My year watching movies by anyone but white men

I gave up watching all movies made by white American men last year. It was even more difficult than I thought.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I haven't see the new Star Wars. Not because I don't like or haven't seen the original series — I haven't seen Star Wars: The Force Awakens because its director, J.J. Abrams, is a white American man. And that would have meant breaking my rules.

Beginning last April, I challenged myself to watch and read anything but stories authored by white men from Western countries until the end of 2015 (you can read my methodology and reasoning here and see the list of all the movies I watched here). While it turned out to be fairly easy to read only books by women, movies were a different story. It was sometimes impossible to go to a movie directed by a female director or person of color on any given day at the theater.

It's no secret that the lack of women in Hollywood is a major systematic problem. Recently Meryl Streep counted the number of female critics whose reviews are represented on the aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes: "I went deep, deep, deep, deep — and found the numbers alarming," Streep said. "Of those allowed to rate on the Tomatometer, there are 168 women. And I thought, that’s absolutely fantastic. If there were 168 men, it would be balanced. If there were 268 men, it would unfair but I'd get used to it. If there were 368, 468, 568 […] Actually there are 760 men who weigh in on the Tomatometer." The New York Film Critics circle isn't any better: 37 of its 39 critics are men, according to Streep.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In fact, film culture remains such a boy's club that The New York Post saw it perfectly fit to run an article with the headline, "Women are not capable of understanding GoodFellas" last year; likewise, veteran film blogger Jeff Wells felt it appropriate to deem a movie too "unflinchingly brutal" for women to go see.

As a friendly reminder in case you've forgotten: It's the 21st century! And for what it's worth, that "unflinchingly brutal" film was my second favorite movie of the year.

But if it's hard to find a welcome space for women in front of the big screen, it is even harder to find them behind the camera. As writer and director Leslye Headland told The New York Times recently, "Without the benefit of Google, ask anybody to name more than five female filmmakers that have made more than three films. It's shockingly hard." A "top entertainment boss" speaking on anonymity for the same article put it more bluntly: "Not that many women have succeeded in the movie business. A lot of 'em haven't tried hard enough. We're tough about it. It's a 100-year-old business, founded by a bunch of old Jewish-European men who did not hire anybody of color, no women agents, or executives. We're still slow at anything but white guys."

And while it's dismal for women, it is even worse for people of color — especially for women of color. "Any film that you see that has any progressive spirits that is made by any people of color or a woman is a triumph, in and of itself," Selma director Ava DuVernay told NBC News.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So now that you know how horrible these disparities are, I'll come clean: I slipped up on my challenge a few times. Once I went to a documentary about trains in China under the assumption it was a Chinese director — only to find out afterward the director was a white guy from Michigan. I broke my rule again when I snuck to a rare Jacques Rivette screening after getting hooked on the director's epic 13-hour project Out 1. And as for Out 1, I watched it on the grounds that it was conceived originally as for TV (and my project didn't apply to television nor to short films). I also made an exception for films I needed to watch for work- or school-related purposes, or that screened at the New York Film Festival.

But I don't feel that bad about it. A large part of the challenge was simply to highlight for myself how difficult it is to see films by women or people of color. I pay a monthly fee to go to unlimited movies in theaters, but I ended up losing probably hundreds of dollars on the service this year because I couldn't see almost anything at the multiplex. Even repertory theaters I love were often barren of films I could attend. Most days I would open Screen Slate — a handy newsletter listing all the independent and repertory movies playing in New York on a given day — and delete it from my inbox after looking through the usual parade of French auteurs and noir classics.

That being said, New York is still a better city than most to be a cinephile, and streaming services like Netflix, Mubi, Fandor, and Hulu all made my project easier — as did splurging on a region-free Blu-Ray player and making runs to Scarecrow Video whenever I was back in Seattle to visit family.

