52 ideas that changed the world - 46. The unconscious mind

The theory of an obscured section of human consciousness has hooked psychologists for centuries

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world. This week, the spotlight is on the unconscious mind:

The unconscious mind in 60 seconds

The unconscious mind, often shortened to just “the unconscious”, refers to the processes that occur in the human mind automatically and that are not available for introspection.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This unconscious is the opposite of the “conscious mind”, a term that refers to the mental processing that we can think and talk about in a rational way, and that includes thought processes, memories, interests and motivations.

Saul McLeod, a psychology tutor and researcher at the University of Manchester, explains that the unconscious “comprises mental processes that are inaccessible to consciousness but that influence judgements, feelings, or behaviour”.

In an article on educational website Simply Psychology, McLeod says: “Our feelings, motives and decisions are actually powerfully influenced by our past experiences, and stored in the unconscious.”

And “while we are fully aware of what is going on in the conscious mind, we have no idea of what information is stored in the unconscious mind”, he adds.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

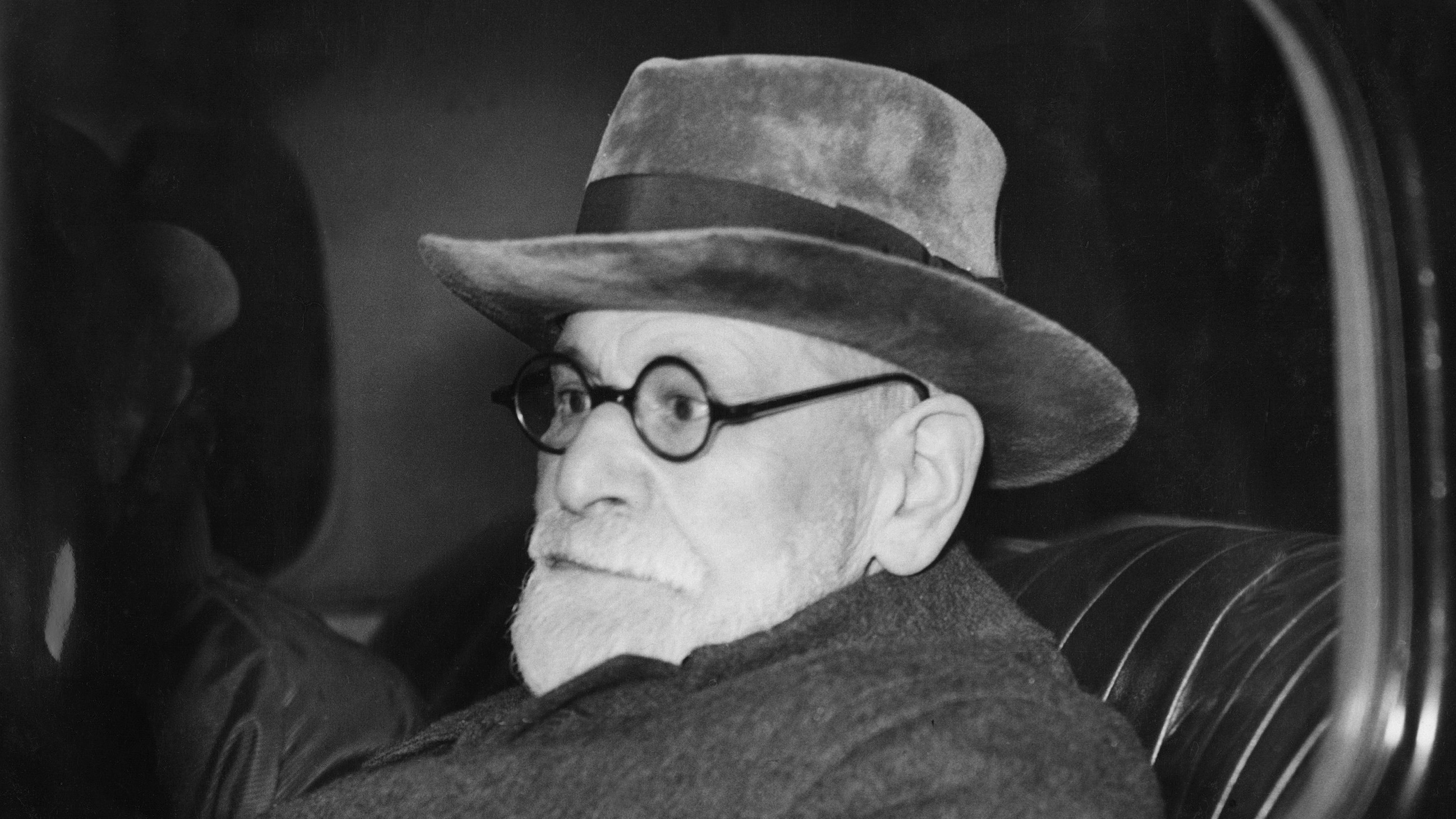

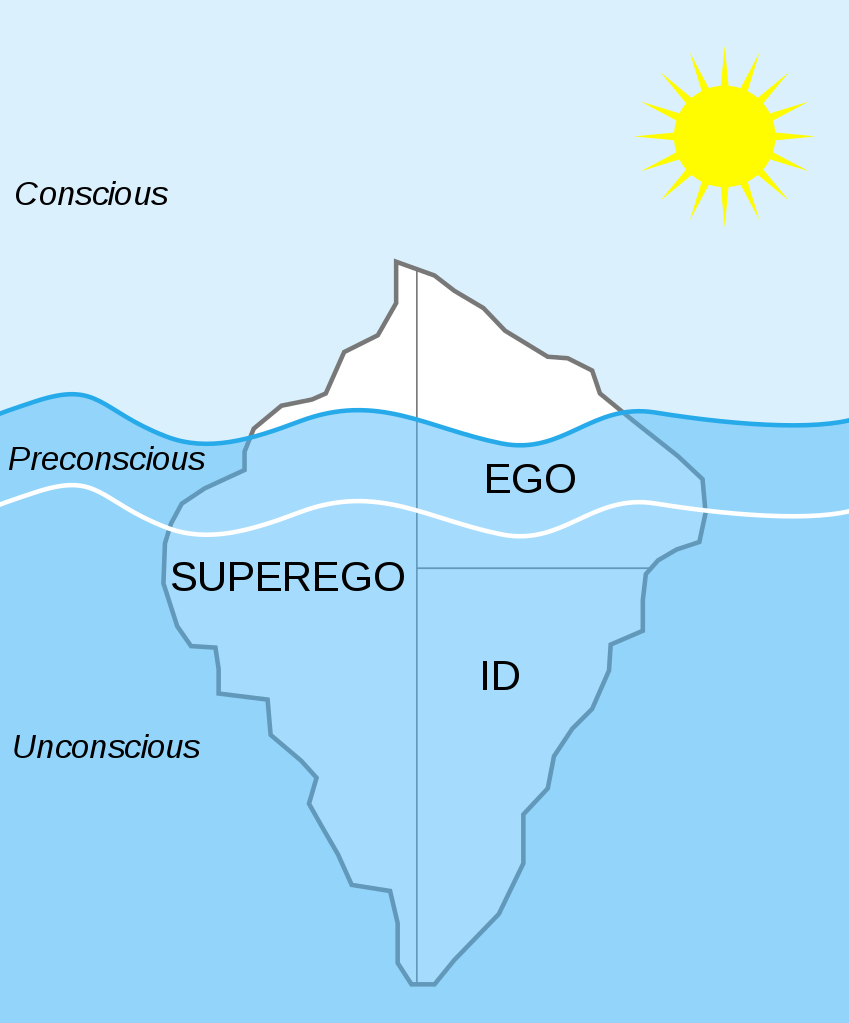

Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud,, the founder of psychoanalysis, compared the conscious and unconscious to an iceberg. In the analogy, the conscious is represented by the tip of the iceberg, while the unconscious is the bulk of the ice that is obscured underwater.

How did the concept develop?

The term was first coined by German Romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling, who in his 1800 book System of Transcendental Idealism talks about “das Unbewusste” - translated into English as “the unconscious” by Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

The concept fascinated Coleridge and he refers to it in his 1817 autobiographical work Biographia Literaria.

Coleridge wrote of the “conscious or unconscious… our only absolute Self”, an early description of what Freud would later term the “ego, id and superego” that together make up the human mind. The theory was quickly picked up by a variety of early psychologists.

In his seminal 1890 work The Principles of Psychology, American William James - who 15 years earlier had became the first educator to offer a psychology course in the US - examined how psychologists and other experts had used the term unconscious. James’ work drew on a range of 19th century writings by high-profile figures including German philosophers Arthur Schopenhauer and Eduard von Hartmann and French psychologist Pierre Janet.

In the early 1900s, Freud elaborated on theories of the unconscious and developed his model of psychic structure comprising id, ego and superego. Freud described the mind as having a vertical structure, with the conscious mind at the top, followed by the preconscious, and then the unconscious mind.

