The science of autumn colors

What's the story with all that red and gold? Biochemistry has the answer.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Whether you make a point of going on leaf-peeping excursions or just enjoy the turning leaves shading your street, you probably wonder what the story is behind the autumn palette of maples, oaks, birches, and other deciduous trees. The answer lies in biochemistry.

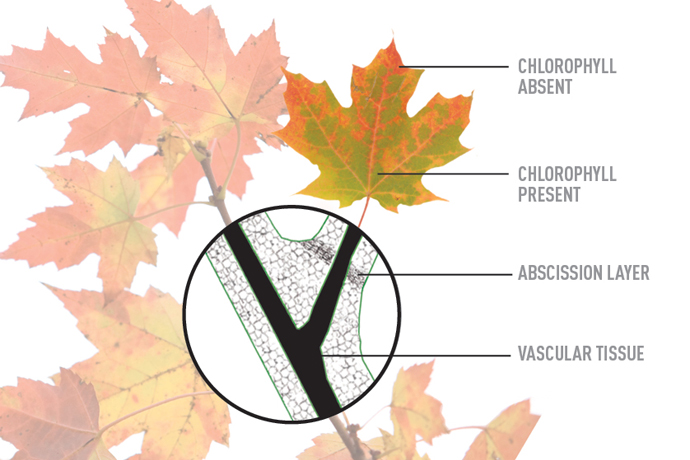

The cycle of colors in the leaves of deciduous trees is influenced by weather and temperature (more on that later), but one of the primary drivers is the lengths of nights and days, which govern a tree's growth cycle. As nights start getting longer, deciduous trees start to form what are called abscission layers at the intersection of leaf and stem. The cells in that junction begin to divide rapidly but do not expand, creating a corky seam that will eventually be the point where the leaf breaks off and falls. As this abscission layer forms, it gradually chokes off the flow of minerals and nutrients between the leaf and its branches.

(More from World Science Festival: How quantum computing could change everything)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This nutrient blockade means that it becomes harder and harder for a leaf to renew its stores of chlorophyll, the green pigment that helps plants use sunlight for food. Chlorophyll breaks down with exposure to light, just as paint fades when exposed to the sun. In spring and summer, the leaf can replenish its stores of chlorophyll with no problem, but when the abscission layer forms, it doesn't have the materials to do so. So the green of chlorophyll fades away in autumn, exposing other underlying colors in the leaf which result from other pigments.

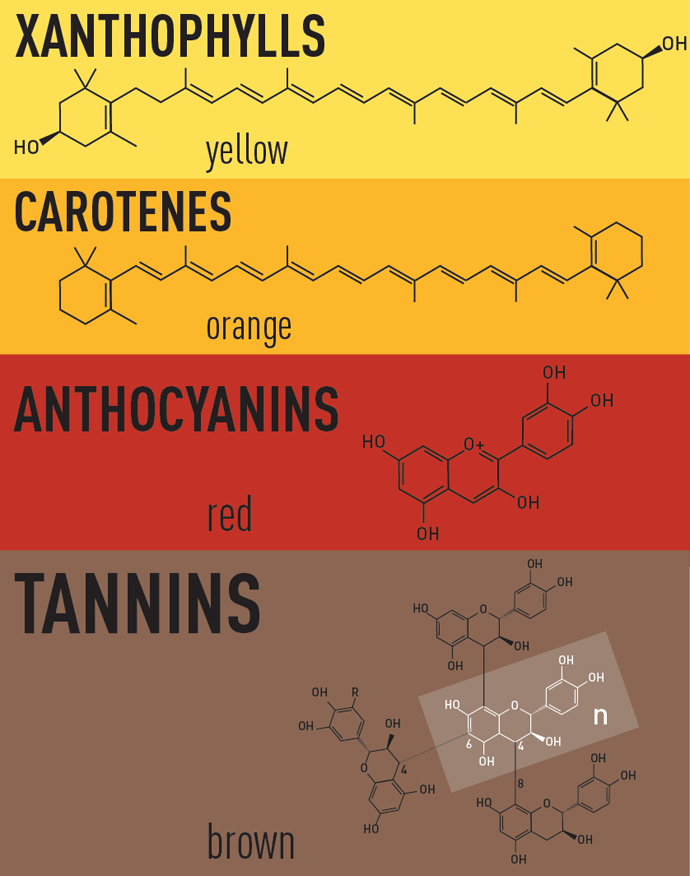

When chlorophyll steps away from center stage, the compounds that give leaves autumnal hues get a chance to shine. One family of pigments is called carotenoids, of which there are two kinds commonly found in leaves: xanthophylls and carotenes. Xanthophylls account for yellow hues, and can be seen outside of plants as well; the yellow of an egg yolk is thanks largely to the xanthophylls that chickens ingest in their plant-based feed. Carotenes result in orange-hued leaves, but you can also find them in fruits and vegetables like sweet potatoes, carrots, and cantaloupes.

(More from World Science Festival: There'd be no Steve Jobs without Grace

Carotenoids are present in the leaf throughout the growing season; they're accessories to chlorophyll, assisting in the process of photosynthesis. But the anthocyanin pigments that result in red and purple autumn colors only arise in the leaf in late summer and early fall. They're produced from sugars inside leaves, but the reaction that makes them requires a high concentration of sugar — so it can only occur after the abscission layer forms. The function of anthocyanins is still something of a botanical debate: Some researchers think these pigments absorb potentially harmful UV radiation; others suspect they deter herbivores by tasting nasty.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Just as chlorophyll fades over time, so too do the carotenoids and anthocyanins, which break down due to light and freezing temperatures. So, as fall slides into winter, bright autumnal hues are rolled back to reveal brown shades caused by tannins. These pigments, which are some of the most stable ones in the leaf, are thought to deter leaf-eaters from chowing down. You can detect the astringent taste of tannins for yourself in a glass of red wine — it derives not so much from the grapes themselves, but from the oak wood barrels the wine is aged in.

(More from World Science Festival: See how drought dries up the world)

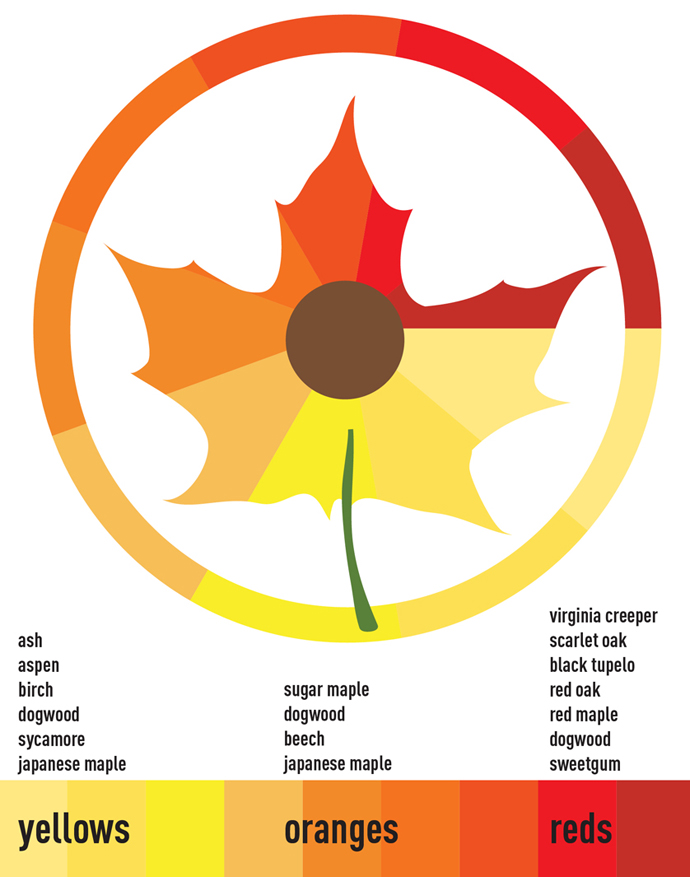

What tree gives which color? While there will always be variation within families of trees, there are some truisms. The leaves of oaks and maples tend to be redder, while those of aspen and poplar are yellow, and those of hickories in autumn tend to be bronze. The intensity of an autumn color display is also affected by the weather. Temperatures that are low, but not below freezing, are the recipe for a bumper crop of anthocyanins, and bright sunshine also helps fade chlorophyll and promote anthocyanin production. So, if the autumn weather in your area has been free of early frosts and full of warm, sunny days, and cool nights, you're probably in for an especially delightful leaf-peeping season.