Patek Philippe and the art of grand complications

Master watchmakers and artisans work on a micro scale to produce masterpieces

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ultra-luxe watch brand Patek Philippe is renowned for creating some of the most sublime timepieces the world has ever known. And the pinnacle of achievement for the watchmaker, founded on excellence almost 180 years ago, is its grand complications.

The exact definition of a grand complication is continually under review in horological circles, but, in essence, it is a skilfully engineered watch that comprises many highly complex functions. Traditionally, these additional features include the tourbillon, grande and petite sonnerie striking mechanisms, minute repeater, perpetual calendar (this takes account of monthly variations, including those in leap years), moon phases, and split-second chronograph.

However, the grand in grand complication also refers to the combination of these functions; how these puzzle pieces work together in harmony within the architecture of the timepiece, which over the decades has become smaller and thinner. Patek Philippe's most complicated wristwatch to date – the Grandmaster Chime Ref 6300G, a white gold edition released last year – houses 20 complications and comprises a staggering 1,366 parts. It is a less ornate version of the hand-engraved 18k rose-gold Grandmaster Chime 5175, which was unveiled in 2014 for the house's 175th anniversary, and of which only seven were made; one is kept for posterity – a cool $2.6 million (£2 million) addition to the family at the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Compared with the brand's classic Calatrava watch, first launched in 1932, the 6300G is something of a beast. The movement of the Calatrava generally ranges from 2.53 to 3.3mm in thickness, depending on the model; this is slimmer than a grain of rice. The caliber of the 6300G, meanwhile, measures 10.7mm (since we're talking carbs, this is just slightly thinner than a slice of bread). But although it's considerably larger, the functionality of the latter chiming movement beggars belief – little wonder it takes a staggering four months to assemble.

