The Geneva Conventions explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

How the international community brought humanity to warfare

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world.

The Geneva Conventions in 60 seconds

The Geneva Conventions are a series of international treaties – four, to be precise – agreed by representatives of national governments between 1864 and 1949. Further protocols were added in 1977 and 2005.

The general purpose of the conventions is to ensure the humane treatment of captured or wounded combatants and civilians in wartime, protecting them from violence and other abuses, and to guarantee the safety of doctors, medics and nurses treating the wounded.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Taken as a whole, the conventions “help draw a line – as much as is possible within the context of wars and armed conflicts –between the humane treatment of armed forces, medical staff and civilians and unrestrained brutality against them”, explained History.com.

Today, 196 states are signatories to the Geneva Conventions. Transgressors can be prosecuted for violations in any signatory state, in accordance with the doctrine of universal jurisdiction. This holds that “some crimes, such as genocide, crimes against humanity, torture, and war crimes, are so exceptionally grave that they affect the fundamental interests of the international community,” said New York’s Cornell Law School.

How did it develop?

Geneva became a byword for humanitarianism by chance. Henry Dunant, a businessman from the city, was in northern Italy in 1859 when he witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Solferino. Thousands of wounded troops were left to suffer on the battlefield owing to a lack of organised care.

On his return to Geneva, Dunant wrote a memoir of his experiences called “A Memory of Solferino” in which he recalled attempting to organise makeshift hospitals and civilian nursing for the wounded on both sides. In the book, he called for the creation of a neutral agency to provide humanitarian aid in times of war, and for an international agreement to respect the protected status of such an agency.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

His first demand led to the foundation of the Red Cross in 1863. The following year, 12 European powers agreed to be bound by a new treaty, the First Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field.

Signatory states agreed not to attack hospitals or medical staff aiding the wounded under the Red Cross symbol, and to respect the principle of providing treatment to all combatants.

In 1906, a larger group of nations – 35 this time – ratified a second Geneva Convention, which “extended protections for those wounded or captured in battle as well as volunteer agencies and medical personnel tasked with treating, transporting and removing the wounded and killed”, said History.com.

However, the events of the First World War, during which millions of captured soldiers were held in prison camps, made it clear that more protections were needed for prisoners of war (POWs). This became the focus of the third convention, passed in 1929. It stipulates that POWs “be treated humanely, adequately housed and receive sufficient food, clothing and medical care”, explained the Red Cross.

The fourth convention, passed in 1949, was unusual in that it “contained little that had not been established in international law” before the Second World War, said Encyclopaedia Britannica. Nevertheless, “the disregard of humanitarian principles during the War made the restatement of its principles particularly important and timely,” the reference website added.

With Nazi atrocities fresh in the minds of the international community, this renewed treaty focused on protections for non-combatants in combat zones.

Two additional protocols added in 1977 attempted to reflect the emerging trend of brutal civil and non-state conflicts, specifically outlawing “collective punishment, torture, the taking of hostages, acts of terrorism, slavery, and ‘outrages on the personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment, rape, enforced prostitution and any form of indecent assault’”.

A final protocol, in 2005, introduced the religiously neutral symbol of the Red Crystal, which along with the Red Cross and Red Crescent is now a universal emblem of identification and protection in armed conflicts.

How did it change the world?

The influence of the Geneva Conventions is “reflected in the establishment of war-crimes tribunals for Yugoslavia (1993) and Rwanda (1994) and by the Rome Statute (1998), which created an International Criminal Court”, said Encyclopaedia Britannica.

However, in the modern era, when many conflicts involve non-state groups, some critics have argued that “rules of war” are increasingly irrelevant.

“Wars today are more numerous, complex, protracted and violent than before,” said Sydney-based think-tank the Lowy Institute. “They kill more civilians, and are harder to resolve. They involve more armed groups, and these groups are often radicalised and loosely structured, making them hard to deal with.”

In 2014, against the backdrop of the vicious civil war in Syria, David Cameron warned that “the norms and laws” of humane conduct codified in the Geneva Conventions were “being lost”.

But the conventions’ central idea “that even wars have limits” continues to resonate, even in the most brutal combat zones, argued Dr Helen Durham, director of international law and policy at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

“Every day we see the law in action: when a military takes care in its targeting to not fire on civilian buildings, when a wounded person is allowed through a checkpoint, when a child on the frontlines receives food and other humanitarian aid, and when the living conditions of detainees are improved,” she wrote in an article on the ICRC website in 2019.