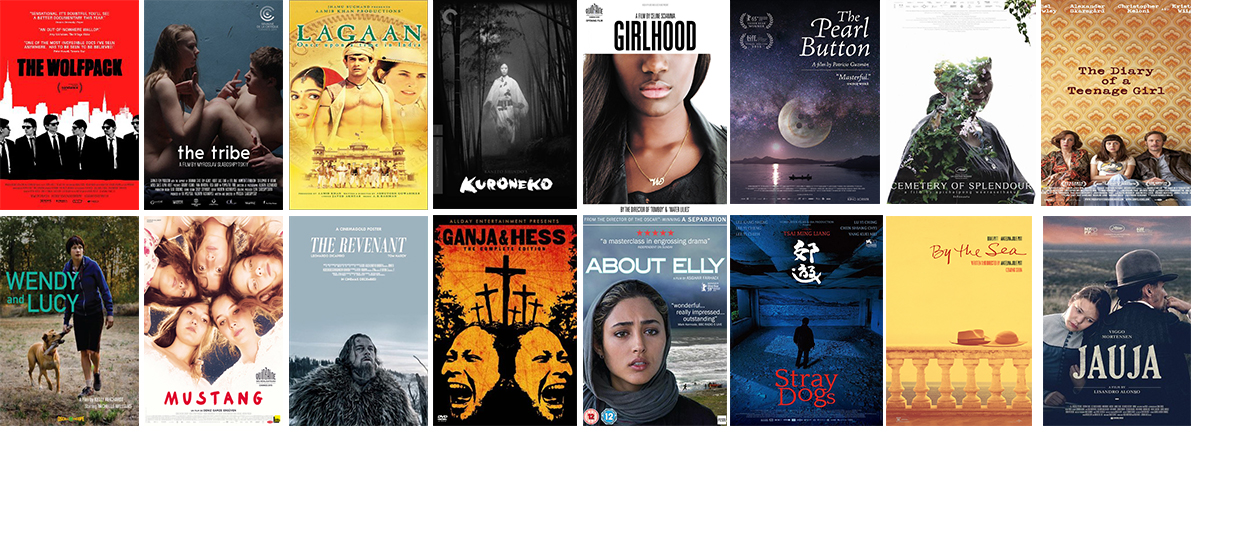

The payoff was more than worth it: I saw films from at least 25 different non-Western countries including Mauritania, Lebanon, Malaysia, the Philippines, Morocco, Iran, Chile, and Mexico — every continent on the planet was represented except for Antarctica. My favorite film of the year, The Tribe, is told entirely in Ukrainian sign language with no subtitles, an experiment that takes empathy to the extreme. It is a triumph of the universal language of cinema: I might not be able to understand what the characters are signing to each other, but I can understand the human experience behind their expressions, their pain, their lust.

In another discovery, I was charmed by the Turkish sisters in Deniz Gamze Ergüven's Mustang, a film that was nominated for a foreign language Academy Award and which transcends the category. With masterful work in cinematography, acting, and directing, Ergüven's Mustang draws comparisons to Sofia Coppola's The Virgin Suicides; it is as much about tradition as it is about feminism and the brutal loss of innocence that forces girls to change into women.

I was also impressed by the films of women directors working in my own language and region. Angelina Jolie's mighty By the Sea explores a painful, crumbling romance from a woman's perspective; similarly, Sam Taylor-Johnson's interpretation of Fifty Shades of Grey probably would have crumbled under a male gaze but instead worked as a subversive, startling celebration of female sexuality. In fact, three of my 10 favorite movies last year were directed by women — and while it's still a lower percentage than I'd like, keep in mind that not even one female director was nominated for the Oscars this year. (Only Kathryn Bigelow has ever won.) We all need to do better, and it's clear we still have so far to go.

Even though I'll be watching films by white men again this year, I can't help but be hyper-aware of the choices I'm making with my money and my time; as a writer, I also realize my own responsibility in helping shape the conversation around film. Maybe if we had a bigger say, we'd see it reflected in what movies are getting made and seen.

This much I know — I will watch films by white men again this year, but it'll be the women I can't take my eyes off of.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers