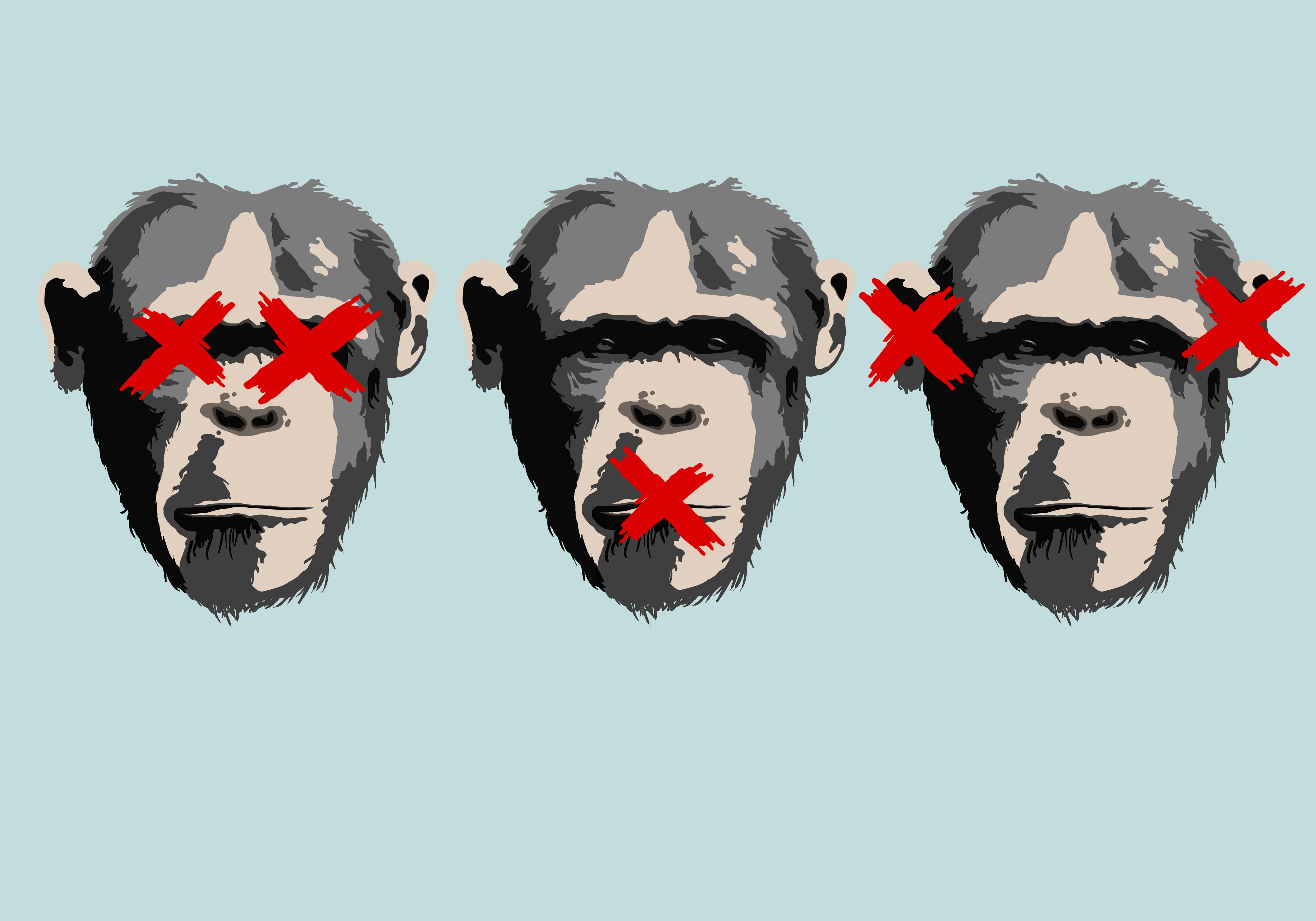

Ban jargon!

New evidence suggests that, more often than not, your beloved big words come up short

Dr. Bernard Lown knows firsthand about the inherent dangers of using jargon. One day, before he became a renowned cardiologist and won a Nobel Peace Prize, Lown was completing his medical fellowship when "Mrs. S" came in for her weekly treatment for a mild narrowing of a valve on the right side of her heart. She was, according to Lown, a "well-preserved" woman who, despite her heart condition, was able to keep up with her duties as a librarian, and with her housework.

As Lown and his fellow trainees examined the woman, another doctor who had been treating Mrs. S for a decade stopped by to greet her and then turned to the group and said, "This woman has T.S." Then she left.

Mrs. S immediately went pale and her heart started to race. Alarmed, Lown asked what was the matter. The patient replied that she knew "T.S." meant "terminal situation." Lown initially laughed at her misinterpretation of the acronym for tricuspid stenosis, the medical term for the heart condition she'd been living with for years relatively unfettered. But his bemusement transformed into concern as Mrs. S's lungs filled with fluid and her heart failure worsened. By the end of the day, she was dead.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This happened decades ago. And of course, it's an extreme example. Usually, jargon will not kill you. Still... we should all be wary of trotting out impenetrable terms when plain old English will suffice.

Jargon comes in lots of forms: medical language (as in the example above), weird acronyms (no doubt you've used "LOL," but have you heard of "ELI5"?), all-too-common office buzzwords (Synergy! Pivot! Growth hacking!). Indeed, we live in a world awash in jargon, and it's only getting worse. One recent survey found that the number of words in the English language grew from 544,000 words in 1900 to 1,022,000 in 2000. Many of these words debuted in academia and have since become mainstays in the classroom.

This is not a good thing. Here are a few reasons to consider banning jargon from your vocabulary, before somebody gets hurt (or at least completely misinterprets you when you tell them to "run it up the flagpole").

1. It could make you sound less professional

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

While it's tempting to use big words or technical acronyms to appear smarter and more experienced, one new study has found it might actually make you look worse. Researchers followed 53 doctors in training as they underwent an evaluation in which they would visit different test stations in a hospital. At each station, an actor pretending to be a patient with a particular problem, and a physician evaluator, rated how well the trainees addressed the medical scenario.

The results? Trainees who used big jargon terms were rated as less professional, both by the doctors and the actors pretending to be patients. More specifically, trainees who abstained from using jargon were rated around 9 percent more professional on average than those who used two jargon terms in the interaction. For trainees who used more than two jargon terms, "professionalism ratings dropped precipitously."

2. Opaque words often disguise deceit

A decade ago, when one survey asked 110 Stanford University undergraduates about their writing habits, 86 percent of the students copped to injecting complicated language into their essays to make themselves sound more intelligent. And those are just the students who admitted to doing so. Then, late last year, researchers uncovered something a bit more sinister. They looked at 253 papers retracted for fraudulent activity such as faking or manipulating data, and compared those to unretracted papers, as well as studies retracted for reasons other than fraud (such as ethical violations or authorship issues). The analysis found that fraudulent papers had about 60 more jargon-like words, on average, than unretracted papers. It seems people aren't just using technical terms to look smarter. They may use them to cover-up their own inaccuracies, too.

3. Jargon is tarnishing the English language

Jargon disempowers and alienates the general public. Why deploy the financial term "disintermediate" — a mouthful — when you can use the more digestible (if tired) phrase "cut out the middle man"? Likewise, the impossibly long word "pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism" is more easily understood by a non-specialist when it's described as a medical condition that can cause bone defects. We're degrading communication when we stuff our sentences with overwrought terms. As Winston Churchill once said, "Short words are best, and old words when short are the best of all."

Is there a time and a place for big words? Yes, certainly. But if you must use them, introduce them only after you clearly convey the concepts they describe. That's the message from a study published earlier this year in which researchers tracked two sections of an undergraduate biology class at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. One section received the regular reading assignment, while the other received a similar reading assignment with complicated genetics terms swapped out with jargon-free substitutes.

When both sections attended the in-person lecture for the course, they were exposed to the jargon terms throughout and later given an in-class test. The results are intriguing: The students who received the concepts-first reading assignments answered questions about the genome correctly more than twice as often as those who read the jargon-laden texts before class. Such data gives us an inkling of how useful it can be to hold off on introducing jargon until the time is ripe.

Teachers and practitioners of medicine are arguably some of the worst culprits of using technical jargon. But this emerging data should speak to us all. Educators who use jargon without taking the time to explain the underlying concepts first risk leaving students behind as they charge through the lesson plan using unfamiliar terms. And those who develop a habit of excessive jargon use may find they are unable to connect with others.

Ultimately, none of us want our interlocution to preclude cognitive processing in the cerebral cortex. In other words, we all want to be understood.

Roxanne Khamsi is a journalist and educator based in New York City. She is chief news editor for the biomedical research journal Nature Medicine and a lecturer at the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University.