It's so much more than cooking

The mental load of food prep is heavy — and women often are the ones to carry it

Picture the inside of your fridge — stuffed or bare, messy or clean. Without actually looking inside, name three foods that you know are in there. (Off the top of my head: eggs, Little Gem lettuce, and pre-shredded cheddar cheese.)

Think about how much of each item you have. (A dozen plus three, about half a head, one unopened bag.) Think about when they were purchased, and how soon you'll need to use them before they go bad. (The eggs are all right — I bought them a couple weeks ago. The lettuce needs to get used before the weekend, for sure. The cheese … it's unopened, but I don't remember when I bought it. What's the sell-by date?)

Think about what meals you might be able to make with each of those ingredients. Think about how many portions those meals will make, and how long the leftovers will keep. Think about what other ingredients you'd need to acquire in order to make those meals. Think about how much those ingredients cost, and how much money you have available to buy them. Think about who else will be eating with you, and what they do or don't like, and what they can or can't eat. Think about how long it'll take to cook. (How long until mealtime? How hungry am I? How hungry is everyone else?) Think about the inevitable sink full of dishes, and who will do them, and how long after the meal they'll get done. Think about doing this all over again every time you cook.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Feeding ourselves and others involves an awful lot of work. Even in our food-obsessed American culture — where recipes go viral on social media, and people watch other people cooking on TV for fun — much of that work is explicitly rendered invisible. We talk about recipes, and eating, and sometimes about cleanup, but we don't discuss all of the other labor, both physical and mental, that's bundled into the single word "cooking."

As an avid home cook, I get great pleasure out of turning raw ingredients into delicious and nourishing food. I love planning elaborate centerpiece meals, or making something quick and tasty out of whatever's in the fridge. By choice, and also out of habit, I've taken on nearly all of the food prep in my household. I elbow everyone else out of the kitchen, or backseat-cook over their shoulders. I'd long assumed that I was getting more out of it than I was putting in.

Then, about a year ago, I had a sobbing meltdown in the kitchen in front of my spouse. It had started out innocently enough: He'd invited a friend over for dinner, but I was on a high-pressure work deadline and had no time or mental energy to spare. "I'll make dinner!" he said. "You don't have to do a thing."

That evening, he waltzed through the door from work, bubbling with enthusiasm. I met him in the kitchen, exhausted and hungry. "Okay, I'm ready to start cooking," he said. "What do we have in the fridge?”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I stared at him for a moment, and felt myself crumple in frustration. The strength of my reaction to this question surprised even me. Why on Earth was I so upset? It took some deep breaths, and a bit of damage control that evening, and a number of halting, stumbling conversations over the course of the next few months, but eventually I put my finger on it.

In offering to make dinner, my husband, with the absolute best of intentions, had focused on the one thing he'd promised to do: grab a pot and a pan, put something in it, and make edible food. But what I'd wanted him to do was much more complex, so ingrained in my experience of cooking that I didn't even think to articulate it. I wanted him to pick up the baton. To check what ingredients we already had, and what might need using up. To plan out a meal that would meet everyone's dietary needs and preferences (including a balanced amount of protein and starch, and at least one vegetable). I wanted him to look up recipes, and make a grocery list if needed, and stop by the store on the way home. I wanted him to make food appear without my having to think about it.

I wanted him to make dinner. And it hadn't even occurred to him to look in the fridge before he left for work that morning. This wasn't entirely his fault: I realized that he didn't want to guess at the cooking process on his own because I had so thoroughly claimed my title as the keeper of the food.

For those of us who cook frequently, planning and strategizing for meals becomes background noise. It's part of the mental load, the running list of small decisions and knowledge required to maintain a household. And as with so much of that mental load, cisgender women like me end up shouldering the lion's share. We are trained to reflexively and uncomplainingly take on as much of the mental load as we can possibly bear. And cooking is still a highly feminized pursuit; it's a skill girls are implicitly expected not only to learn, but enjoy doing. To be feminine, we are told, we must be hospitable, nurturing, giving — qualities that are intimately bound up with feeding those around us. If a meal isn't balanced and complete, if someone isn't happy with their portion, if it costs too much or doesn't land on the table on time, it feels like a personal failure.

Of course, I know plenty of cis women who have little or no interest in cooking, and a smaller number of cis men who happily take on food prep duties for their entire households. But when I hear a woman admit that she doesn't cook, it's usually with embarrassment or shame in her voice; when I hear a man say that he cooks for his family, it's a point of pride, a marker of going above and beyond.

Because women are expected to know how to cook by the time we reach adulthood, we tend to be better, or at least more practiced, at it than our male partners. When you're better at something, it seems only natural that you be the one to do most of it. And if you're doing the cooking, then it's only natural that you do all the other associated labor too. Because we have no separate name for that labor — it's all just "cooking" — those who have internalized the mental load define it one way, and those who have been allowed to dabble see it very differently.

