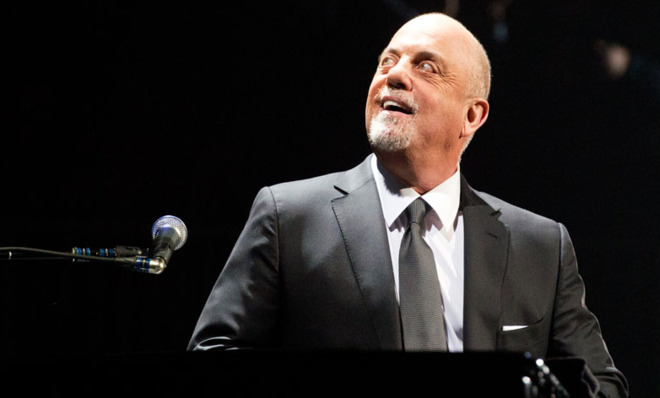

Let us now praise Billy Joel

The pop star has never been a favorite among critics. But that might be about to change.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Twenty-one years after releasing his last pop album, 15 years removed from his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, nearly a decade since his last stint in rehab for alcohol abuse, four years after undergoing double-hip-replacement surgery, Billy Joel, at 65, is enjoying an exceedingly rare moment of critical adulation and respect.

He deserves every bit of it.

One of the biggest acts in pop music history, selling something on the order of 150 million albums, Joel has been a punching bag for rock critics from the start. As Nick Paumgarten reminds readers in an admiring 10,500-word Joel profile in this week's The New Yorker, a series of self-important writers denounced him throughout the '70s and '80s for being a horribly derivative purveyor of kitsch who demonstrated consistently bad taste. The condemnations reached a peak — or a nadir — in 2009, with a comically exaggerated rant by Ron Rosenbaum in Slate that christened Joel the "Worst Pop Singer Ever."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But of course Joel isn't the Worst Pop Singer Ever. Not even close, as a widening circle of his peers has begun to acknowledge. In addition to continuing to please the legion of fans who shell out for tickets to his summertime stadium shows and (since last January) his once-a-month concerts at Madison Square Garden, Joel's reputation is on the upswing. He was honored in 2013 at the Kennedy Center, there's a highly sympathetic "definitive biography" of the musician set for release next week, and in November, he'll visit the White House to receive the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

Critics may scoff at placing Joel in the same league as Gershwin, but that's precisely where he belongs. No, Joel isn't The Best Pop Singer Ever. But at his best, he was undeniably One of the Best Pop Songwriters Ever.

Before we get to the songwriting, can we please take a moment to note that for a time in the mid-'70s Joel was hands down the best pop-rock pianist in the business? His only rival for that title, Elton John, never came close to matching Joel's chops. Don't believe me? Check out this jaw-dropping live performance of "Root Beer Rag," an instrumental off of Joel's third album (Streetlife Serenade). Or the better-known "Prelude" to "Angry Young Man" from Turnstiles. Both demonstrate uncommon technical — and compositional — skill.

This much even many of Joel's most savage critics would concede. Where they become unforgiving is the songwriting — Joel's lyrics and music — which they consider irredeemably sappy and superficial (to grab just a couple of the barbs Rosenbaum hurls at him in his Slate takedown).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is Joel the greatest lyricist in the history of popular music? Not at all. His straightforward narrative songs have none of the haunted wordplay and serrated surrealism of Cole Porter or Bob Dylan. His best effort to write the kind of working-class epic that Bruce Springsteen once excelled at ("Scenes from an Italian Restaurant" on The Stranger) borders on cheeseball. While his love songs can be touching, they fall far short of the emotional honesty and depth of Jackson Browne's finest work, while his attempts at tackling social-political topics ("Allentown," "Goodnight Saigon," "We Didn't Start the Fire") feel wooden, overly obvious, and a little maudlin.

