Why I'll never cheer for my son

Parents, please: Let's all agree to stop cheering, prodding, and meddling at our kids' games

A 9-year-old boy kicks at the pitcher's mound in the late innings of a Little League baseball game. His team, which includes my son — presently at shortstop, and getting antsy — is losing by an insurmountable margin. Yet the pitcher's father is on the edge of his canvas chair, screaming as though his life savings are on the line.

"Ethan! RELAX!" Then lower, more strained: "Stop looking over here!"

Ethan absorbs this advice, turns, winds up, and sails one over the catcher's head. The sound of ball against chainlink backstop has barely faded when this dad — trying a contradictory strategy — yells, "Ethan! FOCUS!" And then, of course: "Why are you looking over here?"

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This is a scene that, with minor variations, I've witnessed repeatedly throughout my son's 2018 season, which has been notable for both a leap in the children's skill and the games' subsequent transformation from pleasantly numbing affairs to contests of life and death. The kids can hit and catch, and there are expectations now. The dugout, once a place for goofing off, is where they now chew sunflower seeds to settle their nerves and chant like Nordic oarsmen. When they strike out or make an error — which is often — a few of them use the dugout as a place to crumple and weep. This is not to say that they aren't having fun, at least most of the time — but when they succeed, they radiate more relief than joy.

The stakes have been raised, and it isn't the ballplayers' doing. They've been raised by the adults on the sidelines, many of whom spend significant portions of each game thumbing through their phones. When others' kids are up, they're on Instagram, but when theirs is at the plate, they're on their feet, documenting the at-bat and faithfully giving Mark Zuckerberg the content that he craves. While teaching the child social media's primary lesson — nobody matters but you, right this second — the pressure on him or her, watching the pitcher as the camera watches them, ratchets up that much more.

After these at-bats, before returning to their phones or IRL chats, the mothers and fathers cajole and encourage and praise excessively, even in failure. Especially in failure. Good job, Jude! one says to a kid who has languidly whiffed on three balls in the dirt. Good cut, buddy! The adults, feeling a tremulous anxiety, pass it to their offspring as if through DNA. I'm nervous, they're saying. Let me scream and make you nervous too.

I'm not exempt from such nervousness — on the contrary, when my son pitches, I feel like I'm being wheeled into surgery — but I stay quiet, thanks to an NPR interview I heard in 2015, when St. Louis Cardinals manager Mike Matheny was promoting The Matheny Manifesto: A Young Manager's Views on Success in Sports and Life. In the interview, he spoke of his experiences coaching Little League, and what he'd told his players' parents:

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

[D]uring the game, do whatever you could just to take yourself out of the picture. The kids don't necessarily need you to be yelling words of encouragement at the top of your lungs. And this is really coming from a number of studies where they go and they interview collegiate, high school, and even lower-level athletes and asking them, 'What do you want your parents to do at the game?' And the overwhelming answer is absolutely nothing. And it comes back to: What's the goal? This is about the kid. This is not about the parents. [Mike Matheny]

Matheny went on to describe a young athlete's mindset:

[Y]ou're trying to please your teammates. You're trying to please your coach. And then you got the most important person in your world back there screaming at you, and you think, 'If I don't get this done, I disappoint them.' And that's when you get to the point where these kids just check out. And they say, 'Listen, I just can't get this thing right. I might as well go back to my room and play some videogames where nobody bothers me.' [Mike Matheny]

I was struck by this; on its face, it seems almost monstrous to withhold your cheers, an offense that, decades later, would seep out in therapy: He just sat there, my son would say, his voice wavering. He never said a thing. But then I remembered my own playing days: the exhilarating nausea of standing in the box, fighting the voices that insisted I'd strike out or get a hit. Maybe Matheny was right: Why add another voice? So when my son started tee ball, I said nothing when he came to bat. At first, it felt malicious; for God's sake, other parents were rooting for him. But he never reacted or complained, and seemed happy after every game. Three seasons later, I'm still mute: I don't tell him that he "can do it," call his name, or commend his "good job" when he does the opposite. And though it might be coincidental, when he fails — which in baseball is most of the time, even for the best players — he's unfazed. He smiles shyly, pounds his glove, and gets ready for what's next.

My fellow Little League parents and I are raising children at a fraught moment: When our kids emerge from their hideously expensive colleges, they'll battle hordes of sentient, Chinese-built robots for a dwindling number of low-paying jobs (or so I'm told). So we push them into Little League, guitar lessons, acting classes — anything that might allow them to escape the worst of our dystopian future.

But we want their success so fervently that we've lost the perspective and emotional means to make it possible. We meddle, prod, and mess with their little heads in the name of a scattershot and desperate love. We sit in foul ground, Apple products in hand, and scream for a strike or a hit as if it matters. And when they collapse and cry after Bucknering a grounder, we hustle over and console them, phones now at our sides. After all, we don't post photos of their tears; we need to steer them toward happiness, as we suspect that that's our job. We kneel and say: Hey, it took a tough hop, kiddo. It happens. And then, almost by accident, we stumble upon the right words: It's okay. It's just a game.

Jacob Lambert is the art director of TheWeek.com. He was previously an editor at MAD magazine, and has written and illustrated for The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Weekly, and The Millions.

-

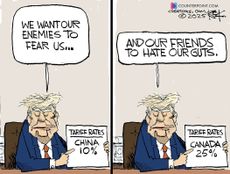

Today's political cartoons - February 4, 2025

Today's political cartoons - February 4, 2025Cartoons Tuesday's cartoons - friends and enemies, DEI in DC, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Things Donald Trump has said about women

Things Donald Trump has said about womenIn Depth The president has a long history of controversial remarks about the opposite sex

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

The safety of air travel in the 21st century

The safety of air travel in the 21st centuryThe Explainer Recent accidents have shaken faith in flying for some but commercial jets remain one of the safest modes of transport

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published