In his article on Simply Psychology, McLeod explains that, in Freud’s forumulation, “the unconscious mind is the primary source of human behaviour. Like an iceberg, the most important part of the mind is the part you cannot see.”

“The unconscious mind acts as a repository, a ‘cauldron’ of primitive wishes and impulse kept at bay and mediated by the preconscious area,” McLeod continues. “For example, Freud found that some events and desires were often too frightening or painful for his patients to acknowledge, and believed such information was locked away in the unconscious mind.”

Freud based his concept of the unconscious on a variety of observations. For example, he believed that “dreams and slips of the tongue were really concealed examples of unconscious content too threatening to be confronted directly”, says Encyclopedia Britannica.

Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung also developed an influential theory at around the same time. Jung agreed with Freud that the unconscious is a determinant of personality, but added that it is divided into two layers: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious.

The personal unconscious is a reservoir of material that was once conscious but that has been forgotten or suppressed, while the collective unconscious is an accumulation of inherited psychic structures, according to Jung.

The latter, Jung suggested, formed the “whole spiritual heritage of mankind’s evolution, born anew in the brain structure of every individual”.

The theory goes that this collective unconscious is “common to mankind as a whole and originating in the inherited structure of the brain”, Encyclopedia Britannica adds.

The overall concept of an unconscious mind has been critiqued, however, because it relies on experience, which cannot be directly observed by a psychologist or psychoanalysis. For this reason, the area of study has to be based on a degree of inference.

in an article for Psychology Today, David Feldman, associate professor of psychology at Santa Clara University, says that the “biggest problem” with Freud and Jung’s work is that it is “impossible to scientifically test”.

“As a general rule, scientists consider something true only when it can be meaningfully observed or measured,” Feldman says. “The unconscious mind, by definition, can’t be. After all, its central feature is that it’s completely inaccessible.”

The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones adds that for some critics, modern genetic research, “with its promise of directly connecting body and mind, seems to make Freud’s science of the psyche as insubstantial as, say, a belief in the healing power of crystals”.

How did it change the world?

As historian Mark Altschule notes, “it is difficult, or perhaps impossible, to find a 19th century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognise unconscious cerebration as not only real but of the highest importance”.

Freud’s work on the hidden elements of the human mind went on to influence theories about the origins of many so-called “neurotic symptoms”, which have been “held to depend on conflicts that have been removed from consciousness through a process called repression”, says Encyclopedia Britannica.

Research into the human consciousness also influenced fields beyong science; for example, inspiring the Surrealist art movement.

In an article on The Conversation, Natalya Lusty, associate professor of gender and cultural studies at the University of Sydney, explains how Freud’s work directly influenced the 1924 publication of the first Manifesto of Surrealism, written by French poet and theorist Andre Breton.

“The emergence of psychoanalysis and Freud’s theories of the mind offered surrealism a way to move beyond an empirical, surface apprehension of the world,” says Lusty.

“While Freud was interested in how everyday life informs dreams, the Surrealists experimented with the ways in which our dream world informs everyday experience, including creative practice.”

The idea of the unconscious has also been adopted more broadly as a way of understanding our thoughts and emotions. In 2014, the BBC reported that “75 years since the death of Sigmund Freud... the words and phrases he popularised are deeply ingrained in popular culture and everyday language”.

Listing terms popularised by psychologists researching the unconcious - for example, Oedipus complex and projection - the broadcaster adds that while modern science has begun to cool on the concept of the unconscious, its influence on our perception of the human mind lives on in everyday language.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. Zero

52 ideas that changed the world - 52. ZeroIn Depth The technology on which you’re reading this article only works because of zero

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. Money

52 ideas that changed the world - 50. MoneyIn Depth Millennia of civilisations have used mediums of exchange ranging from seashells and cows to bitcoin and cash

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. Ecology

52 ideas that changed the world - 49. EcologyIn Depth Scientific ecology can be traced back to Charles Darwin and considers living things and their environment

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. Relativity

52 ideas that changed the world - 47. RelativityIn Depth Einstein’s theory remains ‘most important in modern physics’

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. Writing

52 ideas that changed the world - 43. WritingIn Depth Writing is the foundation of history, great literature – and this article

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. Monogamy

52 ideas that changed the world - 42. MonogamyIn Depth The roots of monogamy have more to do with evolution than romance

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheel

52 ideas that changed the world - 41. The wheelIn Depth The wheel might seem simple, but it took humans a long time to figure it out

-

52 ideas that changed the world - 39. Selective breeding

52 ideas that changed the world - 39. Selective breedingIn Depth Domesticating animals and creating plants and crops allowed agriculture to flourish