Western troops can't stop ISIS. And Saudi Arabia's won't stop ISIS.

We need to stop kidding ourselves that there is a quick military solution to ISIS

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some problems don't get solved because those who have the will don't have the way — and those who have the way don't have the will.

Defeating ISIS is just such a problem.

The West — especially after Paris and San Bernardino — has the will, but has no way. The Middle East has the way, but not the will. Nothing makes these dual points more obvious than recent GOP bloviating and the bogus anti-terrorism military alliance of 30-plus Muslim countries that Saudi Arabia spearheaded earlier this month.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If will alone could defeat ISIS, then sending a fighting force of a dozen or so Republican presidential candidates (with the exception of Rand Paul) might do the job all by itself, at least judging by all the saber rattling they did on the debate stage last week. Then again, the GOP candidates managed to offer two different strategies to deal with ISIS — neither of which will work.

Ted Cruz, who even looks like a hawk, recommended carpet-bombing ISIS till the "sand glows in the dark." He had to back away from this idea when it was pointed out that such a campaign would mean dropping bombs on highly populated ISIS-controlled cities like Raqqa. This would not only generate massive civilian casualties — a war crime under international law — but wouldn't be as effective as he thinks, since ISIS, a highly mobile force, would quickly relocate its men and arms. (And if you think ISIS is dangerous now, wait till the children orphaned by American bombs grow up.)

The other suggestion, floated by Lindsey Graham, an unrepentant neocon (who is nevertheless endearing for his unequaled ability to land a punch on Trump), involves contributing 10,000 U.S. ground troops as part of a regional army. Marco Rubio and others have endorsed variations of this idea, and it is enjoying renewed support among the American people in the wake of the San Bernardino attack. But it's unclear that such resolve would endure much past the first videotaped beheading or burning of a captured American soldier. Indeed, the twin lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan are that even deep domestic support tends to peter out in a long, protracted war. There is little reason to think that obliterating ISIS would be a quick in-and-out job.

But the main drawback of an American ground force — even one that is part of a broader coalition — is that it plays right into the hands of ISIS. Under its reading of the Islamic scriptures, there is supposed to be a final showdown with the Great Satan before the countdown to the apocalypse begins, as The Atlantic's Graeme Wood has reported. U.S. ground troops would only energize ISIS's call to arms.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

An exclusively Muslim fighting force — in which it isn't the West vs. ISIS — wouldn't suffer from that problem. And this idea's huge upside is that if Islam stamps out its own fanatical offshoots, that would help cure the growing tendency in the West to equate Islam with terrorism. This would make it much easier to contain the growing anti-Muslim backlash that only drives a wedge between the West and its Muslim population — delivering more recruits to ISIS. That's why the statement by Prince Turki al-Faisal, the former Saudi ambassador to the U.S., that Islamic terrorism is the "seed of evil" that the Muslim world has "let out of the can" and needs to take responsibility for vanquishing was so encouraging.

Still, it would be a mistake to invest too much hope in the Saudi-led anti-terrorism coalition.

First of all, the irony that the country most responsible for creating the jihadi monster now wants to lead the fight against it isn't going to be lost on the Muslim world. There is huge reason to be skeptical of this initiative just on the face of it.

Then again, Saudi Arabia certainly has reason to hate ISIS, which has launched more attacks and has killed more people in Saudi Arabia than the 14 people killed in the lone ISIS-inspired massacre in San Bernardino. Indeed, since ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi's speech last year instructing his followers to target the kingdom, Saudi Arabia has faced nearly a dozen attacks with the two deadliest this year claiming 34 lives.

But here's the thing: Saudi Arabia largely tolerates ISIS terror, because unlike the U.S., it has other bigger worries.

ISIS is a Sunni group that has mostly targeted Saudi Arabia's Shiite minority. This makes it hard for the rulers to gin up anti-ISIS outrage, especially since for the last many years they have been busy trying to quash a Shiite insurgency — inspired by its mortal enemy, Iran — in Yemen that the whole country regards as a far bigger existential threat.

But this brings up another fundamental problem. Saudi Arabia's coalition will be successful only if all Muslim countries set aside their internal divisions and join ranks against the terror group. That would mean Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shiite Iran burying the hatchet. This would basically be like the NAACP teaming up with the KKK to fight climate change. It is hardly a coincidence that Iran — along with its Shiite client states like Algeria and Iraq — are not part of Saudi Arabia's coalition, points out Cato Institute's Emma Ashford.