But much of the time his lyrics are perfectly respectable and packed solid with smart-ass attitude and instantly memorable turns of phrase. And occasionally — the best example is 1976's Turnstiles — they achieve something greater. I can think of no album of the mid-'70s that does a better job of distilling that moment's gloomy, wistful mood and transfiguring it into art. The aching loss of "Say Goodbye to Hollywood"; the melancholy meditation on the era's lurches between sadness and euphoria in "Summer, Highland Falls"; the vividly evocative tribute to the "New York State of Mind"; the post-'60s cynicism of "Angry Young Man"; the strung-out blend of bleary-eyed excess and nostalgia that infuses "I've Loved These Days" — all of it is pop music of the first rank.

And then there's the album's unforgettable final track, "Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway)." Two decades into a renaissance that has left the city wealthier, cleaner, and more competently run than ever, it requires concerted effort to call to mind the New York of the mid-'70s — bankrupt, filthy, crime ridden. That tableau inspired Joel to try his hand at science fiction, conjuring a future in which some unspecified Powers That Be have rendered merciless judgment on the city's fate: "They said that Queens could stay / They blew the Bronx away / And sank Manhattan out at sea." I smiled with delight when I first heard that line as a child growing up on the Lower East Side, and to this day it still packs enough of a wallop to sends chills down my spine.

But, of course, it wasn't Billy Joel's lyrics that made him a superstar. It was the music, which is where his true greatness lies. Yes, as his defenders tirelessly point out, Joel has a rare gift for crafting lovely, insidiously catchy vocal melodies. But that's just part of it. Joel uses a stunningly broad harmonic palette, ranging far beyond the standard blues-based three- or four-chord patterns that dominate folk and rock music. In this he modeled his songwriting on Lennon and McCartney, who regularly incorporated harmonic ideas from classical music and show tunes into their songs for the Beatles. But Joel also took ideas from jazz, Tin Pan Alley tunesmiths, and other pre-rock sources. The result was a degree of harmonic complexity rarely heard on million-selling pop records.

Listen with fresh ears, if you can, to "New York State of Mind," "Vienna," "Honesty," "Zanzibar," "Stiletto," "All for Leyna," "Pressure." The last of these was the leadoff single from 1982's The Nylon Curtain, an album packed with rarely heard musical masterpieces: "Laura," "She's Right on Time," "Surprises," "Scandinavian Skies," and "Where's the Orchestra?" Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Richard Rogers, Paul McCartney — all of them would have been proud to pen any or all of these songs. Does that make them "derivative," as so many of Joel's critics have alleged over the years? Sure it does. But pop music is always derivative, drawing on multiple sources and influences and transforming them into something original, indelible, new. Which is precisely what Joel has always done in his best work.

And never more so than on his last great album, An Innocent Man from 1983. More than any of his previous records, this one was a transparent homage to an earlier era of music, the 1950s. But it's much more than that. "The Longest Time" is harmonically intricate doo-wop sung a capella, with Joel overdubbing every part himself across multiple octaves. "This Night," done in the style of Little Anthony and the Imperials, makes dazzling use of the melody from the second movement of Beethoven's Pathétique Sonata. The title track is a theatrical ballad that evokes Ben E. King and the Drifters and features the finest vocal performance of Joel's career. But the album's strongest song — and one of the greatest pop tunes of Joel's career — is "Uptown Girl."

Yes, that song — the one you've heard a hundred times, the one written, somewhat insufferably, in the throes of infatuation for supermodel Christie Brinkley. Pretend you've never heard it before and allow yourself to be swept away anew by the stratospheric melody. Marvel at the effortless harmonic modulations between the verse and the chorus, and the chorus and the instrumental bridge. And take note of how perfectly Joel's vocals recall the piercing tone of Frankie Valli. It's a perfectly realized pop gem.

After An Innocent Man, Joel released three more rock albums — The Bridge (1986), Storm Front (1989), and River of Dreams (1993) — each less accomplished than the last. Then he just stopped. (An album of classical pieces appeared in 2001.) And that's the final reason Joel deserves our honor and respect. He could have followed the path marked out by so many aging pop musicians and kept cranking out mediocre music, adding substantially to his fortune in the process. But Joel became convinced that he didn't have anything left to say, and rather than risk diluting his legacy with junk, he decided to call it quits.

If only more pop stars showed as much humility, modesty, and capacity for self-criticism as the unjustly maligned Billy Joel.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.