wants to hear bad music. Great technical performances have always been appreciated and rewarded. But there are other standards, too. Leonard Cohen, another undeniably imperfect singer, expressed one of them quite beautifully in "Anthem" from 1992:

Ring the bells that still can ringForget your perfect offeringThere is a crack in everythingThat's how the light gets in

Those lines once could have served as the motto for a genuinely populist form of pop music. Now they stand as its epitaph.

In the world we can hear coming into being in Taylor Swift's music, there will be no cracks in anything at all.

How will the light get in?

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

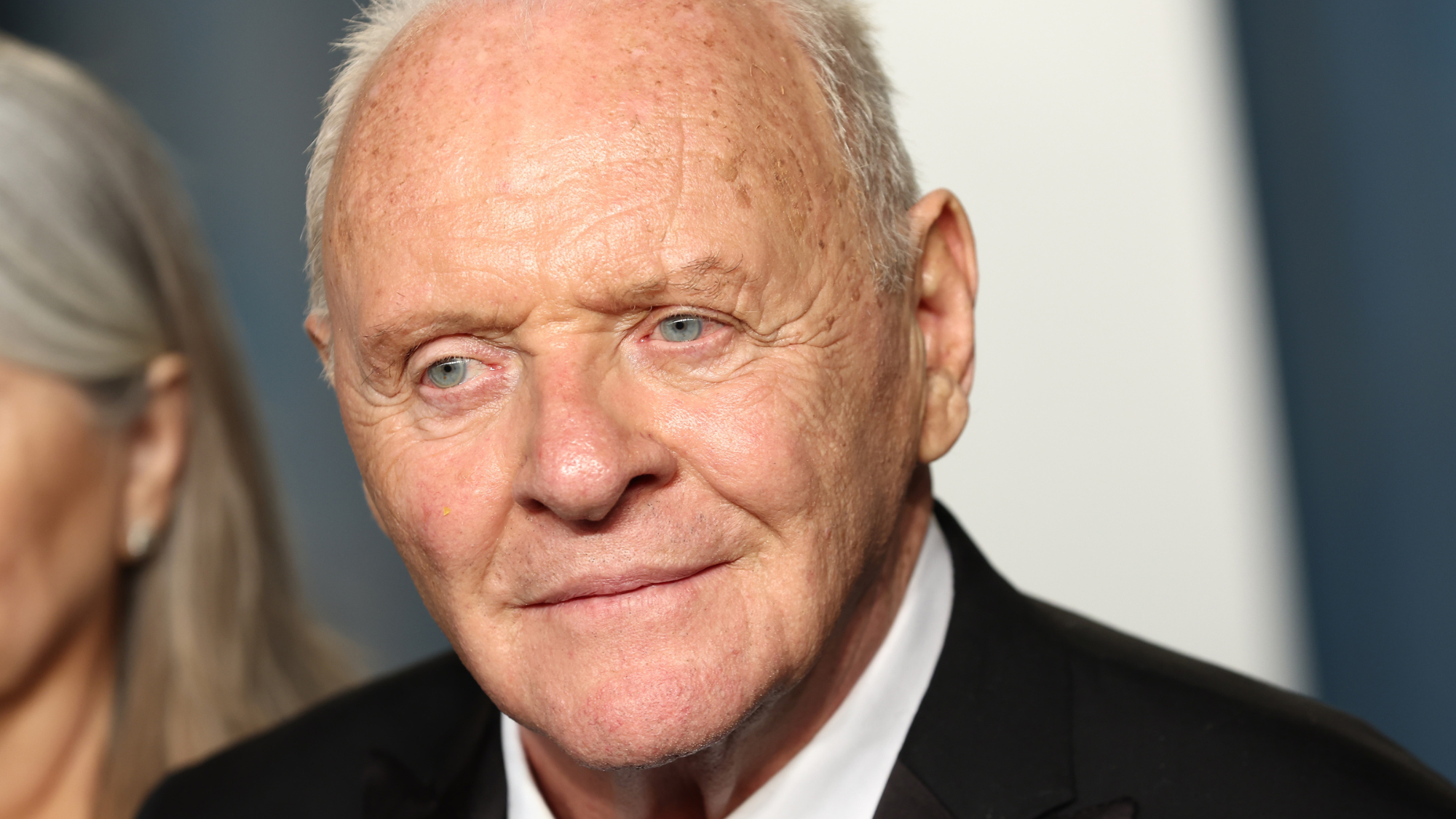

We Did OK, Kid: Anthony Hopkins’ candid memoir is a ‘page-turner’

