The dirt beneath your home is way more valuable than your home. It's time we tax the dirt.

Forget property taxes. We need dirt taxes.

If you bought $100 worth of land in Manhattan in 1950, it would have been a mundane investment with a low rate of return for several decades. But in the mid 1990s, it rocketed upward. By 2014, that $100 of land would be worth $3,500.

"Had an investor purchased a plot of land in Manhattan in 1993, the investment would have risen by a factor of 28 in inflation-adjusted dollars, and the buyer would have realized a real annual return of 16.3 percent per year!" Anna Scherbina and Jason Barr wrote in an analysis at Real Clear Markets. If instead you had ignored the actual land and put money into a Manhattan condo in 1994, it would have risen by a factor of three and returned 4.38 percent per year.

Herein lies the great secret of the housing crisis. The real value is not in our houses or condos, but the dirt they sit on.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

An American political economist and journalist named Henry George hit on this point way back in 1879, and wrote a whole treatise on it. The supply of land is fixed, so price signals cannot induce people to make more or less of it — the way it usually works with other goods and services. But as George pointed out, if exciting stuff is going on somewhere, and lots of jobs and incomes are being produced (like in Manhattan), people will want to move there. That increased demand falls on a fixed supply of land, and up go the prices. This means increasing the value of land is an ecological effect, not one caused by human effort, like when the value of a house goes up because you refurbished it.

Someone could buy an empty plot on the frontier, wait for a city to pop up around them, then sell the plot and make a killing in income, even though they literally did nothing productive — something that isn't supposed to happen under market capitalism.

If you buy a house, you're paying for the land it sits on. If you buy a condo, you're helping to pay for the land it sits on — ditto if you pay rent for an apartment. Land prices also drive up the costs of restaurants, entertainment, retailers, and other goods and services, since all those suppliers have to build their own housing costs into the prices they charge.

So what do we do about it? There are three key things.

The first is deregulation: Historical preservation laws, zoning restrictions on density, parking requirements, and so on can all hold back the creation of new housing supply. If demand for land is driving up housing prices, more housing supply can drive them back down. Break those regulations up, and developers can build more on the same finite supply of land.

Second, we could turn to community land trusts. A nonprofit organization owns the land on behalf of a local community, and either develops the land itself or leases it to developers. Essentially, you're removing the land the from being traded on the market. George himself actually concluded that, given land's unique nature, private ownership of it makes no sense. (Bernie Sanders has been a big promoter of this idea too.)

But third, and most importantly, is the best idea, and something else George suggested: a land value tax.

You just tax the land. Not the property or anything else on it. Just the dirt itself.

Because the value of the land exists completely independent of individual human effort, you can't discourage economic activity by taxing it. (If you tax property, you risk discouraging people from improving their property.) This means the tax rate can be super high with no efficiency cost.

In fact, a land value tax would encourage economic activity, by creating a "use it or lose it" scenario. Land owners need to develop their land as furiously as possible, and build as much housing as possible, to bring in enough income to stay ahead of the tax. Or give it up to someone who will. The tax prevents land speculation. You wouldn't necessarily get that same pressure for development with a community land trust.

A land value tax at the federal level would probably also create a lot of nascent political pressure within localities to liberalize zoning laws: The tax would push developers to push for more freedom.

Finally, it would combat inequality. Thomas Piketty argued that income from wealth tends to overtake income from labor over the long term, driving inequality ever higher. But it turns out housing costs are the cause: Take them out, and wealth income stops overtaking labor income. On the flip side, people bidding for land that's in demand is what drives the price up. If the sky's the limit on inequality, the sky's the limit on land prices. By having the government siphon off the value of the land itself, you prevent it from going to individual owners and driving the inequality ratchet further upward.

Then you could pour the revenue into public works and job creation, or big universalist aid programs. Hell, since the value of the land is the ecological result of our collective economic activity, just give the revenue back in equal per capita checks to everyone.

Land represents a unique quirk in the basic engine of human economic activity. But we have tools for addressing it. Tax the dirt!

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinics

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinicsUnder The Radar Giorgia Meloni scores a political 'victory' but will it make much difference in practice?

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

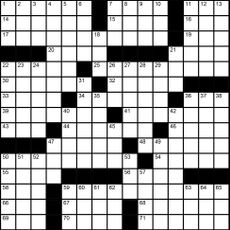

Magazine interactive crossword - May 3, 2024

Magazine interactive crossword - May 3, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - May 3, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Magazine solutions - May 3, 2024

Magazine solutions - May 3, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - May 3, 2024

By The Week US Published