Why the mighty ukulele deserves a little respect

There's a reason the ukulele was once one of the most popular instruments in the world

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Anyone can play a ukulele. It has only four strings, and you can learn the three chords to accompany a song in half an hour or less. Even if you just play the open strings — my-dog-has-fleas — you're playing a pleasant major 6th chord.

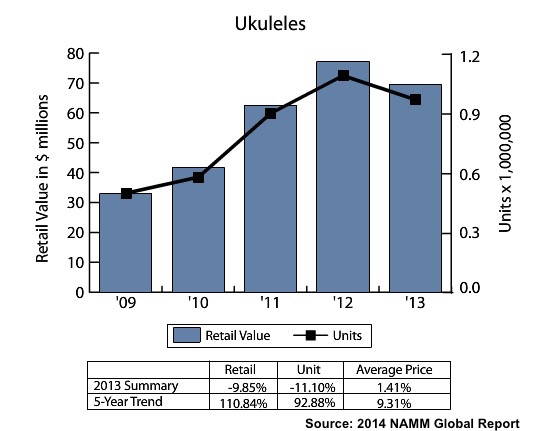

That's probably one reason why the ukulele is back in vogue. It may not be 2014's hottest Christmas gift, but most starter ukuleles cost considerably less than the Disney Frozen & Ice Palace Playset, and there's a decent chance you or somebody you know will get one this year.

Still, mainland America treats the ukulele as a toy — or at best a cute, charming, old-timey novelty instrument. "The ukulele doesn't allow for the widest range of expression, which makes it a challenging foil for Eddie Vedder," said Rolling Stone's Anthony DeCurtis in his review of Ukulele Songs.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The best distillation of the ukulele's status in today's musical hierarchy might just be this new song from Carly Jamison. "I'm getting a ukulele for Christmas, it looks just like a miniature guitar," she sings. "I don't know how to play it, from what everybody's saying, it really isn't very hard."

Perhaps ease of use, like familiarity, breeds contempt. But the ukulele isn't a toy. It also isn't a "miniature guitar" — it's a member of the lute family, developed in Hawaii by Portuguese immigrants who drew from instruments they brought over from Madeira and other places in Portugal. And this isn't the first ukulele boom on the mainland: In the 1920s, in fact, the ukulele was one of the most popular instruments on earth.

The ukulele — which means either "jumping flea" or, as Hawaii's last monarch, Queen Lili'uokalani, suggested, "the gift that came here" — was born in about 1880. Its first showing in the U.S. was at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, but the ukulele really took off on the mainland during another world's fair, the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. The ukulele's road to San Francisco had been paved by a hit 1912 Broadway play, The Bird of Paradise, that featured a Hawaiian quintet playing throughout the performance.

The ukulele was a worldwide hit, selling by the millions in the U.S. alone before World War II. Mainland luthiers like Martin, Dobro, and Gibson started making their own ukuleles to cash in on the craze. Sears Roebuck jumped aboard, too, buying leading U.S. ukulele maker Harmony in 1916; by 1923, Harmony was selling 250,000 instruments, and seven years later, 500,000 a year.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the mid-1930s, the ukulele entered a period in the wilderness, sidelined by the Great Depression and changing tastes. Amplification technology and players like Django Reinhardt allowed the guitar to break into pole position, and rock 'n' roll, the folk revival, and other forms of post-war popular music essentially buried the ukulele, at least outside of Hawaii.

There were occasional blips of popularity, thanks to novelty acts like Arthur Godfrey and Tiny Tim, military U.S. personnel returning home from service in Hawaii, and the introduction of hot-selling all-plastic Islander ukuleles developed by luthier and plastics manufacturer Mario Maccaferri — he sold about nine million Islanders between 1949 and 1969. But those popularity-boosters, especially the low-cost plastic instruments, probably helped feed the ukulele's reputation as a plaything.

The great ukulele revival arguably started in 1993, when Hawaiian musician Israel Kamakawio'ole scored a surprise hit with his ukulele-and-voice medley of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" and "What a Wonderful World." (You can hear that version, along with other ukulele selections, in a Spotify playlist below.) And then, in 2006, somebody uploaded this video of Hawaiian player Jake Shimabukuro to the new YouTube video service, and the world suddenly had to recalibrate its assessment of the humble uke:

Four years later, Shimabukuro cemented his status as a ukulele god with a masterful performance of Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" at a 2010 TED Talk. But while Shimabukuro is an exceptional musician and ukulele ambassador, he isn't the only ukulele virtuoso out there. Take James Hill, a Canadian who not only does an amazing one-ukulele version of Michael Jackson's "Billie Jean" but also uses his immense, diverse talent to train the next generation of ukulele prodigies — or whatever other instrument they pick up.

And this is the other big reason the ukulele isn't a toy: Not only can it sound beautiful in the right hands, but it also turns out to be a great tool to teach children music. Hill learned how to play ukulele in British Columbia public schools, which used a ukulele-based music education program developed in Nova Scotia in the 1970s by J. Chalmers Doane. In 2008, Hill and Doane revised Doane's seminal 1977 Teacher's Guide to Classroom Ukulele, creating the Ukulele in the Classroom program.

If you have a ukulele lying around, or are in the market for a new one, by all means learn those three chords and play "You Are My Sunshine," or learn a fourth chord and try out "Tonight You Belong to Me," just like Steve Martin (the DVD of The Jerk has a tutorial at the end). It will be fun, educational, and hopefully a joyful endeavor, and you may even find you have real ukulele chops.

Just be sure to give that little four-string beauty in your hands the respect it deserves.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein ties

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein tiesSpeed Read The younger brother of King Charles III has not yet been charged

-

Political cartoons for February 20

Political cartoons for February 20Cartoons Friday’s political cartoons include just the ice, winter games, and more

-

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?The Explainer New drug could reverse effects of sepsis, rather than trying to treat infection with antibiotics