America's core misunderstanding about the Taliban

Americans don't die for religion anymore. Did we forget many people still do?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Of all the Afghanistan explainers I've read this week — every analysis of what went wrong and how we should respond and who's to blame and what it all means for American identity, policy, and security — one insight stands out as both too little acknowledged and incredibly important.

It comes from a new book, The American War in Afghanistan: A History, excerpted at Politico in early July. The author is Carter Malkasian, who advised the U.S. military commander in Afghanistan and the chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The portion that caught my eye is Malkasian's consideration of the role of religion in the Taliban's persistence and success. Here's a partial excerpt:

The Taliban had an advantage in inspiring Afghans to fight. […] They cast themselves as representatives of Islam and called for resistance to foreign occupation. Together, these two ideas formed a potent mix for ordinary Afghans, who tend to be devout Muslims but not extremists. Aligned with foreign occupiers, the government mustered no similar inspiration. It could not get its supporters, even if they outnumbered the Taliban, to go to the same lengths. […] More Afghans were willing to serve on behalf of the government than the Taliban. But more Afghans were willing to kill and be killed for the Taliban. That edge made a difference on the battlefield. [Carter Malkasian, via Politico]

This distinction, Malkasian writes, was "underappreciated by American leaders and experts, [himself] included," and the resultant ignorance helped American occupiers believe "things were possible in Afghanistan — defeat of the Taliban or enabling the Afghan government to stand on its own — that probably were not."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the near aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, religion seemed more a part of the discussion around terrorism than it is now, 20 years on. The whole program was renamed within days of its launch, dubbed "Operation Enduring Freedom" instead of "Operation Infinite Justice," because, as The New York Times reported at the time, "Islamic scholars complained that only God was capable of dispensing infinite justice, and administration officials worried that allies in the Middle East would take offense." Or you may recall the 2004 controversy occasioned when then-President George W. Bush said Christians and Muslims worship the same God and merely have "different routes of getting to the Almighty."

Those stories, like most interplays of religion with the war on terror, are about the cultural gap between Muslims and non-Muslims. Particularly in those early days, American ignorance of Islam and Afghan (or Iraqi) culture was a regular source of tension. But what Malkasian describes is something different. It's a higher-order incomprehension, a chasm in understandings of religion and its place in society, of whether faith feels optional or contingent, and whether it's worth your life — and your death.

Americans live in what the philosopher Charles Taylor famously called a "secular" society. It's not that we're all irreligious. On the contrary, by Western standards, our religiosity is still quite high (albeit on a downward trend). But religion is typically compartmentalized: It's commonly considered a matter of private life. Most of our public sphere is left with only "vestigial ritual," in Taylor's phrase. "If we go back a few centuries in our civilization, we see that God was present ... in a whole host of social practices — not just the political — and at all levels of society," he writes. "But the situation is totally different today."

Religion in secularized society seems optional in a way it didn't in centuries past. We have moved, Taylor says, "from a society where belief in God is unchallenged and, indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others, and frequently not the easiest to embrace." The most devout believers in America likely know people — maybe many people, including people they love or admire — who have lost their faith or never had it in the first place or who place their faith in an entirely different God or gods. That knowledge, once gained, can't be lost, and it gives the life of faith a feeling of contingency. Our context makes it easy to realize our faith at this very moment might well be different or even nonexistent had we been born to different parents or in a different city or year.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I don't mean to suggest no one in Afghanistan is secular in this sense. Undoubtedly many are. But those Malkasian describes responding to the Taliban's religious inspiration are not — or at least they are not nearly so far down the path to secularization as the average American. Religion occupies a categorically different place in their society and individual lives, and the distinction is not so much about which faith they embrace but how they embrace it. Americans' underappreciation of religion's role in Afghan life is no doubt partly attributable to ignorance of Islam, but our comparative secularization is the greater factor. (I'd suggest a similar misunderstanding plays out on a smaller scale within the U.S., in the gap between more secular Americans and those they'd say "cling to guns or religion" — but that's another essay for another day.)

The most concrete evidence of this distinction is that final Taliban advantage in the Malkasian excerpt above: the willingness to die for faith. In centuries past, Westerners both died and killed for religious belief. Europe spent centuries wracked by wars of religion, and some of that conflict crossed the Atlantic. Rhode Island was settled after its founder was exiled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the dead of winter in 1636 because he wouldn't stop teaching "diverse, new, and dangerous" religious ideas. That easily could have been a de facto death sentence. The 17th century was not a secular age.

Modern Americans might hope we'd stand firm in our faith in the face of persecution, but for the vast majority of us, the principle will never be tested. The the possibility of dying for our religious beliefs is remote; the prospect of killing for them further still, so much so that even in a faith which permits religious violence, it may be unthinkable.

