A millionaire has hidden a chest full of gold in the Rockies. The map? A poem.

This treasure is buried in a riddle

If not for the treasure, it seems unlikely that Forrest Fenn and Darrell Seyler would ever have crossed paths. Fenn is an 85-year-old retired art dealer from Santa Fe; Darrell is a 50-year-old former cop living in Seattle. Fenn grew up exploring Yellowstone National Park; Darrell bounced in and out of foster homes. After a bad tour in Vietnam, Fenn wandered the plateaus and canyons of the desert Southwest; after a divorce, Darrell spent a few unfortunate months on the Dallas club scene.

Yet the two are inextricably linked by an incredible fact: For the past three years, Darrell has been searching the Rocky Mountains for a chest filled with an estimated million dollars in gold, and Fenn knows where it is. In fact, he put it there.

Fenn has spent his life amassing treasure. As a kid growing up in the 1930s in Temple, Texas, halfway between Dallas and San Antonio, he hunted for arrowheads with his father. Every summer, his family drove their 1936 Chevy to Yellowstone National Park, where Fenn pulled trout from the streams and scoured the riverbanks looking for agates. By 13, he was a professional fishing guide in the area. At 16, he read Osborne Russell's Journal of a Trapper — about the mountain man's explorations in the Yellowstone Valley — and set out with a friend to wander the same territory. "The mountains continue to beckon me," Fenn wrote in his 2010 memoir, The Thrill of the Chase. "They always will."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 1950, at age 20, he left the mountains to join the Air Force, eventually flying fighter jets in Vietnam. He was shot down twice, the second time spending a night alone in the jungle hiding from Pathet Lao forces before being rescued. He was discharged in 1970 and later moved to Santa Fe to start an art gallery, selling paintings, sculptures, and artifacts he'd traded for or found throughout the Four Corners region.

When I met Fenn at his home in September of last year, a museum's worth of mementos adorned his study — 10 Native American headdresses, a wall of moccasins, proof sheets for A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court full of Mark Twain's own pencil markings. Some are worth a lot of money; others are valuable only for the memories they represent.

"There's an old saying: 'I never knew it was the chase I sought and not the quarry,' " Fenn says. "Isn't that a nice little phrase?"

In 1987, Fenn's father took enough sleeping pills to end a protracted fight with pancreatic cancer. The next year, Fenn was diagnosed with kidney cancer and given a 20 percent chance of surviving three years. He decided he'd go out with a flourish of minor mystery. He'd fill a 10-by-10-by-5-inch bronze box full of gold coins and jewels, carry it to a final resting place, set it down, and wait to die. The only way to find him — and the treasure — would be to follow the clues he'd leave behind in a poem.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Everything was going according to plan — he'd written the poem and filled the chest with 42 pounds of sapphires, rubies, gold coins, ancient jade carvings, a pre-Columbian gold frog, and a turquoise bracelet — and then the cancer went into remission. Fenn put his plan on hold until 2010, when he turned 80 and decided to revive it. So, like the scores of outlaws and miners whose legends still have shovel-wielding optimists wandering the American West, he stashed his prize. Then he printed the poem in his memoir and waited for the story to spread.

It's Thanksgiving weekend, and Darrell and I are speeding east from Seattle toward Wyoming on I-90. When I stopped by his place for the first time, two weeks ago, Darrell said point-blank that he knew where the chest was.

Like a lot of searchers, Darrell learned of the Fenn treasure while perusing the internet on a work break. After a bit of research, he decided that he knew — absolutely knew — where it was: a certain grove of aspen trees in Yellowstone National Park. He had found it on Google Earth, and it lined up with some of Fenn's clues. He went to retrieve the treasure in January 2013, and discovered that like every other searcher thus far, he was wrong.

But hunting for treasure was like living out his childhood dreams; he'd had Raiders of the Lost Ark on repeat as a kid. He spent most of 2013 dissecting Fenn's clues, and made the 13-hour drive to Yellowstone 17 times between January 2013 and May 2014.

Darrell is hardly unique. Fenn estimates that at least 30,000 people have looked for the chest, and searchers range from weekend enthusiasts to semiprofessional hunters to unrepentant fanatics. In 2013 in Tererro, New Mexico, a man was charged with damaging a cultural artifact for digging beneath the white cross of a roadside memorial. Another man dug up graves, even though Fenn has been very careful never to say that he buried the treasure — it's "hidden." A woman in Chicago has spent $100,000 on searches she can't afford. "It's a monster that I created with my story," Fenn told me.

Back at Darrell's place, Darrell had shown me a picture he took from the bottom of a 50-foot cliff. He was looking at this photo last night and realized that the chest — right there, can you believe it? — was tucked into the rocks halfway up. It was a location he'd searched previously, just not the cliff. "What I thought was, 'This is the lid, that's the top, and that's the latch,'" he said. "Can you see that?"

Then he talked me through his solution to the first three clues in Fenn's poem. I thought, "Damn, that's a good solve." Then he talked me through the rest of his evidence, and I thought, "Holy s---!"

Our plan is to drive 12 hours through the night, get the treasure, and drive right back. We doze in shifts. Around 3 a.m., we stop at a Walmart to pick up rope, gloves, and binoculars. The clerk gives us a funny look when we check out — we're a few full-face stocking caps away from a burglary kit.

Back on the road, the late-November sunrise reveals snow like a hasty coat of primer on the mountains. But it's warmish when we don snowshoes and set out to a location I've sworn not to reveal. Approaching the top of the 50-foot cliff, Darrell says we'll tie off a rope so he can climb down to the spot. He hasn't brought a climbing harness, however, just a length of fraying cord and the $15 Walmart rope. After watching Darrell tie a knot, I replace it with a real one.

