The uncomfortable truth in The Giving Tree

The Giving Tree is not actually a happy book. It's a tragedy about the perils of dependence.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

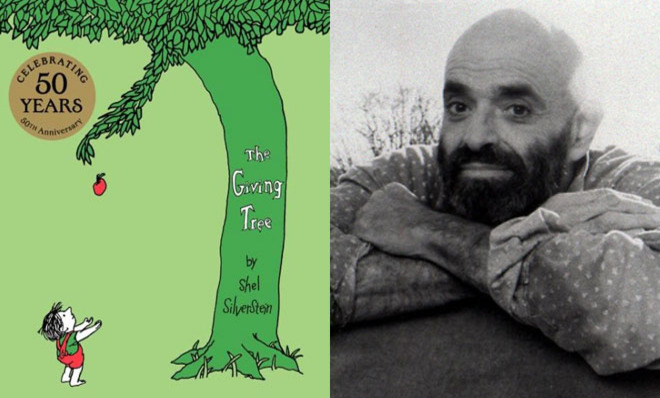

"Once there was a tree and she loved a boy." And so begins Shel Silverstein's The Giving Tree, the bestselling children's book that turns 50 this year and is still, 10 million copies later, one of the most divisive in the canon.

As its name suggests, the story is a tale about giving. The tree gives the boy her branches to hang from when he longs to play, apples to sell when he needs money, her branches to build with when he asks for a home, her trunk to carve a boat out of when he wants to get away, and a stump to sit on when he must rest his weary bones.

For its fans, the book is a parable about the beauty of generosity, and the power of giving to forge connection between two people. For its detractors, the book is an irresponsible tale that glorifies maternal selflessness, even as the maternal figure is destroyed in the process. Despite the tree being reduced to a stump, the book declares in its final lines, "the tree was happy" — a line that has made many mothers wince.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Although they land in very different places, both readings are based on the presumption that the book itself was designed to be a happy one. The thinking is that Silverstein intended the tale to endear and so he presented us with a model of giving: the character of the tree. But I don't believe the goal here was to represent the apotheosis of giving (or a Christlike figure as some interpret it), so much as the complexity of human connection.

The Giving Tree is not actually a happy book about giving, but a meditation on longing and the passing of time. The boy and the tree are just like the rest of us: they can't get no satisfaction. They are trapped in a co-dependent relationship — to use a psychological phrase —with the boy as the narcissistic taker and the tree as the compulsive enabler. Neither can break away from this pattern, which is why the ending is so tragic.

It's the misguided belief that children can't recognize the sadness or the darkness behind the caregiver relationship that pushes many to misread this story as a happy one. But children can.

They are acutely aware of the perils of the parent/child bond, as evidenced by their abiding infatuation with orphan stories. Many Disney classics feature orphans, including Aladdin, Peter Pan, Cinderella, Snow White, Elsa the Snow Queen, Mowgli from The Jungle Book — the list goes on. (There are also many who only have fathers, including Belle, Ariel, and Bambi.) Add to this the many literary characters who had no parents, including Harry Potter, Anne of Green Gables, Huckleberry Finn, and Oliver Twist. The appeal of orphans is not a recent one either; ancient folktales feature parentless children.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Orphans are the embodiment of every childhood fantasy and fear. The moment we become aware that we are separate beings from our parents, we begin to experience conflicting desires. We long to escape our parents as well as never leave their side. We revel in the comfort they provide us, but also fear their power. We worry about what might happen should we become independent, yet we struggle to gain freedom.

When a child loses her parents, the perils of dependence, as seen in The Giving Tree, are gone and she becomes an individual. In most children's literature this works out for the kid, who tends to be rewarded for their moxie with love and riches.

This is probably a good moment to say that I love The Giving Tree. It was the first book I read (or memorized, depending on who you ask). But at age 4, I didn't think about the selflessness of the caregiver. Rather, I was enthralled by the intense power that connections have to shape who we are and what we will become. Over the years I came to see the book less and less as an endorsement of giving, and more about the way love and tragedy are irrevocably intertwined, and how our giving to others inevitably detracts from how much we can give ourselves.

My son is way too young to understand any of this, but one day I hope he sees the capacity for beauty and danger in the act of giving. If he's anything like me, his first lesson will be from this book.

(Editor's Note: This article originally misidentified the movie in which Mowgli appears. It has since been corrected. We regret the error.)

Elissa Strauss writes about the intersection of gender and culture for TheWeek.com. She also writes regularly for Elle.com and the Jewish Daily Forward, where she is a weekly columnist.