Evidence indicates there are “actually only a handful of places around the world where the Geneva Conventions aren’t being observed”, reported German newspaper Deutsche Welle.

But the debate has been renewed as the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, which began in 2022, draws on. Russia has been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity for “attacking civilian infrastructure such as power stations and dams”, BBC reported. There are also “credible allegations” of ill treatment of POWs on behalf of both Ukraine and Russia, according to head of the United Nations Human Rights Mission in Ukraine Matilda Bogner. “The prohibition of torture and ill-treatment is absolute, even – indeed especially – in times of armed conflict,” Bogner added.

Rebecca Messina is the deputy editor of The Week's UK digital team. She first joined The Week in 2015 as an editorial assistant, later becoming a staff writer and then deputy news editor, and was also a founding panellist on "The Week Unwrapped" podcast. In 2019, she became digital editor on lifestyle magazines in Bristol, in which role she oversaw the launch of interiors website YourHomeStyle.uk, before returning to The Week in 2024.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Music explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

Music explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth This emotive but hard-to-define art form has played a pivotal role in human evolution

-

Vegetarianism explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

Vegetarianism explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth How meat-free diets went from religious abstention to global sustainability trend

-

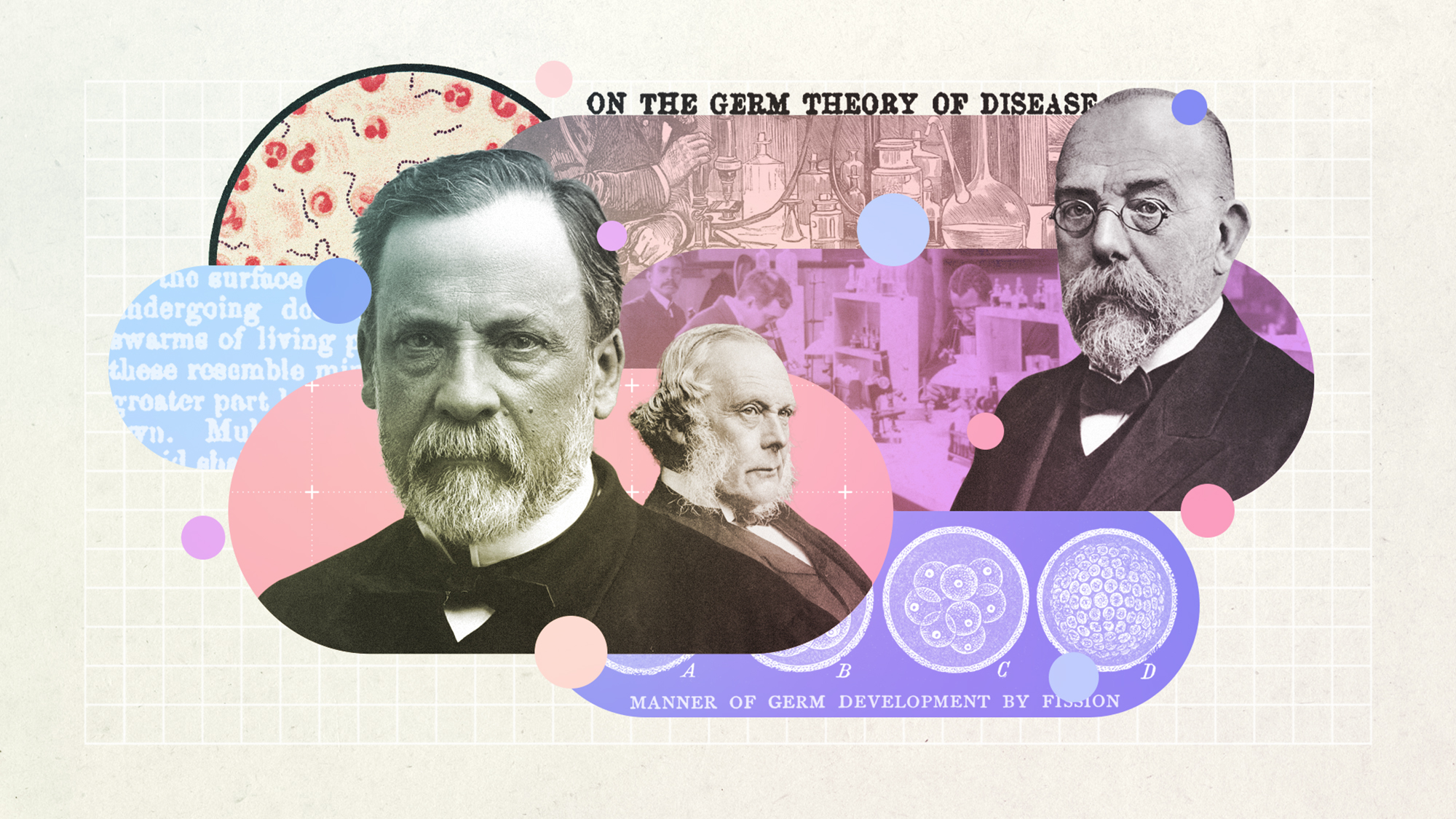

Germ theory in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

Germ theory in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth How a new understanding of bacteria revolutionised medicine

-

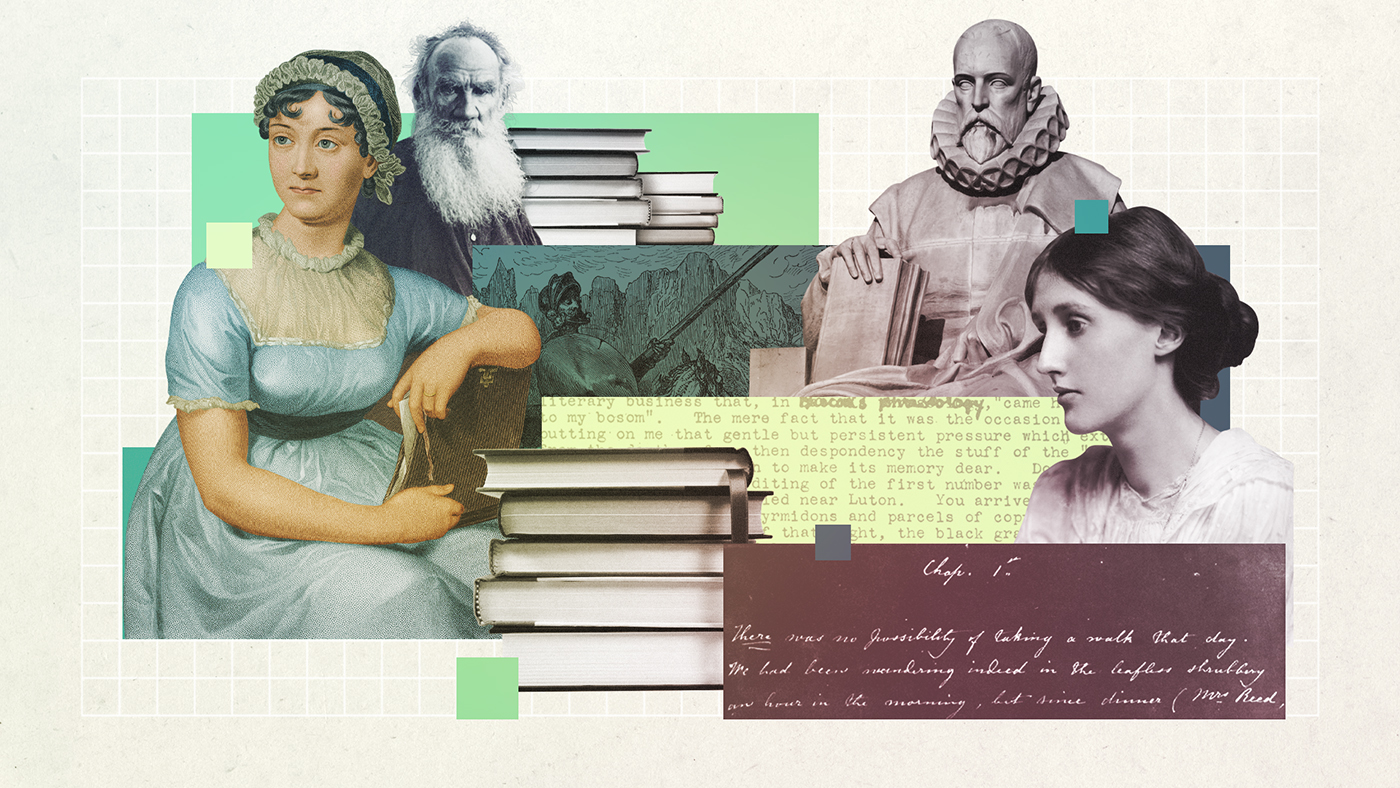

The novel explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

The novel explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth How a new way of portraying existence transformed literature