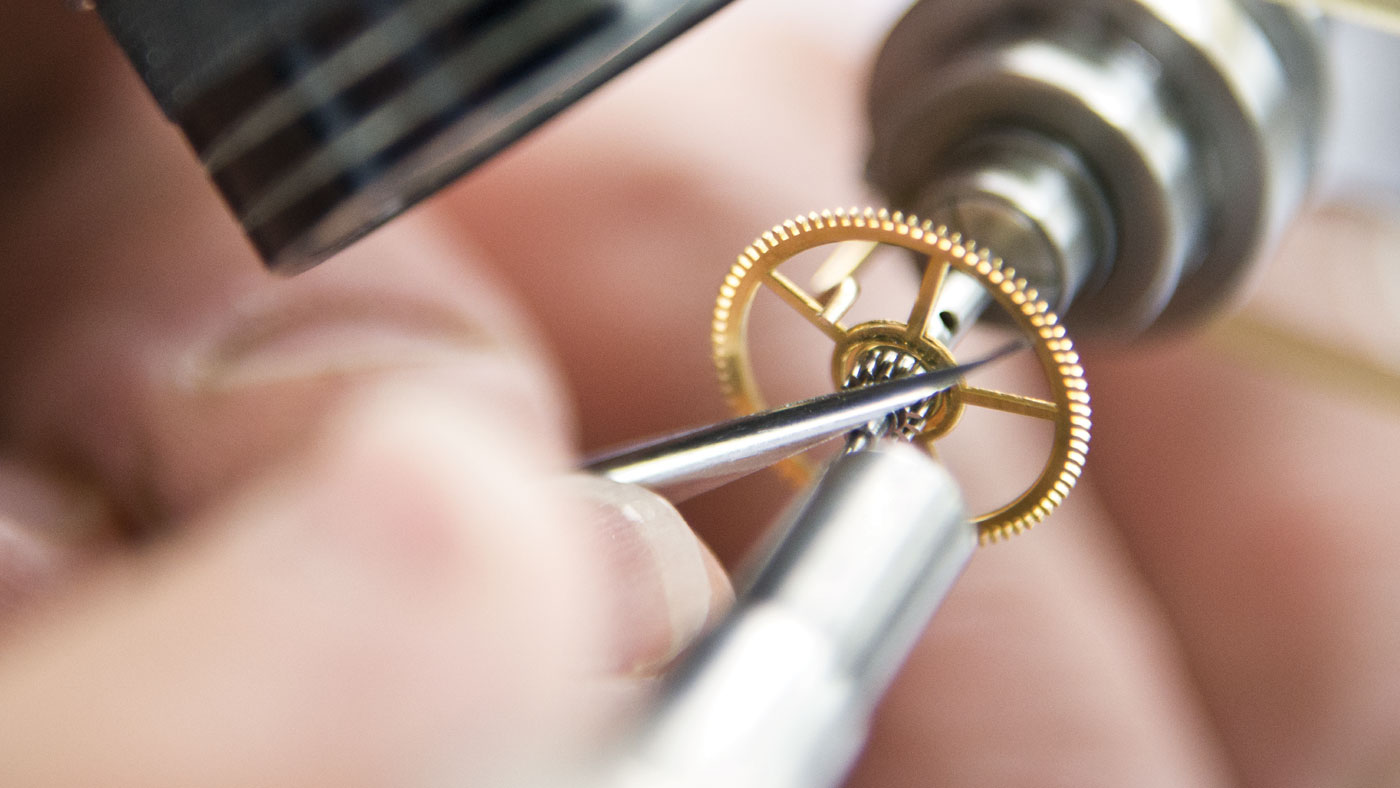

As with all Patek Philippe grand complications, hundreds of hours will have been poured into sculpting every micrometre of its make-up prior to assembly: for example, each wheel must go through 40 to 60 operations before it is fit for purpose. Furthermore, each wheel’s teeth, as well as those on its matching pinion (tiny cogwheel), is polished by hand on a wooden grinding wheel to reduce friction and ensure the smooth running of the movement. On average, there are 60 wheels in every Patek Philippe grand complication minute repeater, and more than 200 in the Grandmaster Chime. With imperceptible operations such as these, Patek Philippe leads by example in the world of superlative luxury.

Like all masterpieces created on a miniature scale – from the tiny Tudor portraits painted by Nicholas Hilliard to the contemporary micro-sculptures of Willard Wigan, which sit within the eye of a needle – Patek Philippe’s virtuosity requires years, if not decades, of honing. At the Swiss watchmaker, the micromechanical sophistication of grand complications is artistry seen through a wide-angle lens: it takes hundreds of people to create such a timepiece (about 400 in the case of the Grandmaster Chime 5175), working from the concept stage right through to assembly in the company’s workshops – and that’s before you consider the coterie of highly skilled workers specialising in the art of marquetry, gem-setting, engraving, guilloché and enamel work that is applied to the dials, casing and bracelets. The 5175 watch is an extreme example, but in terms of complexity, the gradient between different grand complications is relatively gentle; they are all spectacularly intricate, as proven by the house’s earliest timepieces.

Auction-room icons such as the Stephen S Palmer Patek Philippe Grand Complication No. 97912 – a pocket watch manufactured in 1898, comprising a grande and petite sonnerie, minute repeating perpetual calendar, split-second chronograph and moon phases – made headline news when it was sold for $2.25 million (£1.73 million) at Christie’s in New York in 2013. More significantly, there is the Henry Graves Supercomplication pocket watch, which raised a record $24 million (£18.4 million) at auction in 2014. The most complicated watch in the world to be made without the use of computer technology, it boasts 24 complications, more than 900 parts, and took seven years to make; it was completed in 1932.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These are just two of the storied Patek Philippe grand complications to have made history: given the brand’s lineage, there is, unsurprisingly, a dizzying panoply, and the ‘manufacture’ is responsible for a record number of world firsts. To skim the surface, these include the split-second chronograph, the annual calendar mechanism and the world time mechanism, as well as a catalogue of pioneering ultra-light / anti-magnetic silicon-based components that have raised the bar for the luxury watch industry as a whole, establishing Patek Philippe as a leader in the development of micro and nano-technologies. For example, innovations such the Spiromax balance spring – part of a trio of patented components collectively known as Oscillomax, the brand’s answer to a micro energy saver – have meant giant leaps in accuracy, reliability and efficiency. This holy trinity of the Swiss watchmaking world has resulted in longer power reserves for self-winding watches and thinner movements within the Patek Philippe portfolio.