That's the very core of this misunderstanding: What's unthinkable here is not unthinkable everywhere, and you will run into trouble if you start wars as if it is.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

The Taliban's ongoing attack on women's rights

The Taliban's ongoing attack on women's rightsIn depth The group has sparked humanitarian concerns

-

Afghanistan tops list of dangerous countries for Christians, ending North Korea's 20-year reign

Afghanistan tops list of dangerous countries for Christians, ending North Korea's 20-year reignSpeed Read

-

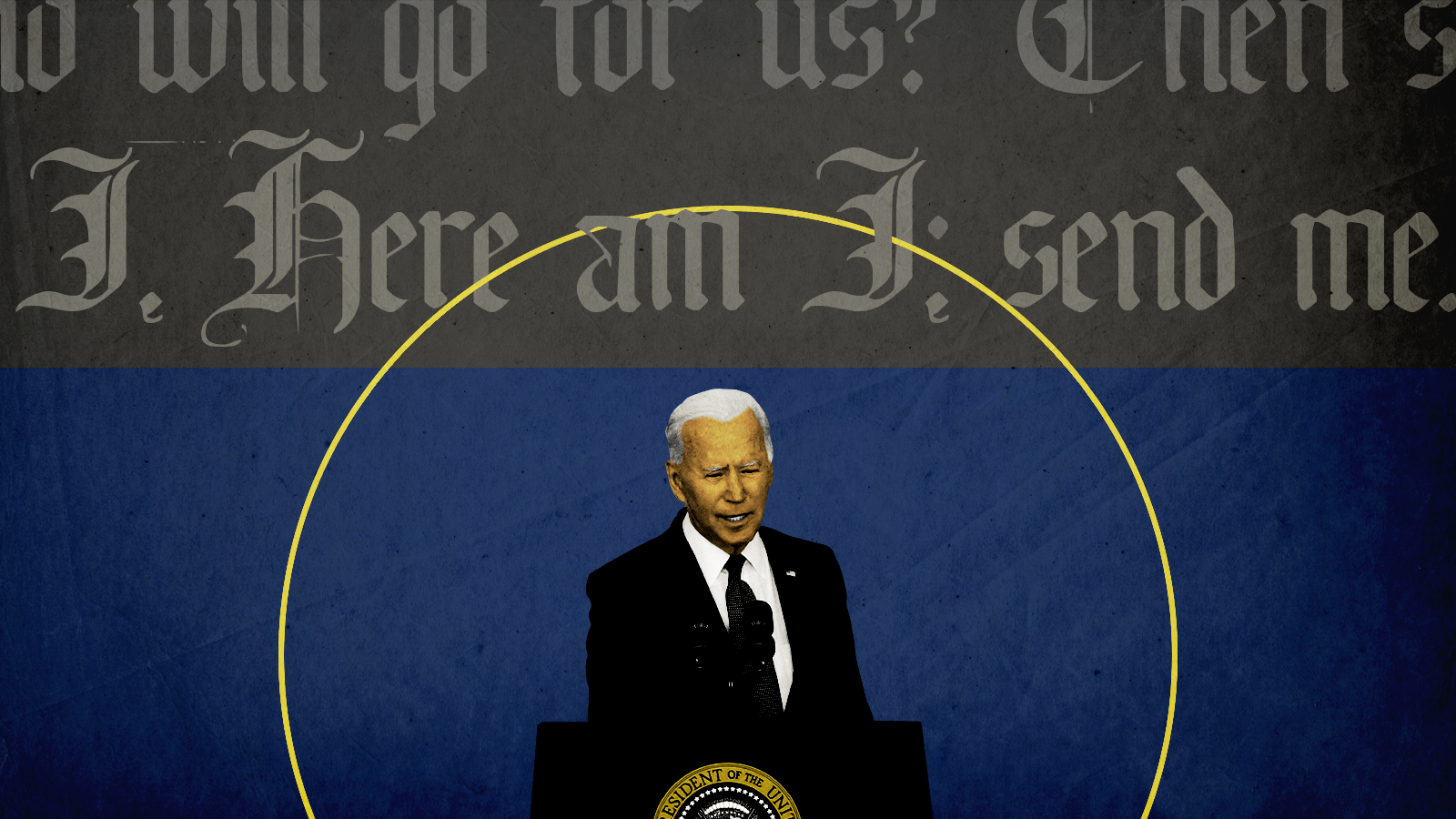

Biden chooses the wrong Bible verse

Biden chooses the wrong Bible verseTalking Point