-

Fairtrade explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

Fairtrade explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth How paying farmers fairly went from niche to necessary

-

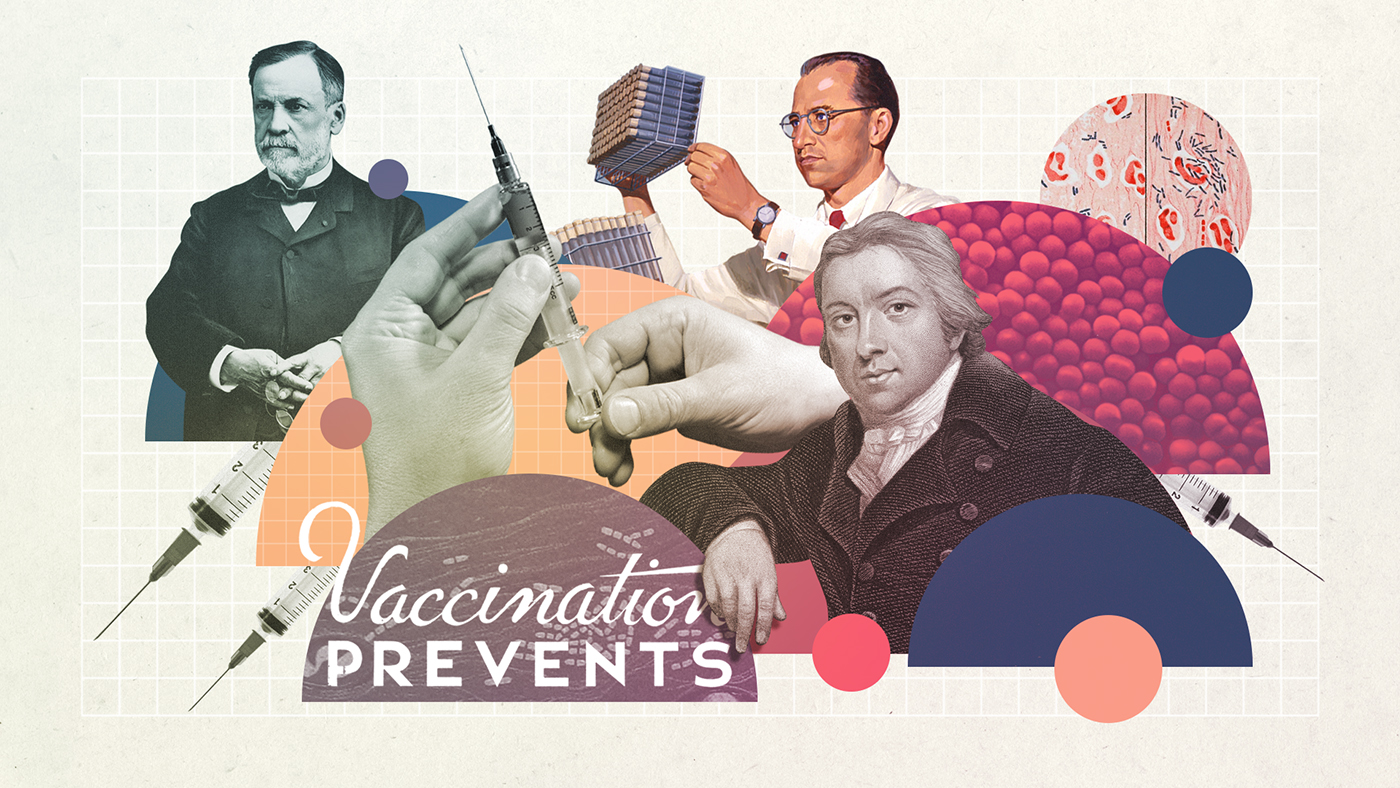

Vaccination explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

Vaccination explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth How a medical breakthrough has saved countless millions of lives

-

Feminism explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

Feminism explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth How women fought for social and political liberation

-

The printing press explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

The printing press explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the worldIn Depth How a German goldsmith revolutionised the way we share ideas