Indeed, the watchmaker holds more than 120 patents for its inventions, and the fabrication of its grand complications, from caliber to case, is done entirely in-house. Let’s not forget, too, that Patek Philippe gave us the crown with the first timepieces that did not require a key; one of these was snapped up by Queen Victoria.

It was women who started the trend for wristwatches, since until the early 20th century it was considered louche for a man to wear a 'bracelet' watch, unless he was in the military. Patek Philippe created the first Swiss wristwatch for the Countess Koscowicz of Hungary in 1868; a swirly yellow-gold piece, set with diamonds, it looks like an ornate miniature mantle clock for the wrist. The brand’s first striking wristwatch was a ladies’ five-minute repeater housed in a platinum case, released in 1916. While it’s clear that the majority of horological enthusiasts are men – a strong association with maritime, airborne and automotive pursuits has played no small part in this – Patek Philippe has, in the last five years in particular, expanded into grand complications for women. This shows there is a growing female interest in the mechanics of highly complex movements, where once the focus was solely on the beauty of the dial and precious jewellery settings.

Last year, Patek Philippe unveiled its first haute joaillerie minute repeater for ladies, encrusted with more than 6.25ct of precious stones. There are five versions of the watch: one for each season, set with different coloured gems – red rubies for autumn; blue sapphires for winter; green emeralds for spring; yellow sapphires for summer – and a fifth style, the Four Seasons Symphony, with a diamond dial and bezel peppered with rainbow sapphires.

You may wonder why it has taken 178 years for Patek Philippe to develop these bejewelled, made-to-order minute repeaters given the company’s reputation for horological wizardry through the decades. A case in point is the new, retro-styled 5320G Perpetual Calendar, which has literally been 'crafted for eternity'; a watch so precise (it recognises months with 28, 29, and 31 days, and leap years) that it won’t require a manual date change until 2100, a secular year according to the Gregorian calendar. The answer lies with the pursuit of melodic perfection, which can take years of research when it comes to the delicate art of designing minute repeaters. In the case of the Symphony collection, the use of such a generous amount of gemstones adds weight to the timepiece, which can significantly affect the tonality and timbre of the delicate chime mechanism. And at Patek Philippe, they take their chiming timepieces very seriously.

The apogee of technical finesse, sometimes referred to as ‘the queen of grand complications’, a minute repeater tells the time like the most perfect musical box, striking the hours, quarters and minutes at the push of a button; only in this case, the movement that enables it to chime so beautifully is sometimes just 5.05mm thick. Hundreds of parts – 342, to be precise, for the Symphony collection – interact harmoniously in a feat of engineering that looks like it could only have been assembled by a robot. And yet it's not.

During its manufacture, a Patek Philippe minute repeater is assembled and adjusted by a single master watchmaker, but before the components reach him, they must pass through the hands of specialised artisans who turn every single piece of metal into a mini work of art. This is no overstatement. CNC (computer- controlled) machinery and industrial presses fabricate the raw forms of plates, bridges, levers and springs with steady precision, but this is just a baby step in the journey towards making such a sophisticated timepiece.

Once the shapes are cut, they undergo various finishing operations by hand, which include smoothing down, chamfering, polishing and trimming, as well as minuscule decorations like perlage (a pattern comprising small circles) and the house’s famous wave-like Côtes de Genève (Geneva Stripes). The specialists follow diagrams that are blown up to giant proportions. One artisan I am introduced to is looking at a line drawing of a striped kidney shape. "I am adding the Cotes de Geneve to this component," she says, guiding her tweezers to a tiny silver dot, no larger than an ant, on her worktop. Another lady is bevelling (anglage in French) the skeleton baseplate of a grand complication; she has a 'before' and 'after' version to show me.

