Everything you need to know about cooking mollusks

Cleaning? Storing? We've got you covered.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Now that there's a nip in the air, we've got bivalves on the brain. Steamed clams. Mussels in white wine. Oyster stew. Bivalve mollusks aren't especially hard to cook, but you do need to be particular about the way you handle them. Follow these rules for cleaning and storage to be rewarded with the best they have to offer.

Signs of life: You never want to cook dead mollusks. They're dead for a reason, and we can guarantee it ain't good. Once they die, toxins build up in their tiny bodies, which they'll pass to you, no matter how much you cook 'em. Inspect your catch right after you buy the bunch and again before you cook them and toss anything dead. If you're throwing out more than a couple, be wary: "I'd worry about the toxicity of the overall batch," says Lynne Rosetto Kasper, host of American Public Media's The Splendid Table.

(More from Tasting Table: Shepherd on smoked fish)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How do you know if your bivalves are alive? Immediately get rid of anything with broken or damaged shells. Clams and mussels shells should be slightly open, and should shut quickly when you tap on them. If they're closed, don't shut, or float in water, they're dead. Introduce them to the trash. Oyster shells, on the other hand, should be closed tightly. And, as with all fish and shellfish, your bivalves should have a fresh, oceany smell with no hint of fishiness or ammonia.

Room to breathe: Your bivalves are definitely alive, right? Keep them that way by storing them properly. Never store them in plastic: They'll suffocate. (That's why most come in a mesh bag.) Instead, place them in a colander set over a shallow dish, cover with a damp towel, and store in the coldest part of your fridge.

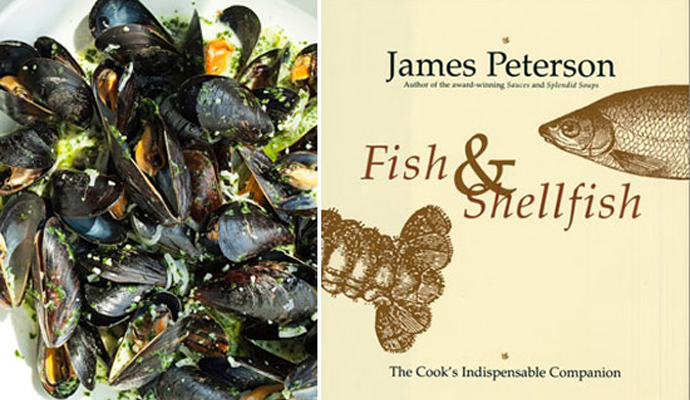

James Peterson, author of Fish & Shellfish: The Cook's Indispensable Companion recommends placing ice over the towel, and most experts recommend that you don't store them for more than two days. Don't ice your bivalves directly, as their hard shells belie a delicate flesh. "They die between 35 and 40 degrees," says Kasper. "The ideal temperature is around 33 degrees."

(More from Tasting Table: Gone bananas)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"If you really want to be a purist about it," says Nick Branchina, director of marketing for Browne Trading Co. in Portland, Maine, "store them packed in seaweed," which mimics their natural saltwater habitat.

Yes, scrub: Since most shellfish is commercially farmed, the product you're getting should be pretty clean, says Kasper. However, you'll want to give the outsides of the shells a good scrubbing to dislodge any remaining grit. Remove any beards by pinching and pulling.

Fun cleaning-related fact: Clams with darker shells (which are the result of growing in silt or mudflats) are generally easier to clean, says, Steve Woodman, owner of Woodmans of Essex, a 100-year-old Massachusetts restaurant that specializes in fried clams. Lighter shells indicate that the clams grew in sand; they'll be harder to clean.

Get rid of grit: Most hard-shell clams will be fairly grit-free. However, says, Peterson, "steamers and razor clams benefit enormously from an overnight soak in salt water." It has to do with their anatomy: Steamers (or soft-shell) and razor clams never close because of their siphon necks. "The sand isn't just in their shells — they actually ingest it, too," Branchina says.

(More from Tasting Table: Back in black)

To get rid of this pervasive grit, you'll have to purge them. Most experts recommend soaking the clams in salted water (in the refrigerator!) from an hour to overnight. Simply add salt to fresh water: "Make it taste like sea water," says Peterson. "You'll find a bunch of sand at the bottom of the bucket the following morning." Once rinsed, you're ready to steam, shuck and enjoy.

*Common wisdom advises against eating oysters and shellfish in a month without the letter "r" — May through August. There are two major factors behind this rule: Warmer waters often bring red tides and algae blooms, which contain toxins that the shellfish can absorb, causing paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP). It's also when oysters and other shellfish spawn — and a fertile oyster isn't a tasty one. Most commercial shellfish farming and fishing is highly monitored, lessening these threats. However, if you're eating wild-harvested bivalves, you may want to take more care. If you're unsure, consult your fishmonger.

Tasting Table is a culinary lifestyle brand that obsesses over what to eat and drink so you don't have to. It's like having a foodie best friend to distill the culinary world into must-do, must-eat, and must-know recommendations, on everything from the best Thai in the Village to the top tequila pours in Outer Mission. Hungry yet?

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict