A portrait of the artist: Meet Arabella Dorman

The society portrait painter tells us why she's as happy painting soldiers in Afghanistan as she is royals in Chelsea

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

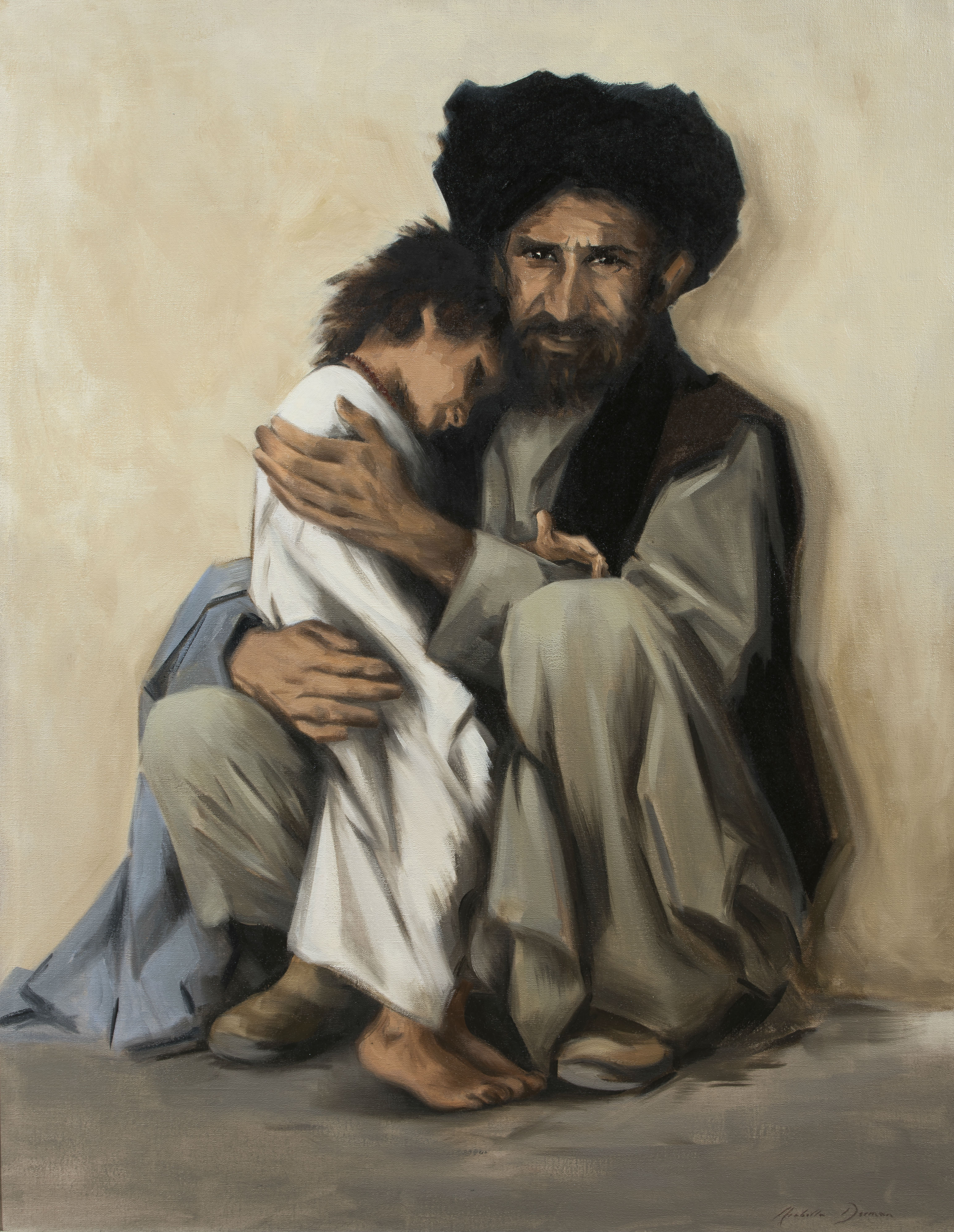

People fascinate portrait artist Arabella Dorman, whether they are members of London's high society posing in her Chelsea studio or British squaddies on the battlefields of Basra.