Fenn has repeatedly said that the treasure is "not in a dangerous place." He hid the chest when he was 80 years old and tells searchers not to look anywhere he couldn't have gone. But Fenn is also no ordinary octogenarian, Darrell argues. Also, Fenn made his money selling native artifacts from the Southwest. Where did Southwestern cultures hide valuables? On cliffs.

So down Darrell climbs, to the edge of where things turn vertical. But for all his enthusiasm, Darrell is afraid of heights, and that fear speaks to him on a deeper level than treasure. He decides he wants a better rope, better footing. He wants to survey the cliff from down below so he knows where he's going. The sun is getting low. Let's come back tomorrow, he says.

Like something out of an airport mystery novel, Fenn's poem is a rhyming literary treasure map: six stanzas, nine sequential clues, all as vague as a jigsaw puzzle strewn across the table. The key to solving it, most searchers agree, is figuring out the line "Begin it where warm waters halt." From there you're looking for a "canyon down," and then some sort of "home of Brown." Find all three in succession and maybe you're in business. Outside of that, there's hardly a consensus as to which lines are real clues.

Subsequent information from Fenn has narrowed the search area to elevations between 5,000 and 10,200 feet in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and anywhere north of Santa Fe in New Mexico, but those states are chock-full of hot springs, warmish lakes, brown trout, brown bears, and ranches and mountains named for one Brown or another, so it's hard to get more zeroed-in than that.

Dal Neitzel, a searcher from Lummi Island, Washington, who runs a website about the hunt, has gone looking for it more than 50 times. A longtime underwater treasure hunter, Neitzel first heard of Fenn while searching for a sunken ship in Uruguay with Fenn's nephew, Crayton Fenn, who told story after story about his madcap uncle. "I thought, 'This is going to be simple!'" Neitzel said. "I've found lots of stuff with no directions. If this guy is going to give me some, this will be easy." That was five years ago.

Fenn once wrote that most searchers overcomplicate the clues, resting their solve on obscure knowledge or hidden codes — bending the poem to fit their solution rather than the other way around.

Despite Fenn's insistence that searchers focus on the text, nothing seems off-limits. There are as many solutions to the poem as there are nooks and crannies in the Rocky Mountains. For example, if you start at Flaming Gorge Reservoir in Wyoming (where warm waters halt) and continue downstream 15 miles (too far to walk), you come to a park named for French Canadian fur trapper Baptiste Brown (home of Brown). Follow the river and you come to Fort Misery, where pioneer Joseph Meek hid out among notorious outlaws (no place for the meek). The geography, the trappers, and the wordplay all read like classic Fenn. But: no treasure.

Go online and you'll find folks parsing Fenn's every word for hidden meanings and contradictions. The level of scrutiny is formidable — some searchers have gone so far as to compile all of Fenn's published spelling errors looking for patterns — but it's also a reminder of just how much collective brainpower is going into solving this thing.

In other words, Fenn's poem isn't just a riddle. It's also a race.

The next morning, our plan is the same. Hike in, get the treasure, and cannonball home. Except this time Harry Greer, a friend of Darrell's, comes with us. He wants to earn the money Darrell promised him, so he volunteers to be the one who rappels down the cliff. "Are you comfortable with this?" I ask. "No," he says, dropping over the ledge. "But I've got a lot of bills to pay."

Of course, the rope-corset crushes his chest immediately. As he continues to lower himself, I track his progress via grunts of pain echoing through the wood. Darrell is below, dodging falling rocks and excitedly guiding him to the treasure. "Check up there, yeah, to the left, on that ledge," says Darrell.

"It's not here, boss," Greer says. "Check on that ledge," Darrell replies. "Dig around a little bit. It's there."

Greer gets a knife out and scrapes it along every flat surface. He looks down at Darrell, who is waiting like a puppy for a treat, and then searches everything again. "Nothing but rock. I'm sorry."

I didn't expect to hear from Darrell for a while after our unsuccessful hunt. On the drive home, he told me that I could start searching his spot if I wanted. He was done: no more poem.

Then, one morning a few weeks later, I get several emails in a row, then a text to let me know that he sent an email. A few hours later he calls. He's back on the hunt.

THE POEM

As I have gone alone in there

And with my treasures bold,

I can keep my secret where,

And hint of riches new and old.

Begin it where warm waters halt

And take it in the canyon down,

Not far, but too far to walk.

Put in below the home of Brown.

From there it's no place for the meek,

The end is ever drawing nigh;

There'll be no paddle up your creek,

Just heavy loads and water high.

If you've been wise and found the blaze,

Look quickly down, your quest to cease

But tarry scant with marvel gaze,

Just take the chest and go in peace.

So why is it that I must go

And leave my trove for all to seek?

The answers I already know

I've done it tired, and now I'm weak.

So hear me all and listen good,

Your effort will be worth the cold.

If you are brave and in the wood

I give you title to the gold.

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in Outside. Reprinted with permission.

-

Long summer days in Iceland's highlands

Long summer days in Iceland's highlandsThe Week Recommends While many parts of this volcanic island are barren, there is a 'desolate beauty' to be found in every corner

By The Week UK Published

-

The Democrats: time for wholesale reform?

The Democrats: time for wholesale reform?Talking Point In the 'wreckage' of the election, the party must decide how to rebuild

By The Week UK Published

-

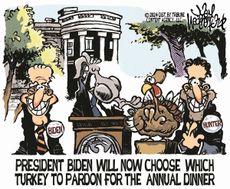

5 deliciously funny cartoons about turkeys

5 deliciously funny cartoons about turkeysCartoons Artists take on pardons, executions, and more

By The Week US Published