The case for invading North Korea

The regime is an abomination. It's time to get serious about changing it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

North Korea is a joke, and shame on us for laughing. The "Hermit Kingdom" with its retro aesthetic and its goofy-looking leader makes us laugh, from our well-heated homes. That's what The Interview and "Kim Jong-Il Looking at Things" are all about.

But North Korea isn't "weird," it's not "eccentric" — it is the vilest place on the face of the Earth.

North Korea's leaders keep their entire nation in a state of perpetual semi-starvation for the sole purpose of maintaining power while they entertain themselves with prostitutes and fine foods from around the world. The North Korean regime is well known for financing itself through drug trafficking and other forms of international organized crime. Alcohol and hard drug use is positively pandemic, unsurprisingly considering life there. And forget about any sort of culture or true education or access to knowledge, or anything we consider integral to human flourishing. This is a country where everyone grows up in constant fear.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And it's really the descriptions of North Korea's concentration camps that should give anyone pause. (You owe it to yourself to read them.) If regular citizens in North Korea starve, how do you think concentration camp inmates fare? North Korea practices a system of collective punishment whereby if one person is found guilty (without trial, of course) of an offense — such as being a Christian, or participating in the black market (which everyone must do to survive) — three generations of their family are sent off to the Gulag. There are children in these camps. Many die of starvation. Those who do not have to work starting at the age of six.

It is, truly, the rape and defilement of an entire nation, a systematic and refined evil that only the human genius at its most perverted can produce. We know about it. We witness it. We see it. What are we doing about it?

We are so smug towards our forefathers. What did you do about the Holocaust? What did you do about segregation? "Oh, you don't understand, it was much more complicated than you make it out to be." We have nothing but contempt for excuses like that, don't we? Do we really want to give the same excuses to our grandchildren? And what excuses will we give ourselves?

If someone disputes that there is a moral imperative toward regime change in North Korea — I do not want to argue with him; he shows a corrupt mind. The only question remains: is it feasible? I would like to argue that it is.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

1. The military aspect

This is obviously the trickiest part. North Korea has nukes, as well as countless artillery positions trained on Seoul and South Korea. Any attempt at regime change in North Korea must destroy their offensive capabilities in one strike.

U.S. forces should be able to destroy all of North Korea's artillery in one strike. After all, if there's one thing that the U.S. military is very good at, it's launching enormous amounts of rockets and bombs with great precision. With satellite, any significant artillery positions are known. Given the U.S.'s overwhelming technological advantage and total dominance of the sky, and the effect of surprise, it should not be impossible to pull off.

The key question, then, is North Korea's nuclear weapons, and this is a question that no one without access to classified information can answer. But the North Korean regime does not possess many warheads. They cannot be stored in many locations. And it stands to reason that the U.S. intelligence community has been hard at work figuring out where they are, and figuring out a plan on how to get to them. If that could be pulled off, it's possible North Korea could fall quickly, with little harm to anyone outside the country.

(By the way, when the regime falls on its own, as it inevitably must, what will happen to its warheads, and how hard will it be to get them into good hands then?)

Those are big "if"s, but military history is full of stunning successes that were once deemed impossible, like the German push through the Ardennes, D-Day, and the Israeli Air Force's total destruction of the Egyptian Air Force in one strike in the Six Day War.

2. The geopolitical aspect

This would make everyone unhappy. South Korea is not exactly fond of the status quo, but neither is it fond of a unification that would drag down its economy.

And China would be particularly unhappy, since it views North Korea as a useful pawn. But that makes it an accomplice with the North Korean regime. And although China would be very unhappy, it would ultimately come to live with it.

First, China is not going to nuke the U.S. over North Korea. Second, we should remember that the Chinese leadership is fundamentally obsessed with keeping growth and employment up so that their people don't revolt against them. And given that serious economic or political retaliation against the U.S. would hurt that goal more than it would hurt the U.S., they will abstain from much more than gesticulation.

The U.S. should be overwhelmingly generous in logistical, humanitarian, and financial support for the North Koreans that will surely try to immigrate to China. It should even assist China in creating a buffer zone within North Korea so that it's not overwhelmed with refugees, which is China's main fear relating to a North Korean regime collapse. China might even welcome the new situation: The North Korean regime has recently gone "rogue" in its relationship with China and is today as much a headache for China as it is for everyone else. If the U.S. offers the demilitarization and neutralization of the Korean Peninsula to China in exchange for helping rebuild North Korea, China would actually come out ahead by removing U.S. troops from the Peninsula.

3. Nation-building

I opposed the war in Iraq. I thought what would happen was...exactly what happened. Iraq never was a nation, it is a bundle of fractious ethnicities and loyalties only held together by an authoritarian regime. So I get the skepticism towards nation building. But there's only one thing more stupid than thinking that with some magic pixie dust Iraq could turn into Switzerland: thinking that because nation-building failed in Iraq, it can never succeed.

In 2003, the conventional thinking was that nation-building was a cake-walk; today, it is that nation-building is impossible — dare I suggest the true answer is somewhere in between?

Here's a radical idea: East Asia and the Middle East are actually different places. North Korea has a unified country, language, culture, and ethnicity. After the regime falls, no one will fight for the Juche idea or the North Korean regime, which everyone in North Korea hates. (If you think that just because people see regime propaganda all day every day they believe it, you have a poor grasp of history and an even poorer view of human nature.)

You know what would really help nation-building in North Korea? What if there was a huge reservoir of people of the same ethnicity, language, and culture? What if those people were all already from an advanced economy with the rule of law and democracy and modern institutions and could really help the country adapt to the 21st century? What if they were all conveniently located right next to North Korea, and what if their government had a massive interest in stabilizing the region? Maybe on the southern border. We could call that place "South North Korea", or "South Korea" for short. If such a place existed, that would make facile parallels to Iraq look really dumb, wouldn't it?