We Did OK, Kid: Anthony Hopkins’ candid memoir is a ‘page-turner’The Week Recommends The 87-year-old recounts his journey from ‘hopeless’ student to Oscar-winning actor

-

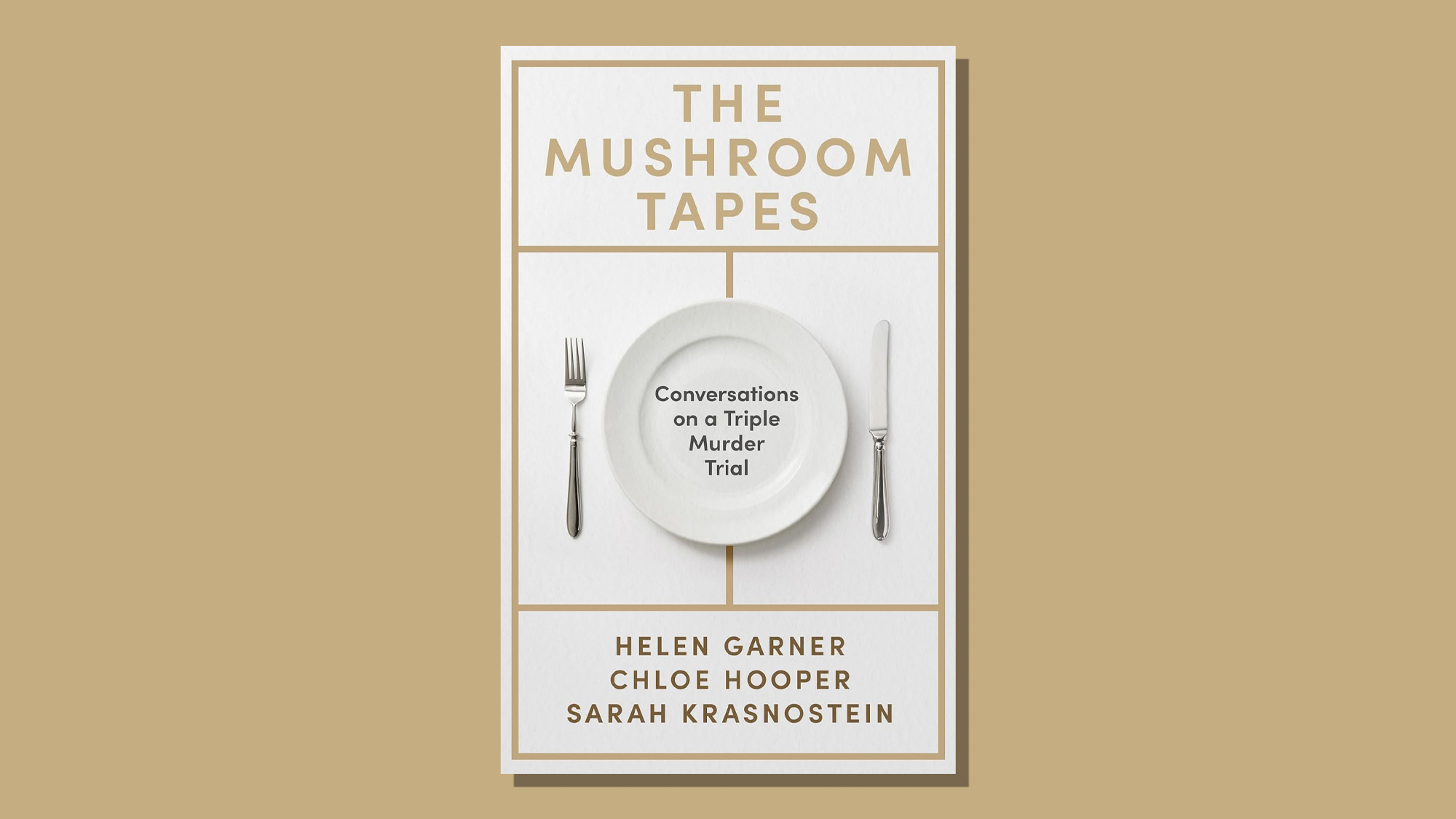

The Mushroom Tapes: a compelling deep dive into the trial that gripped Australia

The Mushroom Tapes: a compelling deep dive into the trial that gripped AustraliaThe Week Recommends Acclaimed authors team up for a ‘sensitive and insightful’ examination of what led a seemingly ordinary woman to poison four people

-

Turner: The Secret Sketchbooks – a fascinating portrait of the great painter

Turner: The Secret Sketchbooks – a fascinating portrait of the great painterThe Week Recommends BBC2 documentary examines the rarely seen sketchbooks of the enigmatic artist