Should police work with anti-paedophile vigilantes?

Role of unauthorised volunteers in convictions is growing, but serious concerns remain

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

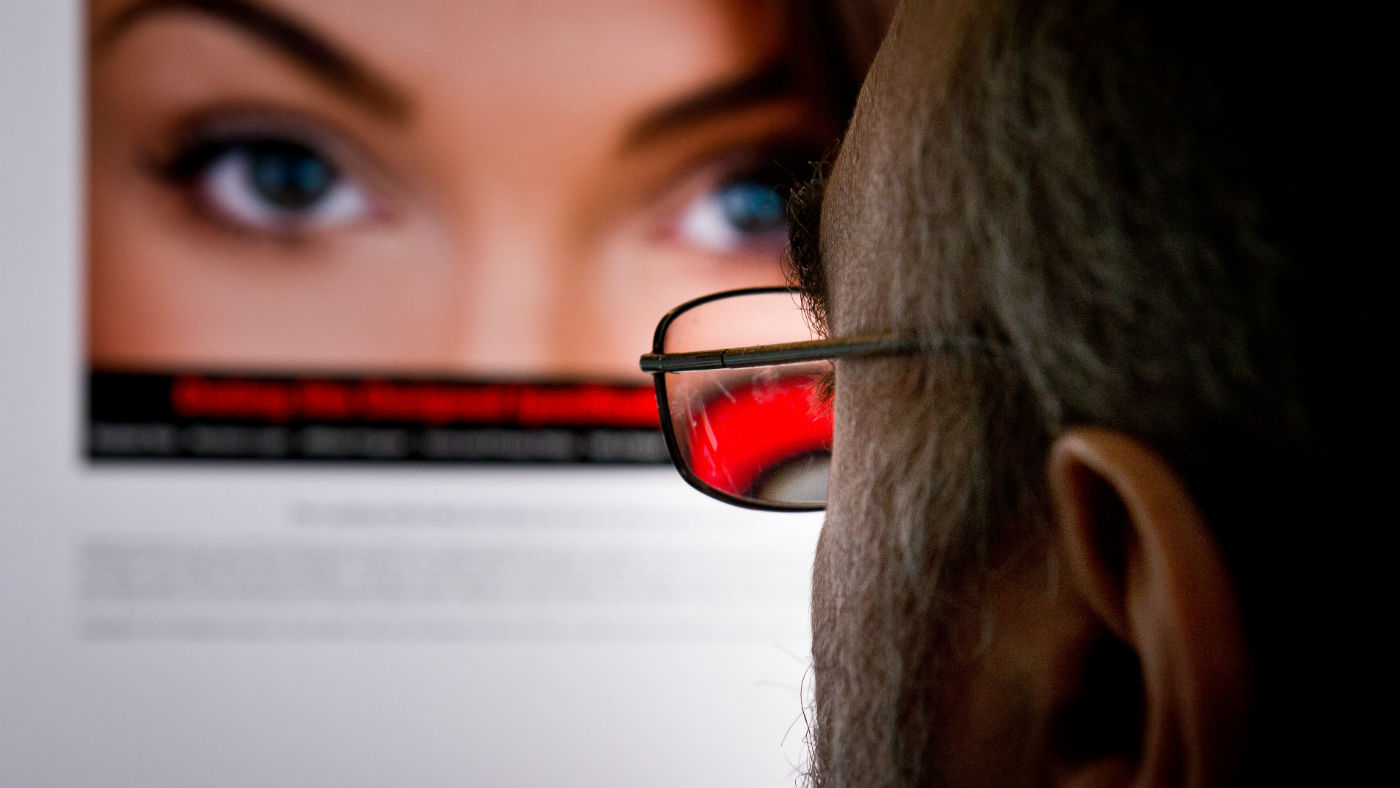

The UK’s chief police officer for child protection has said that police may be forced to work with vigilante anti-paedophile groups to avoid them unintentionally sabotaging criminal investigations.

