Americans are sitting on lots of cash. But the Fed isn't to blame.

All the central bank has tried to do is to get people to spend, spend, spend

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How to explain America's post-2008 economic malaise?

A new paper by Yi Wen and Maria A. Arias published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis correctly fingers cash hoarding as one of the major culprits, a phenomenon that I've discussed in the past. The U.S. has a savings glut, which means that consumers, business, and banks are sitting on their money instead of spending it.

The paper notes that banks have put away close to $2.8 trillion in reserves, and that households are sitting on $2.15 trillion in savings, which is nearly a 50 percent increase over the past five years. That's in addition to the $2 trillion that corporations are hoarding.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The paper blames the glut on two factors. First, the financial crisis, which ushered in an era of gloom and pessimism that discouraged investing. No argument there.

But, problematically, the authors of the paper also blame the Fed's monetary policies for having "reinforced the recession":

In this regard, the unconventional monetary policy has reinforced the recession by stimulating the private sector's money demand through pursuing an excessively low interest rate policy (i.e., the zero-interest rate policy). [Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis]

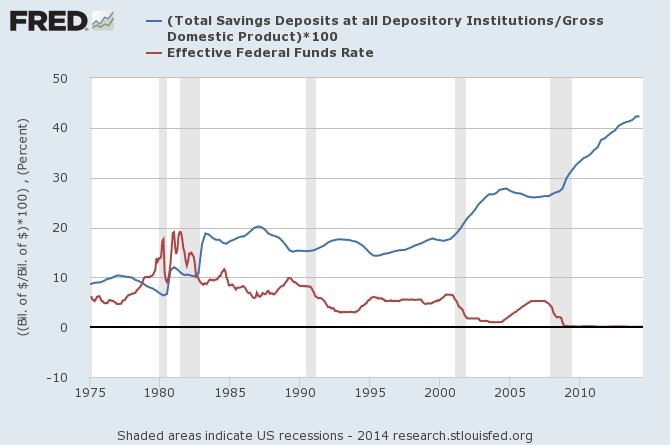

That is a superficially appealing explanation. Over the past 40 years, lower interest rates have coincided with greater savings:

(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But correlation, of course, is not causation. The reality is that greater savings have occurred in spite of low interest rates — not because of it.

The authors of the paper argue that the Fed's monetary policies have "forced investors to readjust their portfolios toward liquid money and away from interest-bearing assets such as government bonds," the idea being that interest rates are so low that it's not worth the investment.

But they do not present any specific evidence to suggest that this has occurred. And their theory flies in the face of the way interest rate policy actually works.

Lower interest rates stimulate productive activity by lowering the incentives to sit on money in any form — that includes liquid assets like cash and bank deposits, as well as yield-bearing assets like bonds. Instead, they encourage spending and investment. What the above graph really shows is that before the Fed reached the zero bound in 2008, it was able to curb the propensity to save in the aftermath of recessions, bringing the two lines closer to equilibrium.

What we see after 2008, however, is that the size of the shock spooked the economy to such an extent that the extremely low interest rates were unable to bring the cash hoarding under control. The low rate itself certainly didn't spark more saving.

If the Fed could cut interest rates below zero, it would make little sense to sit on cash that is actively losing value even before inflation. But the Fed can't cut interest rates below zero, because cash pays zero. Lower rates than zero would simply incentivize the withdrawal of money from the financial system into cash. This problem is known as the zero lower bound.

The Fed is not out of tools to incentivize productive investment — quantitative easing works, too. The fact that America's corporate cash pile is finally declining, while business investment is rising, suggests that these measures are working. But they have been slow to take effect.

Higher interest rates — which is what the paper appears to be implicitly advocating by arguing that excessively low interest rates have caused cash hoarding — would simply make the problem worse. If the authors think that cash hoarding is bad now, they should see how bad it gets when the incentives to do it are greater.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.