Tengri: the brand making Mongolian yak yarn fashionable

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

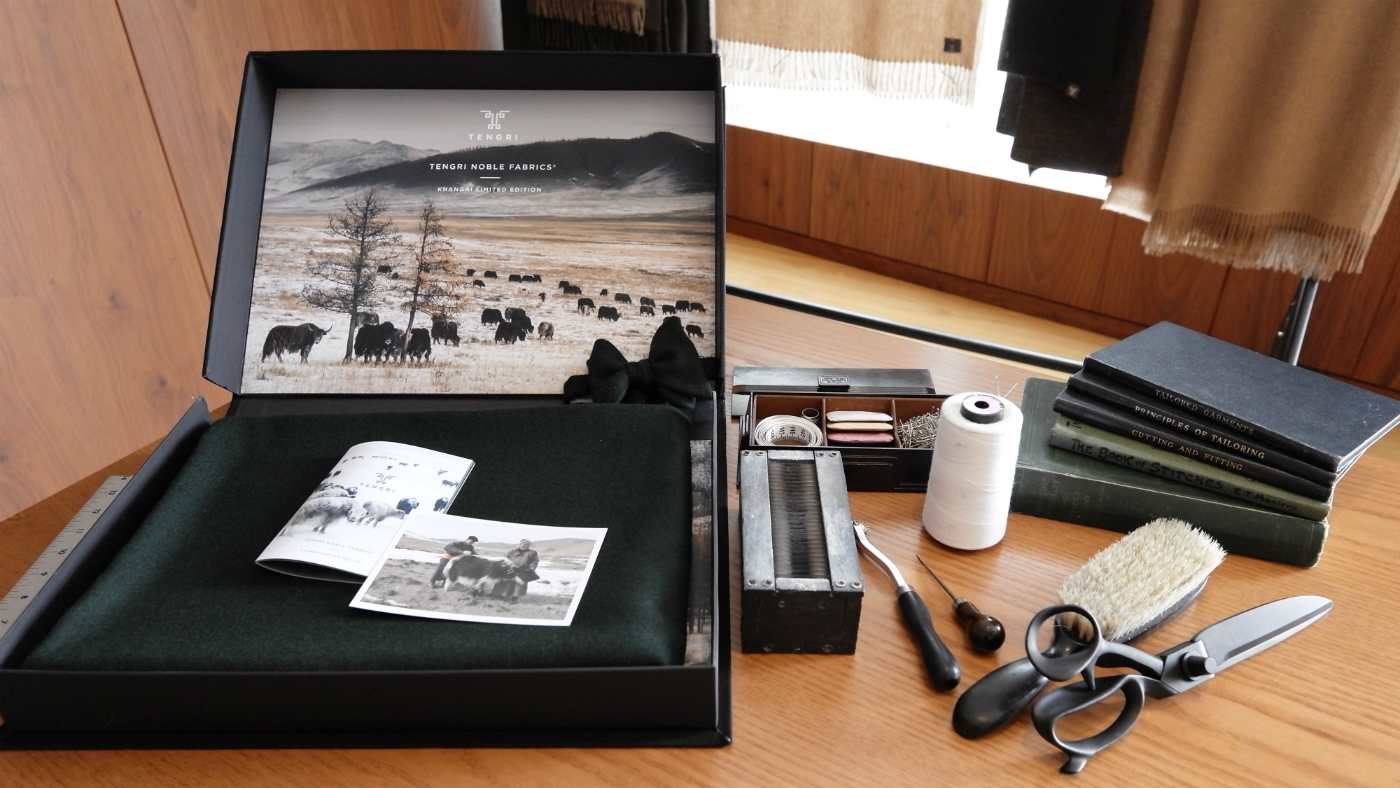

From the nomadic herder families of Mongolia to the most exclusive stores in London, Nancy Johnston’s Tengri fashion label aims to champion sustainability, respect for the natural environment and fair trade.

The Week Portfolio caught up with Johnston to find out how she is making Mongolian yak yarn fashionable.

What is it about Mongolia that inspired you to start your business?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Travelling to Mongolia was a lifelong dream I had carried for 20 years. The vast landscapes, the nomadic herders’ way of life, the strength and self-reliance of the Mongolian people (young and old) living off the land and animals in such a remote and isolated place – all this captivated me.

In 2013 I took my first visit, with no agenda other than to explore, and my experience there led to the birth of Tengri! I lived with a yak herder family in the remote Khangai region and saw first-hand the challenges they faced. The family were desperately trying to save money for their young daughter’s education, but many of their animals had died due to a combination of land desertification and a prolonged winter.

Critically, what I discovered was that the nomadic way of life and future of wild animals are threatened by rapid industrialisation and desertification of the land, largely due to the intensive grazing of cashmere goats, which contributes to climate change. Nomadic herder families in Mongolia supply the world’s top fashion brands with luxury fibres – contributing to the €9 billion global cashmere market. But many nomadic herder families live on subsistence wages of around £1 per day.

What are the specific harms being done by the fashion industry that you are hoping to address? And where exactly does Tengri fit into the equation?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As we are all increasingly aware, after oil, the fashion industry is the second-largest polluter of the environment. This has a dire impact on land, sea, people and wildlife – and this is where we come in.

According to the United Nations Development Programme, as much as 90% of Mongolia is fragile dry-land, under constant threat of increasing desertification. Conservation biologists have found that unsustainable levels of grazing by cashmere goats and other environmentally damaging livestock have consumed up to 95% of forage across the Tibetan plateau, Mongolia and northern India, leaving just 5% for wild animals to graze. It’s no coincidence that in the last 70 years, temperatures have risen almost three times faster in this region than the global average.

Over 40% of Mongolia’s three million people depend on herding. Nomadic herders in Mongolia maintain the traditional lifestyle of their ancestors, moving between four seasonal rangelands to provide good pastures for their livestock throughout the year. This method of livestock keeping is in symbiosis with the fragile ecological environment of grasslands in the Central Asian Plateau. Having collective organisation enables herders to establish a land-use agreement with local government, protect their traditional user rights and become stewards of the land.

Tengri enables 100% transparent supply chains that cause no environmental harm and create positive social impact. We work directly with co-operatives representing over 4,500 nomadic herder families in the Khangai region of Mongolia, ensuring they receive a fair-share income whilst establishing herder land rights.

How can yak fibres help? And what, exactly, defines a noble yarn?

Yak is a sustainable alternative to cashmere. When they graze, yaks eat just the top of the grass, promoting biodiversity and sustainability. This is very different to the way non-indigenous cashmere goats eat – they rip out the grassroots, damaging the land and contributing to desertification.

In Mongolia, the Khangai yak roam semi-wild, often at high altitudes, and endure extreme summers and harsh winter conditions. This means their coats are a robust and unique natural material, with textures and colours found only in animals native to this region, where they graze on mineral-rich terrain.

Noble fibres is a term used in the textile industry to describe fibres sourced from rare animals. When spun into a ‘noble yarn’, it is so named for its rarity, superior quality and performance. In Mongolia, I discovered the amazing properties of a rare breed of Khangai yak that produces the softest yak fibres on the market. We produce Khangai noble yarns which are as soft as cashmere, warmer than merino wool, hypoallergenic, resistant to water and odours, and more resistant to pilling than other luxury fibres.

Are the problems connected to fashion consumer-led or industry-led? To what extent do individuals have to think about their own relationship with clothes?

It has to start with the industry, but we need to remember that consumer purchasing power is a powerful tool and collectively it can create the widespread industry change that is needed.

How is it to work alongside nomadic herders from Mongolia? Are you able to exchange business expertise?

I’m really proud to arm the herders in Mongolia with market insight, empower them with business expertise and facilitate international trade.

At every stage of production, from the combing of fibres to the cleaning, de-hairing and up until the point of export, I work with all my partners in Mongolia to refine and develop a new business model and supply chain, based on trust, transparency and long-term partnership. This enables the much needed stability and economic security against fluctuating consumer trends and an uncertain global market. I’m really proud to have enabled the nomadic herders to be the first in Mongolia’s history to trade directly on the international market.

The name of your business references a Mongolian deity. How did you settle on this?

The word ‘Tengri’ means a pantheon of sky gods that govern human existence and natural phenomenon on earth. When you travel through Mongolia, you’re always under the endless blue skies and you see blue ribbons around trees, rocks and other spiritual places, honouring these deities.

I wanted the name of the company to reflect Mongolia and as a name, it just felt right. Tengri was also the name of my friend’s cat in Mongolia and I liked the meaning so much that I borrowed it! When I asked the nomadic families for their thoughts, they gave me their blessing and asked me to ensure that everything I do is done in the highest honour. I have done this to the best of human capabilities, ensuring nothing but the best at each stage of design and execution of the business and Tengri products.

There have been many serendipitous moments along my journey, some of which would not necessarily make logical or business sense, and much of it could not have been planned. I guess one could say that the heavens are looking down on me, for which I continue to be grateful. There is still a long way to go for Tengri, so I hope the divine support continues as my journey continues.

For more, visit tengri.co.uk