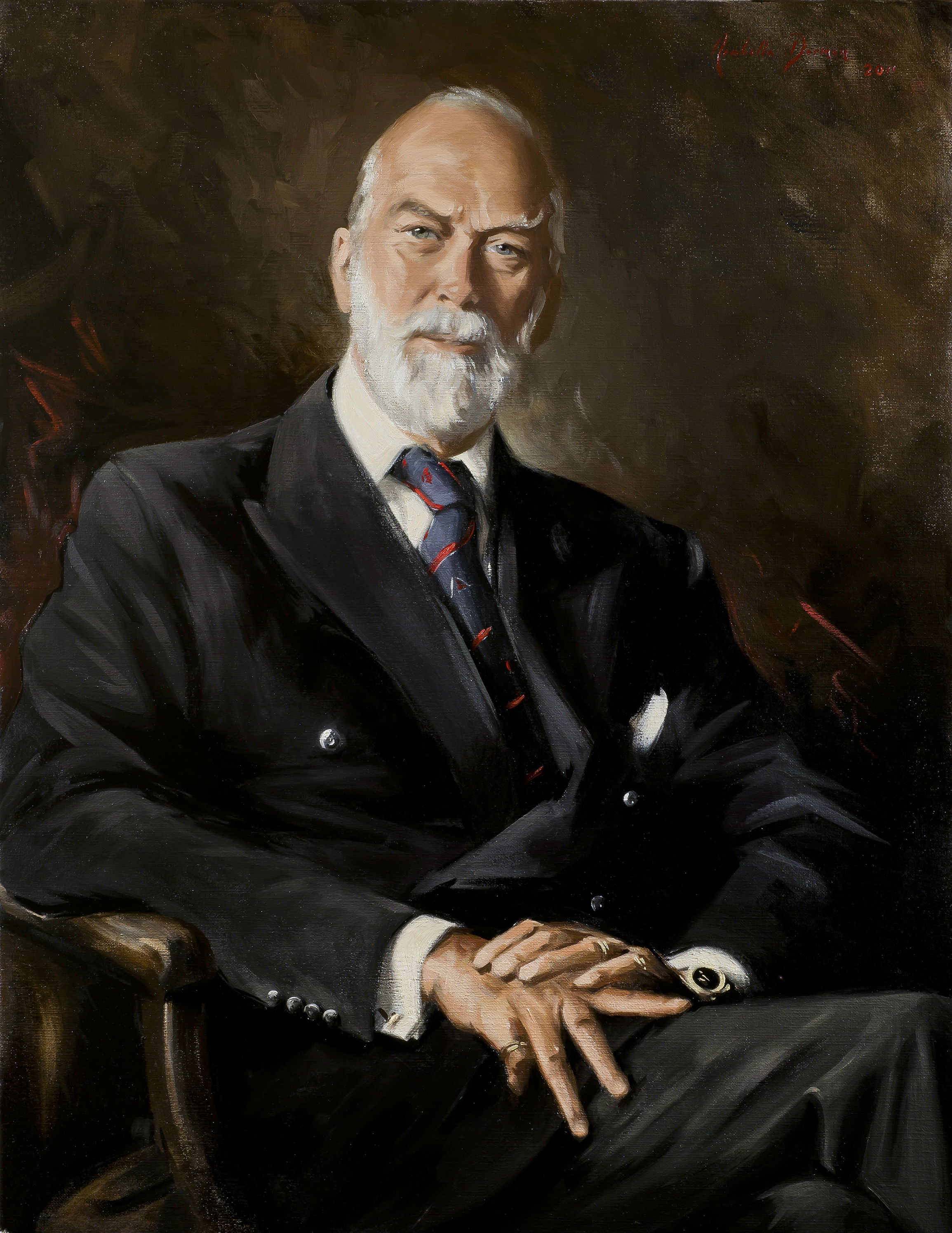

"On paper, they look worlds apart," she admits. "I'm this society portrait painter, painting royalty and extremely important people, moving between a portrait, for example, of Prince Michael of Kent to an Iraqi camp. But I don't see my war work and my portraits as incompatible. They're not that different."

It is hard to imagine Arabella out on the battlefields: tall and blonde, she looks made for the King's Road. Yet conflict and warfare has always intrigued her and when, in 2006, General Sir Richard Shirreff asked her to go to Iraq as the UK's war artist, she leapt at the chance – "with some apprehension, I must add".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

She spent a month in the war-torn country, travelling with the troops and painting all that she saw, even sketching under fire in Basra. So how did this elegant society artist, the granddaughter of Sir Maurice Dorman, a former governor-general of Malta, find being a "civvy woman" in Iraq surrounded by soldiers?

She answers with a laugh. "It can lead to some embarrassing situations – I mean, where do you have a pee in a camp full of men? But I think people often open up to you more readily. I represent no threat and I'm probably one of the only civilian women they've seen during their whole tour so often they open up and as a portrait painter, that's so humbling.

"As you can imagine there's a degree of confusion about why I'm there so I get, 'What the f*** are you doing here, ma'am?' and I say, 'Sit down and I'll show you.' And they do and I do a 10-15 minute sketch of them."

The results scatter her studio where we sit, moving charcoal memories of young soldiers, some now no longer still alive, others with injuries that have changed their lives forever. Knowing they were done on the battlefields in moments captured away from the fighting adds to their poignancy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That tour, however, was not enough for Arabella. After Iraq she went to Afghanistan, returning several times over five years and even taking her husband, a business entrepreneur Dominic Elliot, with her to explore the land more.

"When I was in Helmand Province, I was told it wasn't the real soul of Afghanistan and to understand the country, you must go to the east, to the north, but not here," she says. "Many journalists at the time were quite rightly focusing on the military because our people were out there fighting the campaigns. What they weren't at liberty to reveal or bring out was the essence of the Afghan people, the soul and the majesty of an incredibly proud people, so I tried to balance that coverage in my work.

