Why mass extinctions matter

Human activity is causing the most rapid species loss for millions of years, but there is still time to act

Evidence suggests that Earth is at the beginning of its sixth mass extinction event, the most rapid loss of species since dinosaurs were wiped out 65 million years ago.

The disappearance of thousands of plant and animal species, caused almost entirely by human activity, will have serious ecological, economic and social consequences, experts have warned.

“It’s folly to think we can drive almost half of everything else to extinction, but we will be just fine,” National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore says in his forthcoming three part Nat Geo WILD documentary series, Photo Ark, which starts on Nat Geo WILD at 8pm on 23 October.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The programme takes viewers behind the scenes on Sartore’s 25-year mission to photograph some of the rarest animals in the world, during which he has amassed studio portraits of more than 6,000 species. Many of these no longer exist today.

There is some good news, though, as scientists say there is still time to slow the process down, but only if rapid and radical action is taken.

That’s where Sartore believes he can make a difference. “I’ve seen how photos can lead to change,” he says in the first episode of the series. “Pictures I’ve made of parrots in South America and koalas in Australia help pressure local governments to protect those animals.”

By looking these animals in the eye, we begin to care about them and understand their importance to the health of our planet.

What’s happening and why?

Mass extinctions are not new. There have been five large-scale species die-offs in the past 450 million years, says National Geographic, all caused by catastrophic natural events such as asteroid strikes and volcanic eruptions.

The current extinction, however, is the first man-made event. Population growth, climate change, habitat destruction, pollution, excessive hunting and wildlife trafficking are all damaging marine and terrestrial ecosystems so quickly that animals do not have time to naturally adapt or recover.

Although extinction is a natural process, landmark research published in 2014 found that human activity is probably causing some species to disappear up to 1,000 times faster than normal.

A third of all land vertebrates, including reptiles, birds and amphibians, are experiencing a decline in their populations, according to a major study on extinction published earlier this year.

In the past, “you would find that one species might go extinct every 5,000 years,” said Dr Nisha Owen, from the Edge of Existence programme at the Zoological Society of London.

But since the 1500s, we’ve lost more than 70 species of mammals and at least 140 bird species, she said during The Week’s debate on mass extinction made in partnership with Nat Geo WILD. “And those are only the species we know about.”

Which species are most under threat?

A study released earlier this month found that the biggest and smallest animals are most at risk of extinction, with medium-sized species most likely to survive, the BBC’s Helen Briggs reports.

Amphibians are the most likely to be at risk out of any animal group because of their sensitivity to environmental shifts, according to the US Center for Biological Diversity. As such, they “should be viewed as the canary in the global coal mine, signalling subtle yet radical ecosystem changes that could ultimately claim many other species, including humans,” it warns.

But it’s not just animals we should be worried about, as plant species are also under severe threat.

While elephants and rhinos “thoroughly deserve our support,” says Ann Tutwiler, director general of Bioversity International, in The Guardian, “if there is one thing we cannot allow to become extinct, it is the species that provide the food that sustains each and every one of the seven billion people on our planet”.

Why should we care?

Humans are greeting mass extinction with little more than a “yawn and shrug”, says National Geographic journalist Simon Worrall. “One fewer bat species? I’ve got my mortgage to pay. Another frog extinct? There are plenty more.” But extinction has profound effects on the fragile ecosystems on which human life depends, says Dr Owen. These systems “provide us with clean air, clean water [and] the food that we eat”, she says.

The loss of even a single plant or animal species can affect humans in a host of ways, from food shortages and price rises to the loss of tourism revenue and potentially life-saving drugs.

Then there are the problems we don’t know about. Such a dramatic drop in biodiversity can have unforeseen consequences for the planet, warns British filmmaker and explorer Benedict Allen.

“You have one tree in Borneo with a thousand species of insects. What do those insects do for us? We don’t know,” he said during the Nat Geo WILD debate. “That’s the most terrifying thing to me.”

Sartore was forced to confront similar questions while filming for Photo Ark in Madagascar, where deforestation is a serious problem. “The forests get cut because people need to eat,” he says, but once they’ve cut down trees to plant crops or make charcoal, “the rains come and it washes everything away, totally erodes the surface of the earth.”

The resulting habitat loss has a dramatic effect on forest-dwelling species and the ecosystem they support. “You can’t cut all these trees down and have a stable environment,” Sartore says. “The world’s ending a little bit at a time.”

What can be done?

Conservationists argue that solutions exist, but time is fast running out to implement them.

“Previous mass extinctions might have been inevitable but it is not too late to stop this latest assault on our ecology,” said a recent editorial in the Lancet Planetary Health.

However, “unprecedented cooperation is needed between policymakers, international organisations, research scientists and civil society to preserve and maintain our biodiversity – and to protect the world from ourselves,” it adds.

Experts agree that top priorities include ending fossil fuel dependency and adhering to the Paris climate agreement to mitigate further global warming, as well as reducing the global consumption of meat and fish to protect against overhunting, deforestation and habitat destruction.

“We mustn’t forget that many of the threats that these species face are driven by Western consumerism,” says Dr Owen. “It’s us who need to think how we can live more sustainably.”

Photo Ark is on Monday 23 October, Tuesday 24 October and Wednesday 25 October at 8pm on Nat Geo WILD.

Photo Ark ©WGBH Educational Foundation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

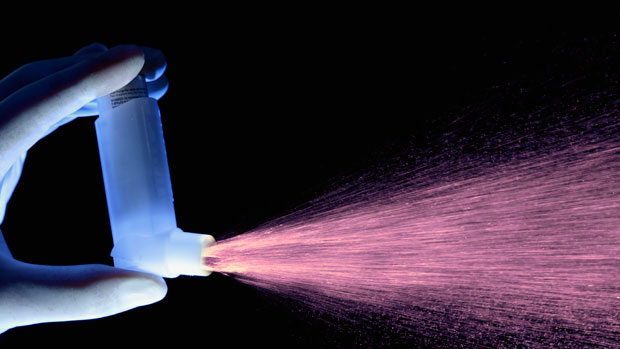

Why asthma can be bad for the environment

Why asthma can be bad for the environmentThe Week Recommends Cambridge University study finds some inhalers release greenhouse gases

-

Which island paradise would you save?

Which island paradise would you save?feature Wildlife experts nominate the unique, biodiverse places they love above all others

-

ZSL Animal Photography Prize 2014 - in pictures

ZSL Animal Photography Prize 2014 - in picturesThe Week Recommends Award-winning photos that 'take your breath away' will go on show at London Zoo