Immediate unification would lead to massive chaos. Instead, the South should run the North as a kind of protectorate — people who have been living under totalitarianism for decades can't be switched over to democracy overnight, that lesson of Iraq is valid — a kind of giant Hong Kong or charter city, with civil liberties and the rule of law and all those good things. Instead of millions of famished North Korean refugees dragging down the South's economy, North Korea will find comparative advantage providing cheap labor for South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese companies as the first step on the economic development ladder. Democratization would proceed in a slow process, starting with local governance and moving on from there, within the context of a multi-decade roadmap to reunification.

—

Is this plan "realistic"? Well, if by "realistic" you mean "within the mainstream of the Washington, D.C. policy consensus" then the answer is obviously no. But that is a very narrow definition of "realistic" by any reasonable standard.

Look, I know that my plan includes a lot of wishful thinking, although I will certainly defend the idea that there is a much bigger overlap in the Venn diagram between "wishful thinking" and "things that are actually possible" than most people take for granted. But I certainly believe that the overall direction and shape of my plan is what should drive conversation in D.C. and other capitals about what to do about North Korea. North Korea's regime is an abomination, and we should be talking about how to replace it, not about how to contain it or "deal" with it.

And that is no laughing matter.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

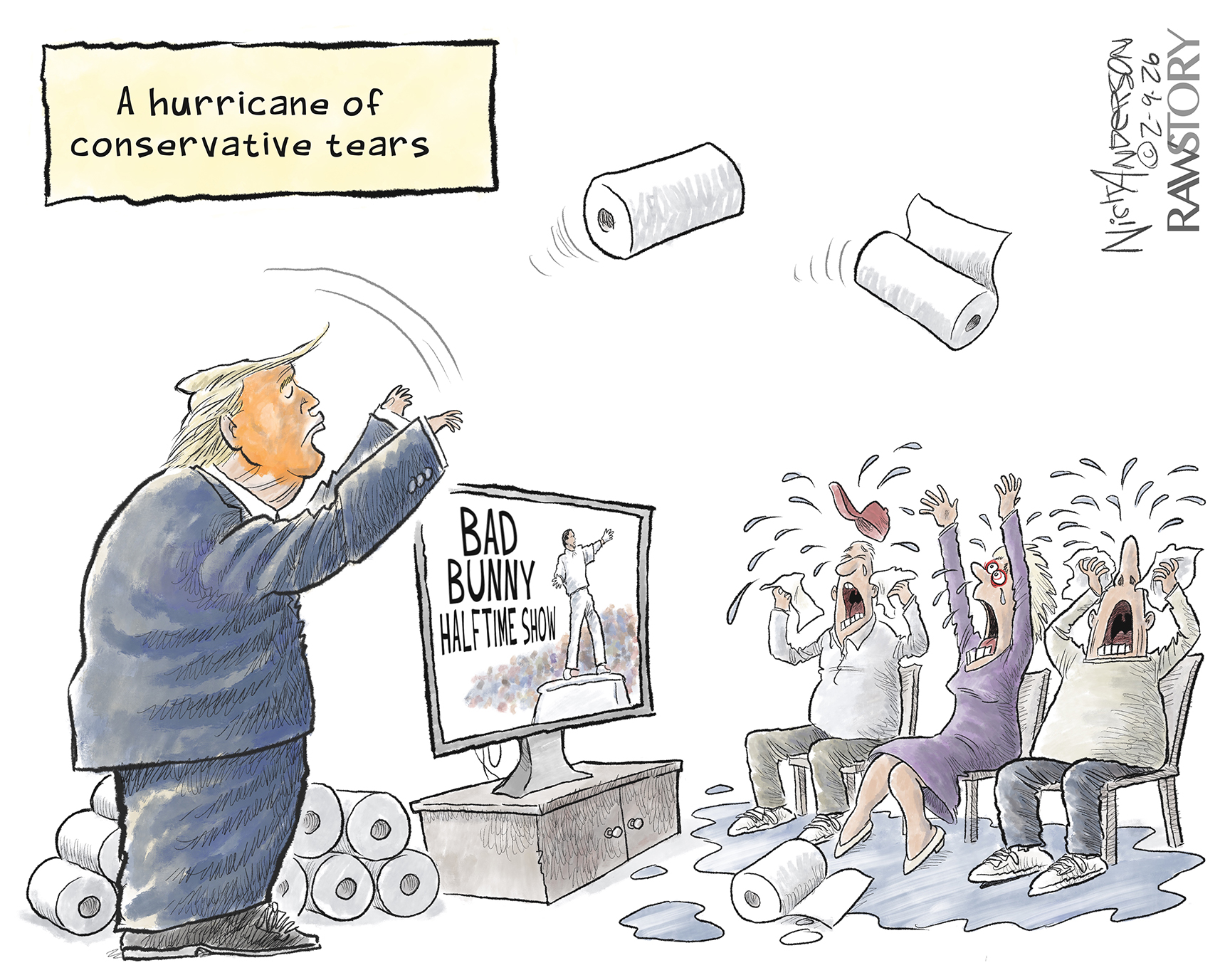

Political cartoons for February 10

Political cartoons for February 10Cartoons Tuesday's political cartoons include halftime hate, the America First Games, and Cupid's woe

-

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?Today’s Big Question Government requested royal visit to boost trade and ties with Middle East powerhouse, but critics balk at kingdom’s human rights record

-

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depth

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depthTalking Point Emerald Fennell splits the critics with her sizzling spin on Emily Brontë’s gothic tale