"There are 30 hours between the two," she explains, matter-of-factly. "I have to leave space for the engraving; if I remove so much as a fraction of a millimetre more than I am supposed to... well, it is no good!" she laughs. It takes the patience of a saint, as well as a strong resolve, to undertake such work, especially given the fact that a finished component may not pass the house’s stringent controls, which culminate in the Patek Philippe Seal, the ultimate stamp of approval. Depending on their complexity, finished movements are typically assessed over a period of 30 days; even when a watch is complete after casing, it is tested for a further 20 days before it is vacuum packed and prepared for the official handover to the client.

"Sometimes it is that the colour is not uniform, or it could be an uneven surface," says the expert artisan of the quality control that her labour- intensive baseplate work is put through. "The play of light also has to be beautiful. There are many reasons why it can’t go to through. It has to perfect, because otherwise the next person is not able to continue their work."

Elite Swiss watchmaking is often perceived as a clinical and sedate world, inhabited by men in white coats who work in hushed tones. Office banter is admittedly not conducive to such specialised work, but the atmosphere at Patek Philippe’s albeit pristine ‘pre-montage’ workshops debunks this myth.

"We are the superwomen!" exclaims the head of this all-women atelier, which is responsible for fixing micro components onto the completed '30-hour' baseplate. In this convivial atmosphere, the women work from another diagram that has more colour coding than the London Tube map; a network of rainbow lines point to where each tiny spring, ruby and pin must be placed, ready for the watchmaker. This is a truly complex vocation that requires scrupulous attention.

"The baseplate arrives naked, so we prepare her for her final dress. Everything is sur-mesure, like haute couture!" laughs the supervisor, who is holding a box full of what could indeed be described as sparkly nano-sequins – perfectly formed specks of ruby.

The watchmakers of the grand complications are situated on the third floor. In the haloed atelier that assembles the iconic Grandmaster Chime caliber – all 1,366 components of it – the watchmaker works from a special kit comprising five boxes of 36 compartments, each containing all the components that have been painstakingly prepared in the workshops below. I can’t resist asking him if he’s ever lost a part. "Oh yes, it happens every day!" he laughs, although I suspect he’s only teasing. As with the building of the Large Hadron Collider, you wouldn’t want to miss a bit.

Creating the perfect chime requires methodical fine tuning, since even the slightest internal vibration can cause the sound to distort. Every element added to the watch, including the case, can affect its musical tone. The word 'assembly' therefore doesn’t really do this stage justice; the watchmaker of a chiming timepiece is at once a mechanic and sound engineer who must work with the precision of a keyhole surgeon.

"When we have completed the work, we pass it before Monsieur Stern [Thierry Stern, president of the family-owned company], who listens to the chime that has already been through many acoustic tests," explains the specialist Swiss watchmaker. "And sometimes, of course, he refuses it, so we say, 'Pas de problème’, and we perfect it, even if this takes another two months. The sound is something that is incredibly delicate and involves so many variables. But when it is all good, we go out and celebrate. We have a few drinks!"

What a tremendous buzz that first celebratory sip must bring. And the incredible sense of accomplishment is forever inscribed in the history of watchmaking, preserved in a Patek Philippe grand complication; not just an instrument of ingenuity, but a time capsule of master craftsmanship for generations to come.

Alexandra Zagalsky is a London-based journalist specialising in luxury, art and travel. She began her career working on a cultural guide for English-speaking expats in Paris, where her first major break was an interview with Lionel Poilâne, the late baker of Saint-Germain-des-Prés famed for his signature sourdough loaves. Returning to London in her early 20s, she went on to write for not only The Week but also The Art Newspaper’s Art of Luxury supplement, The Telegraph and The Times, as well as art and design platforms including 1stDibs’ Introspective Magazine and the magazines of the V&A, Sotheby’s and Christie’s. She studied fine art and art history at Goldsmiths, University of London and continues to explore travel journalism through the lens of art, craftsmanship and culture.