When my husband volunteered to do the cooking that evening, I thought he was allowing me to free up some of my cognitive resources, so that I could apply them elsewhere. He thought he was just in for a bit of manual labor. We were speaking different languages.

As far as straight cis marriages go, mine is pretty darn egalitarian. I'm proud of that. And yet, when it comes to food prep, we've slid neatly into our societally-defined roles: me as the boss of the kitchen, and my husband as the person who takes directions and otherwise stays out of my way. I'm the one who remembers which of our loved ones is allergic to black pepper, which store stocks the brand of pretzels he likes, how long ago we bought that jar of peanut butter. But neither of us had realized the mental toll of this dynamic, until that evening.

I'd love to say that was the last time we had this particular argument — that we've hashed it all out now. But the mental load of food prep is still lopsided in our house. I still like to cook more than my husband does; I'm still the keeper of what's in the fridge. But at least now we can recognize and name the forces at work — just one more step towards balance on our literal and metaphorical plates.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Zoe Fenson is a freelance writer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her writing has appeared in Longreads, Narratively, The New Republic, and elsewhere. When she's not writing, you'll find her doing crossword puzzles in cocktail bars or playing fetch with her cat.

-

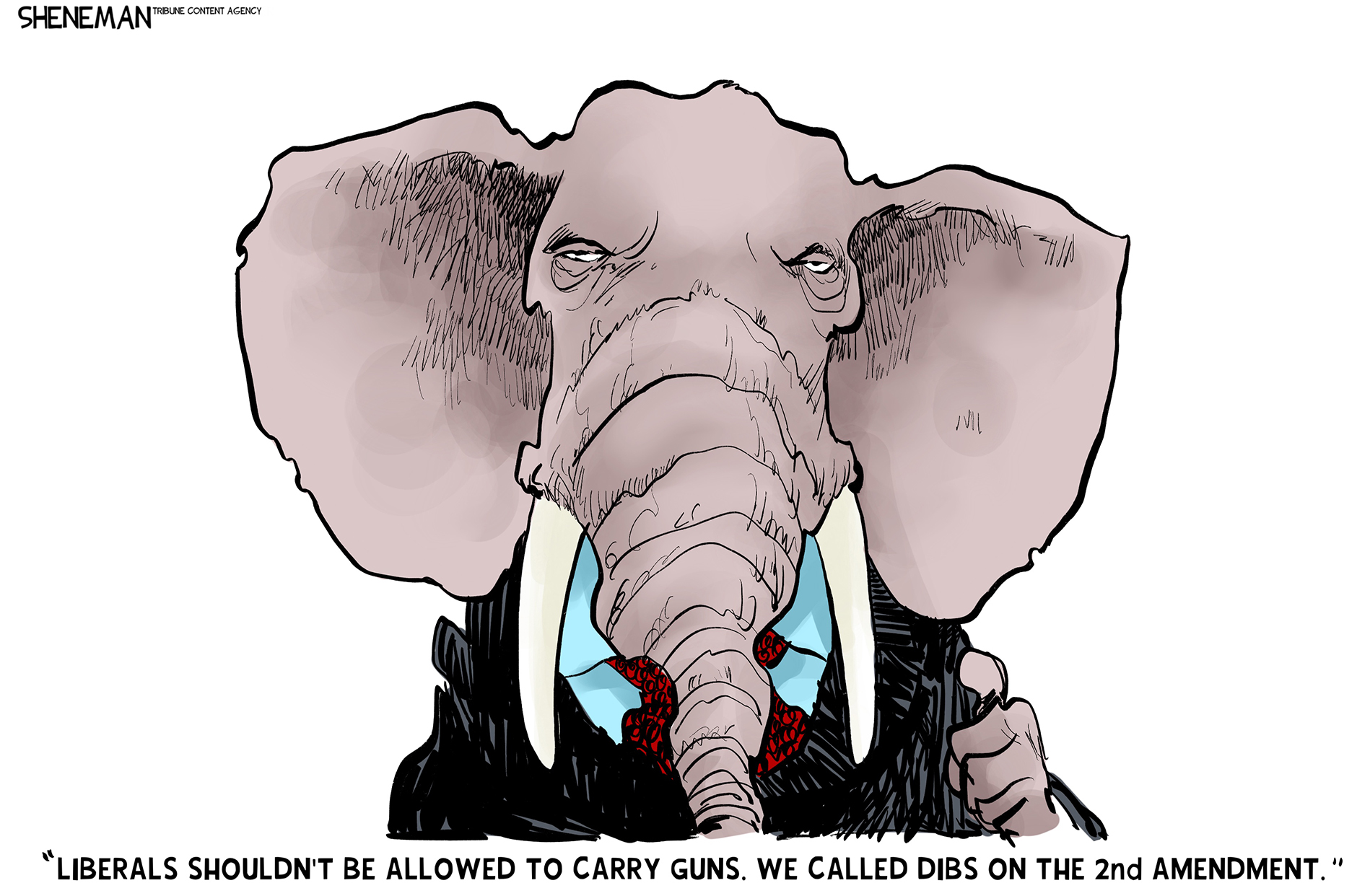

Political cartoons for January 29

Political cartoons for January 29Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include 2nd amendment dibs, disturbing news, and AI-inflated bills

-

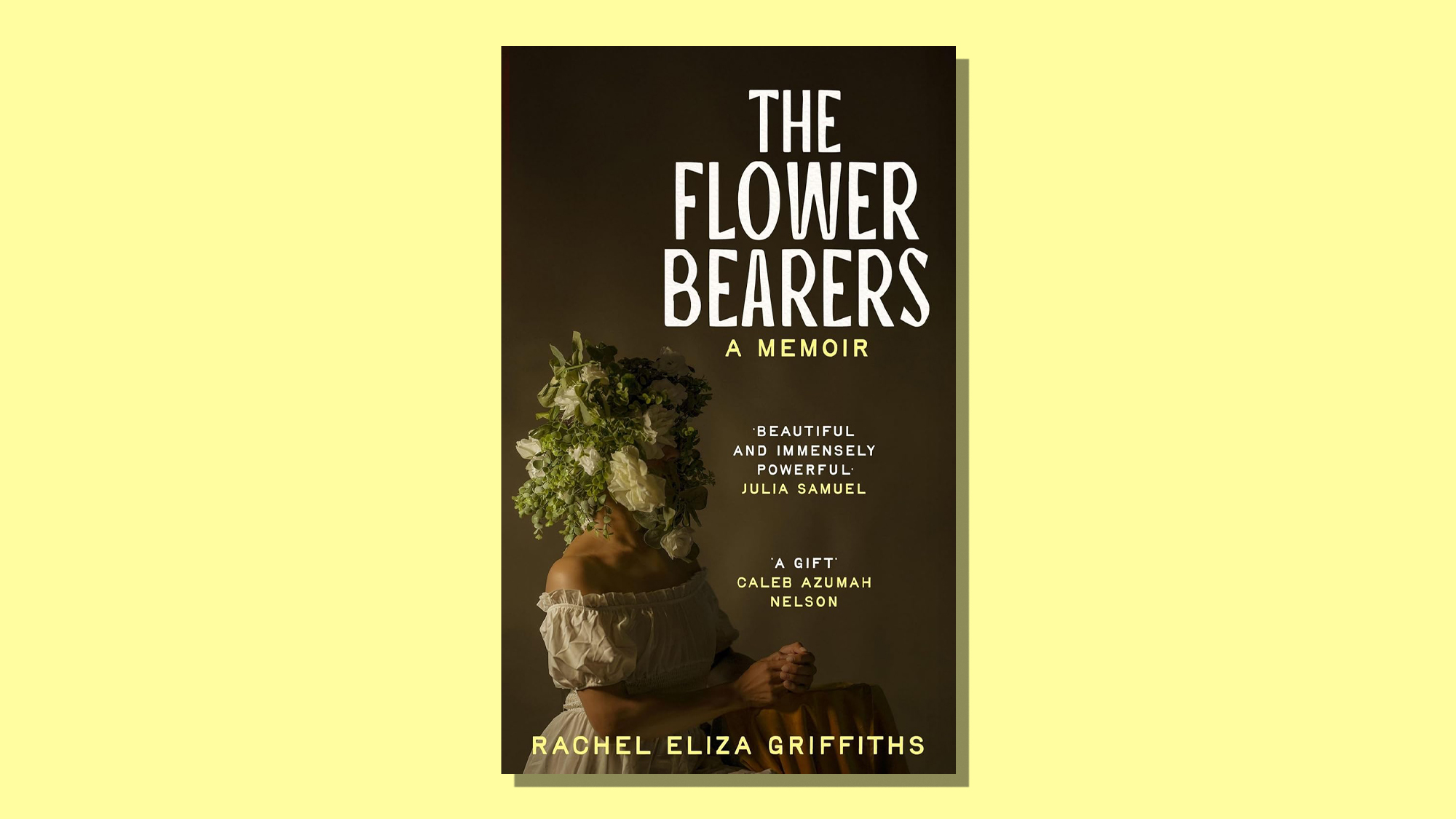

The Flower Bearers: ‘a visceral depiction of violence, loss and emotional destruction’

The Flower Bearers: ‘a visceral depiction of violence, loss and emotional destruction’The Week Recommends Rachel Eliza Griffiths’ ‘open wound of a memoir’ is also a powerful ‘love story’ and a ‘portrait of sisterhood’

-

Steal: ‘glossy’ Amazon Prime thriller starring Sophie Turner

Steal: ‘glossy’ Amazon Prime thriller starring Sophie TurnerThe Week Recommends The Game of Thrones alumna dazzles as a ‘disillusioned twentysomething’ whose life takes a dramatic turn during a financial heist