All of this suggests that the coalition is more of a PR stunt meant to get America and the West off Saudi Arabia's back than a serious solution to deal with the ISIS menace. But, then, the hard truth is that there may be no good solutions — only bad and less bad ones.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

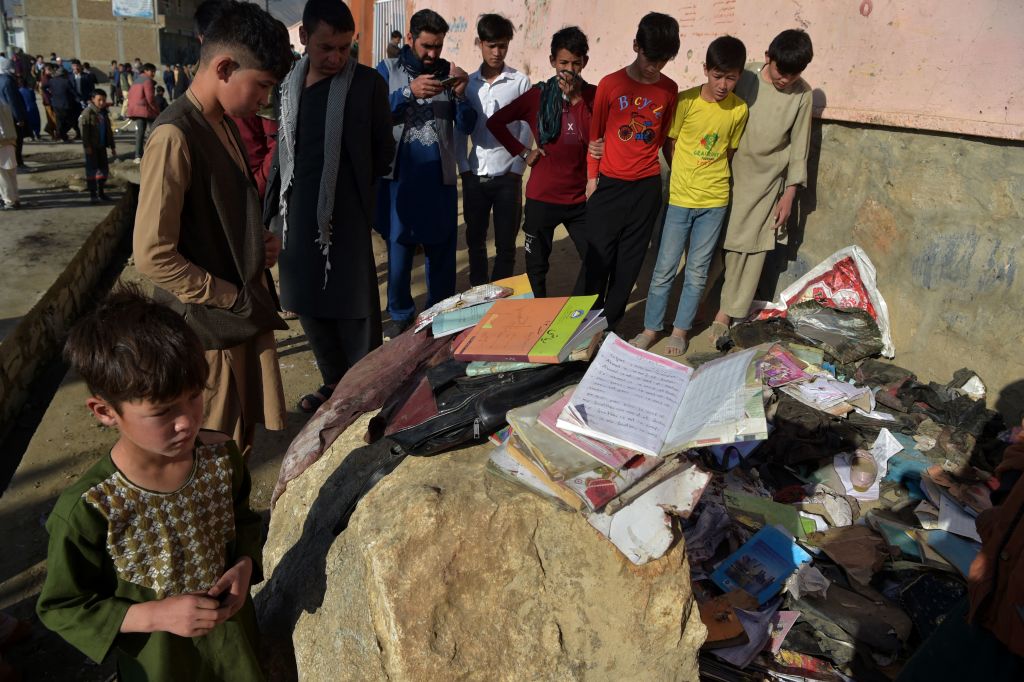

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

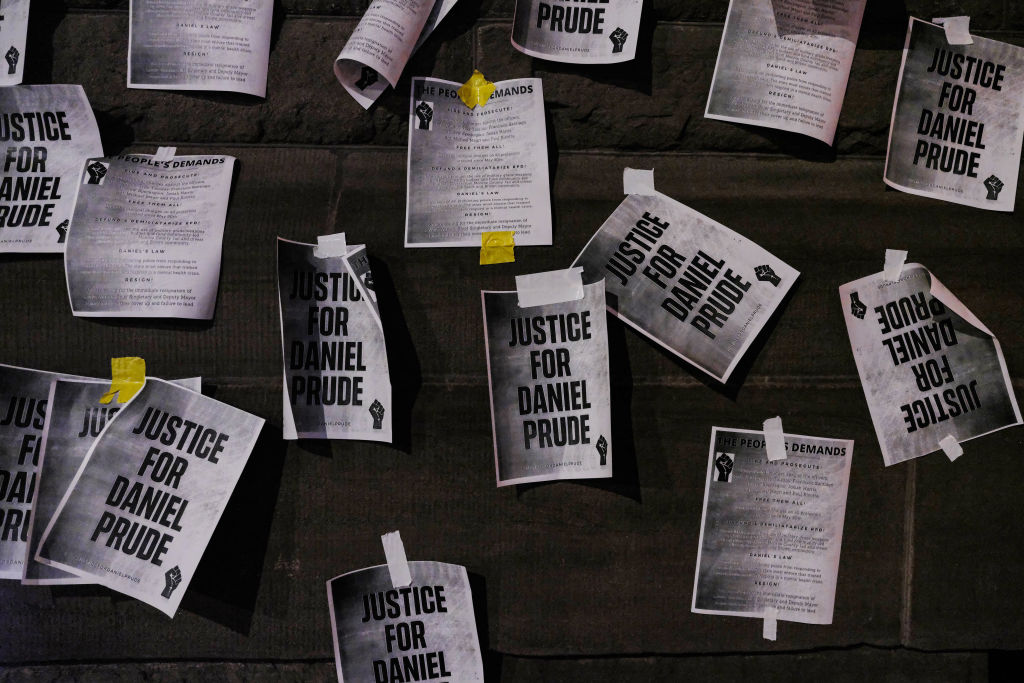

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

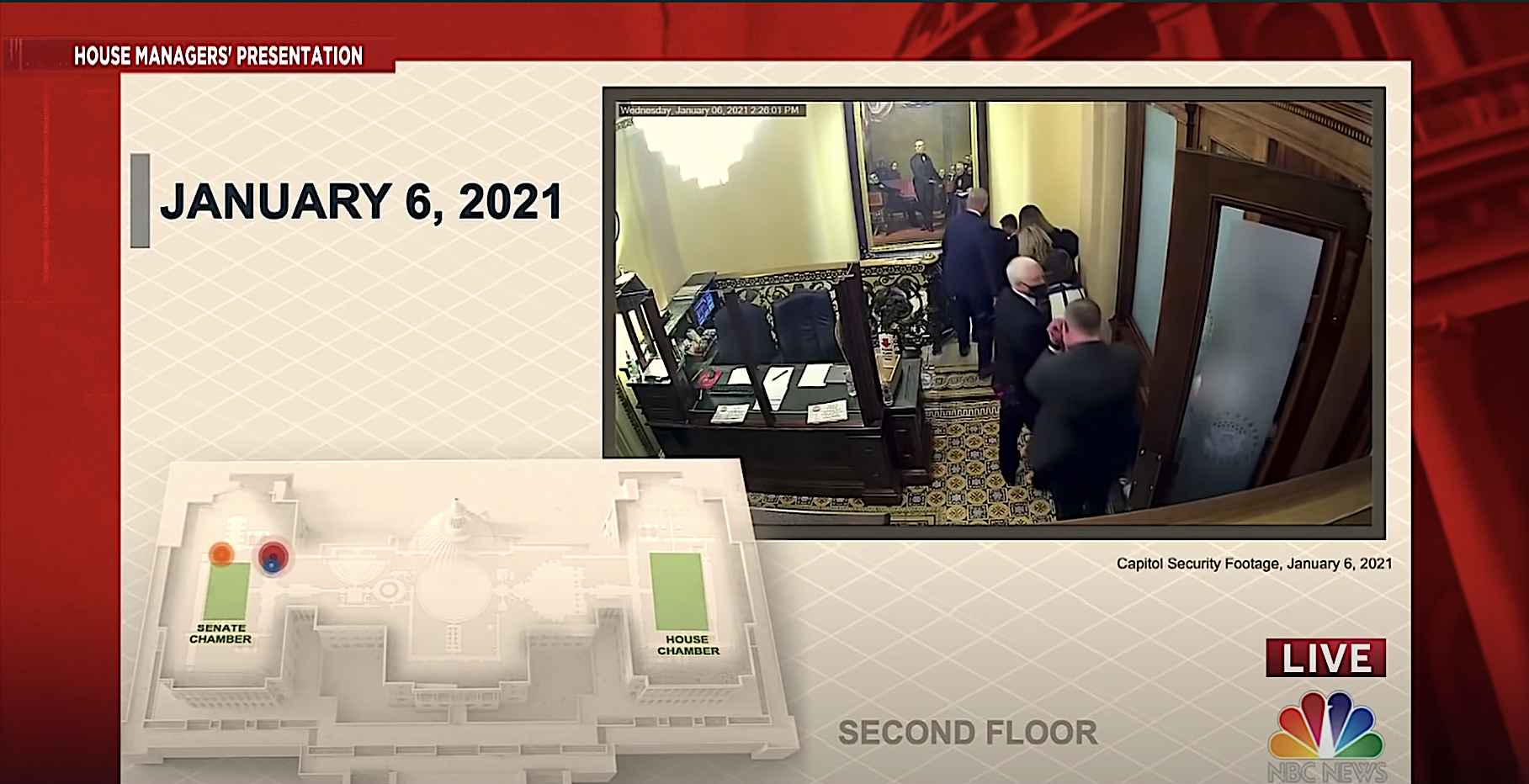

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read