How to grow a microscopic alien garden

You're going to need some sodium silicate

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

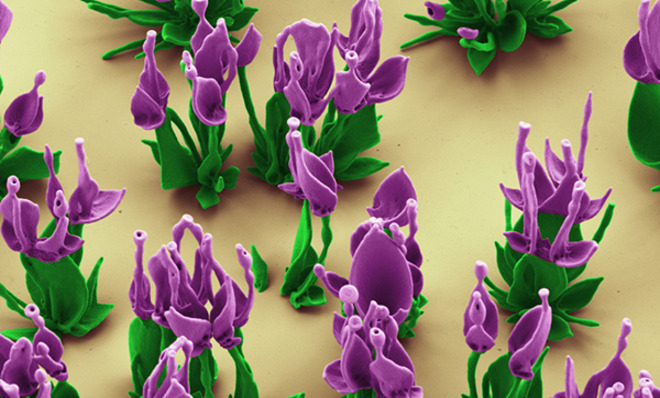

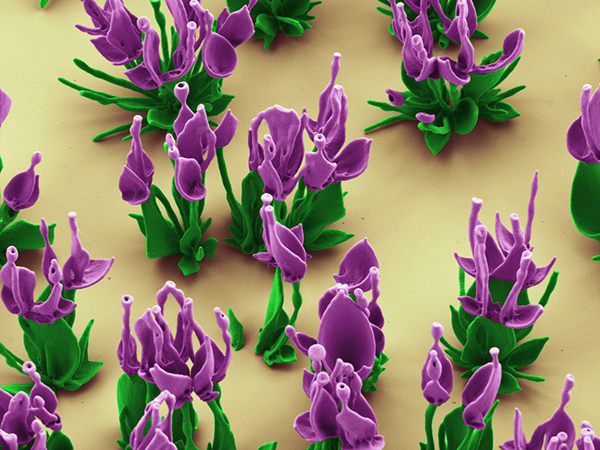

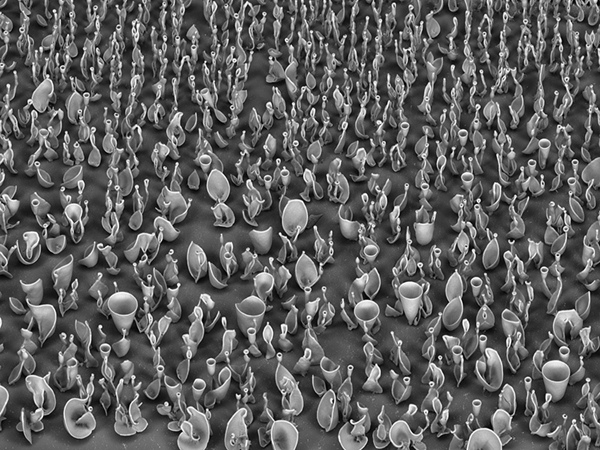

Some sculptors work in marble, others in wood… but Harvard University biomineralization researcher Wim Noorduin creates his masterpieces inside a beaker. You'd be hard-pressed to put his flowery sculptures on a regular museum pedestal, though. They're actually microscopic crystal structures many times smaller than the width of a human hair.

(More from World Science Festival: Six tiny scientific mistakes that created huge disasters)

Minerals can naturally assemble into impressive shapes, even at very tiny scales, and Noorduin's scientific research is part of an effort to understand how chemistry can drive this process. His sculptures start with a solution of the salt barium chloride and the compound sodium silicate, also known as waterglass. When these ingredients are added, carbon dioxide from the air that's dissolved in the beaker's water kicks off a reaction that forms barium carbonate crystals — and also lowers the pH of the solution near the newly formed crystals. This pH change then sparks a reaction with the sodium silicate, which deposits silica on the growing crystals.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

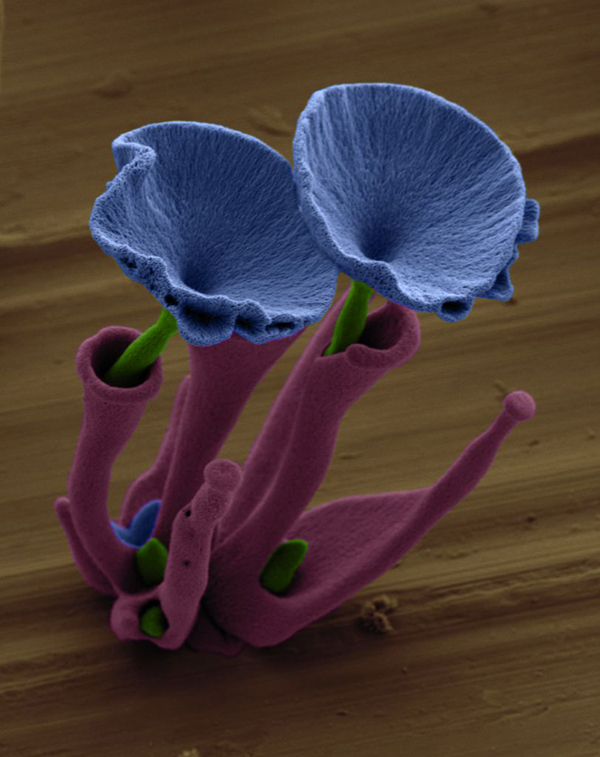

"We know how fast these structures grow and what is going to happen if we change, say, the temperature or acidity," Noorduin said in a phone interview. And knowing those principles "allows you to collaborate with the self-assembly process that's going on, and you can really manipulate the sculptures in a rational way."

(More from World Science Festival: Alan Turing vs. the mechanical Nazi)

Left to its own devices, the solution will form an intriguing forest of shapes. But human intervention can sculpt them into even more ethereal forms. There are lots of ways that Noorduin can manipulate the microenvironment inside the solution: The temperature can be altered with an ice bath, for example, or he can control the addition of carbon dioxide in the solution by capping the beaker. "If we take off the cap for just a few minutes and put it back on, in that time more CO2 will come into the solution from the air," Noorduin says. "As a result, the chemical reaction completely changes — it allows me to split structures open or make well-controlled ripples.

Noorduin can manipulate the sculptures even further, joining separate pieces into more complex shapes. He can grow a "vase" shape in one solution, then start the growth of a new "stem" shape from that and manipulate the whole into a flower. Noorduin thinks the mechanics underlying his microscopic bouquets could one day help researchers create tiny tools and devices, or manipulate everyday materials to make them stronger.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(More from World Science Festival: 11 small wonders captured on camera)

"I'm amazed by how very simple processes can give rise to complex shapes and structures," Noorduin says. While the driving force behind his work is scientific inquiry, he isn't immune to the eerily beautiful aesthetics of his work. "I am interested in trying to make the most beautiful landscapes. I got addicted to wandering around in this world."