Chief constable Simon Bailey says that vigilante organisations are “not the answer”, despite figures obtained by the BBC showing that an increasing number of child sex offence cases are using evidence gathered by volunteer “paedophile hunters”.

Under names like Dark Justice and Guardians of the North, these vigilante organisations create fake underage online personas to lure suspected paedophiles out of hiding.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The groups save any evidence of sexual grooming, such as chat logs, pictures and videos, to be passed on to the police.

If the unsuspecting groomer arranges to meet with their “victim” in real life, they are confronted instead by members of the organisation. Videos of such encounters have been viewed millions of times online.

“I'm not going to condone these groups and I would encourage them all to stop,” Bailey told the BBC, but I recognise that I am not winning that conversation.”

The role of vigilante groups in convicting paedophiles has expanded rapidly in recent years. In 2016, 44% of cases involving adults convicted of trying to meet a child after sexual grooming relied at least partially on evidence obtained by volunteer anti-paedophile groups, compared to 11% in 2014.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, Bailey, and many others in professional child protection, are concerned that volunteer “paedo hunters” end up doing more harm than good.

“They don’t take into consideration the safeguarding risks to children, the implications of a failed operation or the compromise of one of our own operations,” he told BBC Radio 4.

A mistake on the part of an amateur paedophile hunter could be costly - a child sex offender who realises they are the subject of a sting might destroy crucial evidence or retreat deeper underground to continue their offences even further from the eyes of the law.

There are also serious public safety implications when it comes to exposing alleged paedophiles in public. One group calling itself The Hunted One came to prominence earlier this year for a botched confrontation at the Bluewater shopping centre in Kent, which ended with two witnesses attacking a man lured under the belief he was meeting a teenage girl.

The police’s public protection unit said at the time that the incident highlighted “significant concerns” about vigilante justice.

Although most self-styled paedophile hunters are adamant that they follow the law in their confrontations, there is a risk that one of the millions of people who watch such videos online could post identifying information that could endanger a suspect or their families.

Uploading or live-streaming alleged encounters with paedophiles before or during a trial could also prejudice criminal proceedings.

With these issues in mind, Bailey says that finding a way for volunteer groups to operate in tandem with official investigations was a matter of “real complexity”.

-

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Georgia police post warnings outside sex offenders’ homes ahead of Halloween

Georgia police post warnings outside sex offenders’ homes ahead of HalloweenSpeed Read Signs warn trick or treaters to avoid knocking on doors of houses belonging to sex criminals

-

Rotherham gang ‘drugged and raped schoolgirl in Sherwood Forest’

Rotherham gang ‘drugged and raped schoolgirl in Sherwood Forest’In Depth Victim was later forced to have abortion, court hears

-

UK child abuse: the shocking statistics revealed

UK child abuse: the shocking statistics revealedIn Depth Home Secretary Sajid Javid threatens to impose penalties over tech firms’ failure to remove ‘horrific’ images

-

Winston Churchill ‘probably’ sexually abused as boy

Winston Churchill ‘probably’ sexually abused as boySpeed Read Biographer Lord Dobbs says former PM suffered ‘appalling treatment’ at school

-

Thousands seek help to stop viewing child abuse images

Thousands seek help to stop viewing child abuse imagesSpeed Read More than 36,000 people contacted Stop it Now! child protection charity in UK last year, a rise of 40%

-

Jehovah’s Witnesses could face child sex abuse inquiry

Jehovah’s Witnesses could face child sex abuse inquirySpeed Read Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse says there have been ‘a considerable number’ of complaints against the group

-

Three Girls: Petition calls for award for Rochdale whistleblower Sara Rowbotham

Three Girls: Petition calls for award for Rochdale whistleblower Sara RowbothamSpeed Read More than 130,000 demand social worker, played by Maxine Peake in BBC1's Three Girls, be acknowledged

-

Harvey Proctor accuses police of 'homosexual witch hunt'

Harvey Proctor accuses police of 'homosexual witch hunt'Speed Read 'I'm a homosexual. I'm not a murderer or a paedophile,' former Tory MP tells reporters