How public transportation can adapt to suburban sprawl

The city-suburb divide has grown less stark in Atlanta, which means it will need a less centralized mass transit system

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Atlanta is a notoriously car-dependent city.

So it's no surprise that the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA), which began running 42 years ago, has always been a bit of an underdog.

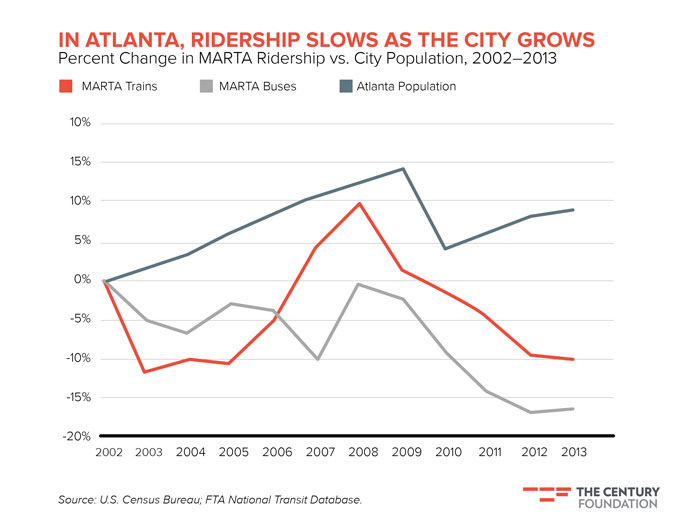

Serving only two of Metro Atlanta's five central counties, MARTA is the only major transit system in the country that receives no state-government funding. It has been hemorrhaging riders over the last decade.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But thanks to the result of an Election Day referendum, MARTA may soon find new life in the least likely of places: a suburban county that once tried to vote the agency out of existence. And with that, MARTA has the potential to serve as a model for how public transportation can adapt to increasing suburban sprawl.

Making up for lost time

In Clayton County, which is just south of Atlanta and home to the city's enormous airport, residents on Tuesday overwhelmingly chose to join MARTA. Seventy-four percent of voters approved the county's contract with the agency and the new sales tax that will accompany it.

In doing so, they voted to fix a transportation mistake four decades in the making.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When MARTA was conceived in the late 1960s, it was originally intended to serve Clayton County, along with the other four core counties that comprise Metro Atlanta.

But in a 1971 referendum, all but two of the counties rejected the idea, in a vote that was propelled by white fears that MARTA would make it easier for blacks to come to the suburbs.

Today, though, Atlanta's city-suburb divide is far less clear-cut. Clayton, almost totally white 40 years ago, is now a far more populous and diverse county, with a majority-black population and significant numbers of Asians and Latinos. Its population is largely working class (median income is $7,000 below the state average) and could stand to benefit from good mass transit.

But the story in recent years has been just the opposite. Clayton was not only excluded from the MARTA system, thanks to the votes of its white forbears, but also hasn't had any public transportation at all since its bus system shut down in 2010.

For MARTA, Tuesday's vote couldn't have come a moment too soon. While Clayton County is now set to join MARTA, the agency is reeling in the areas it already serves. Ridership figures in 2013 were the lowest in over a decade, and 2014 is looking even worse — even though Atlanta's population has been increasing for years. New Census Bureau data, released in October, showed the number of Atlanta transit commuters declined by 6,000 from 2010 to 2013 — the biggest drop of any American city.

Fight sprawl with sprawl

Tuesday's referendum won't necessarily be a silver bullet for MARTA, or for Clayton County. Thanks to the region's sprawl, commuting patterns in Metro Atlanta are much less typical than in other cities, making it harder for MARTA to serve people's needs with traditional hub-and-spoke trips.

Instead, a sprawling city needs a sprawling transit agency. To thrive in its new expanded form, MARTA must embrace this reality. Now more than ever, Atlantans need to go from suburb to suburb more than they need to go downtown. Four in five Clayton commuters work somewhere other than Atlanta; at the same time, four in five people who work in Clayton County don't live there. Like Atlanta's aptly named Perimeter Center Mall, the new center of MARTA's network may well be at the perimeter.

There is little precedent for a transit agency effectively addressing a large, car-dependent suburban market in the way that MARTA should.

But if the agency manages to significantly improves commutes in Clayton County, it could be a model for other sprawling cities to follow. The region's future may well hang in the balance.

Jacob Anbinder is a policy associate at the Century Foundation, the New York-based think tank. He writes about transportation, infrastructure, and urban affairs.

-

Ex-South Korean leader gets life sentence for insurrection

Ex-South Korean leader gets life sentence for insurrectionSpeed Read South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol was sentenced to life in prison over his declaration of martial law in 2024

-

At least 8 dead in California’s deadliest avalanche

At least 8 dead in California’s deadliest avalancheSpeed Read The avalanche near Lake Tahoe was the deadliest in modern California history and the worst in the US since 1981

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more