"I met some incredible women," she continues. "I was flown down to Lashkar Gah and spent a day with the first Afghan women's police team. We talked and we exchanged stories of work, children and all that women talk about."

Sadly, one of the women, Lieutenant Islam Bibi, the most senior female police officer in Helmand Province, was gunned down and killed on her way to work four months later.

The memory of that encounter still resonates with Arabella as she explains why she tries and capture man's inhumanity to man. "Islam Bibi has become in my mind an example of how you can't live without hope," she says. "She was such a powerful symbol of that hope and she knew the risks were so great, but she knew there would be other women who would follow in her footsteps."There is so much that can be got out of the horror of war and I think that's what I'm compelled to try and reveal – dare I say the beauty that can often lie behind the tragic?"

That idea certainly lay behind the piece which put Arabella in the spotlight in December 2015: Flight, her installation highlighting the refugee crisis that was then starting to grow.

"I was in Lesbos and I was overwhelmed by the number of refugees - not just from Syria, but Iraqis and Afghans, too. Having seen what was going on in Afghanistan, one couldn't help but feel a degree of culpability. Ask them why they were leaving the country and they said how it was just too dangerous to stay with Isis. One feels responsible in the general way."

She felt she had to do something but for once, this lifelong painter – she won her first art prize at the age of eight and studied in London and Florence – didn't pick up her sketchbook. "For the first time in my life I felt painting was not the right medium to respond to this crisis. Painting is slow; it needs time. This crisis needed something much quicker and more visceral."

Her response came, appropriately enough, in the shape of a boat – a real dinghy, originally made for 15 but which had carried 62 people across the sea before failing and leaving the refugees to be rescued. She hung it high in St James's Church in Piccadilly, suspending three lifejackets from it, one of them a child's. "I pulled out so many children and babies from the sea in Lesbos – alive, I must say, but as a mother of a four and a six-year-old, it was almost too much to bear," she says.

As a committed Christian, the work had an extra significance. "A boat is almost a refuge in itself, like a church, and I thought how powerful it would be to have this boat hanging in this church over Christmas with three lifejackets hanging down from it, symbolising the holy family and their flight out of Egypt."

Such a subject can seem a world away from painting portraits for some of Britain's top society figures. Arabella's clients include high court judges, military leaders, business executives, members of royalty – Prince Michael will sit for a second portrait later this year. She, however, sees no difference between this and her touching paintings of children playing in the dust in Afghanistan.

"You're dealing with the human condition and you're trying to paint what it means to be a human. Whether you're a woman today – like Clarissa Farr, the headmistress of St Paul's Girl's School, who I'm painting for her retirement, with all her responsibilities – or a soldier fighting in Iraq, or a refugee fleeing the bombs and persecution, you're a human being and that's where my work comes together."

Portraiture, she says, is "a three-way process: it's a triangle between the painting, the artwork, the sitter and the artist". Mirrors around her studio let the sitter see themselves and even watch Arabella in action, working on their painting.

Clients also have a say in every aspect of the portrait, from the clothes they wear to the way they sit, even the style of the painting, if it is relaxed or formal, if they are sitting or standing. "It's a partnership and I ask their input the whole way along," Arabella says. "They become part of the process, part of the work. I'm not objectifying them and saying, 'It's me and you'; it's us together and the artwork develops in a whole different way as a result.

"It's so important to have live sittings to try and get – almost as Virginia Woolf writes - to try and get the changing light across the landscape of someone's character. So they can be telling a sad story about some aspect of their life and you'll try and get something of that in, then they'll tell me something hilarious or outrageous or raise an eyebrow and bang! You want to get that in as well. You're trying to get the shifting dynamic. That's what's so exciting about portraiture: you're trying to get the character.

"I use what I call 'significant selection' - selecting what in essence defines that person. And that's not in looks; it is written in their face or in a gesture of their hands. And of course, to quote Leonardo da Vinci, the eyes are the windows of the soul. Most of my portraits are with the sitter looking straight at you, following you around the room. I want them to lock you in."

It is an intimate process. Portraits generally take between three to five sittings, each one lasting for two to three hours. You can see how much Arabella enjoys the process. "It's a wonderful thing to get to know another human being in the intimate surroundings of this studio," she says. "We listen to music and we share. It's such a privilege. I love it."

It is a good job she does - Arabella has 28 commissions to fulfil this year and is planning a new exhibition, Hidden, to be shown next year to raise awareness of the work of the Royal Hospital Chelsea helping army veterans. She also hopes to return to Iraq in the near future and will work with St John's Eye hospital in Jerusalem, which she says will be an "exploration of Jerusalem" itself. "I just love human beings and painting them," she says.

Throughout our interview, Arabella emphasises her points with gestures to her portraits and sketches, bringing up grand-scale works on her computer when necessary. Each piece seems engraved in her memory and I wonder if she can remember her first portrait. She laughs.

"It was of a pony," she says. "My father still has it in his study. I was so proud."

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more