Wait a minute, Mr. Postman: Why postal banking won't work

Some want the U.S. Postal Service to help the millions of Americans without a bank account. But there are better solutions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The United States Postal Service just reported that it lost $2 billion in the last three months, surprising no one.

The news has once again prompted calls for the federal government's most omnipresent institution to come up with creative solutions to remain solvent in the long term. Chief among them: allowing the Postal Service to provide basic financial services like small loans, debit cards, and check cashing.

To supporters of so-called postal banking, the logic is simple. The USPS has built an impressive network of 31,000 post offices, nearly two thirds of which are in ZIP codes that have fewer than two banks. Even if it charged well below market rate for its banking services, the Postal Service could create a new source of revenue while helping the estimated 10 million "unbanked" and 24 million "underbanked" American households that do not use traditional financial institutions.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The postal banking idea has gained currency in media outlets like Vox and The New Republic. The only problem? Postal banking will neither fix the Postal Service's woes nor help the millions of Americans who aren't getting the basic financial services they need.

Rural solutions for urban problems

Our focus on the Postal Service shows just how misplaced our good intentions are. When we think of Americans who don't have access to a bank account, the image of a farmer somewhere in the rural Midwest is what comes to mind. Banking through the post office — that enduring institution of small-town America — seems like a natural solution.

Yet nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, the biggest populations of unbanked people are not in the rural middle of the country, but in its large urban areas. And rather than proximity to bank branches being a key predictor of having a bank account, the more accurate determinants are race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Out of the estimated 34 million unbanked or underbanked households in the U.S., 1.5 million are black and Latino families in the New York City metropolitan area alone, according to a comprehensive 2011 survey from the FDIC.

That includes places like New Haven, Conn., a majority-minority city with a median per capita income of just over $16,000. Connecticut has among the greatest racial disparities of any state when it comes to banked populations — while 85 percent of white residents have a bank account and do not rely on "alternative financial services" like check cashers and money orders, just 47 percent of Latino residents and 36 percent of black residents fall into that category.

As in many states, Connecticut's minorities are overwhelmingly located in cities, which makes places like New Haven prime targets for efforts to reduce the number of unbanked and underbanked.

Yet it also shows precisely why postal banking won't help. New Haven has 32 bank branches and 14 licensed check cashers, according to state and federal records. Post offices? Just eight.

Ditch the paycheck

Fortunately, the steps needed to ameliorate America's underbanking problem are not much more difficult than legalizing postal banking.

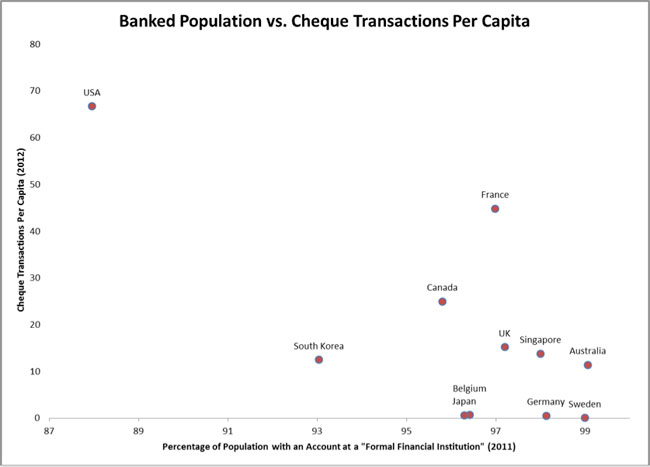

For starters, we need to wean ourselves off our addiction to checks as a form of payment. While checks are in precipitous decline, we still use them far more than any other country in the developed world. The average American writes or receives 67 checks every year, as opposed to 45 in France, 15 in the United Kingdom, and one (that's right, one) in Belgium, Germany, and Japan.

Not surprisingly, these countries also have much higher rates of bank account ownership — all have populations that are more than 97 percent "banked," versus 88 percent in the U.S.

While it is difficult to prove causation, the connection is logical. Checks can be redeemed for cash without having to go to a bank. Certain American workers may prefer to deal with check cashers — who at least charge their onerous fees up front — than banks with Byzantine fee structures.

Of course, this habit works against people's long-term interests, since it's free to deposit a check into a bank account. But in the short term, the prospect of having immediate cash seems worth the 2 percent fee that Pay-O-Matic levies on a cashed check.

Rather than convincing people of the virtues of direct deposit, though, we should tackle the root of the problem by requiring businesses to gradually phase out checks as a form of wage payment and bill pay. Not only is it better for the environment, it will save them money, too. Ironically, the USPS has been a major impediment in this effort, as check-based payments are one of the few remaining markets for First-Class Mail.

Many large companies have already come to this conclusion without government prodding. Walmart, Home Depot, and Walgreens, among others, now give their workers a choice between direct deposit and a prepaid card onto which their wages are loaded.

Use of the prepaid cards has skyrocketed in the past few years. In 2013, Americans used them to pay for $3.1 billion in purchases in 2012 — a tenfold increase since 2006.

A tangled web of fees

The rise in prepaid cards is a major step forward, but as The New York Times has reported, the companies that issue the cards operate in a legal gray area.

While their accounts are FDIC insured and they issue real debit cards, the companies' fee structures often mean that there is literally no way for workers to access their money without incurring a fee, in part because they are issued by banks that have no physical branches.

Yet not accessing their money is also costly, since the cards levy inactivity fees if the holder does not use them a minimum number of times every month.

Any long-term solution to helping America's unbanked and underbanked must fix this problem. For many people these cards are, for all intents and purposes, a checking account.

That's fine, except no one would ever choose to open a checking account with a bank that charged him or her to deposit, withdraw, and spend his or her own money. The Federal Reserve, which interprets and enforces the law on card fees, should recognize that these three particular actions are fundamental rights of banking consumers and prohibit financial institutions from profiting from them.

Dead letter

Notably, none of these solutions would do anything to help the USPS. In fact, making it easier for Americans to receive and use money electronically may actually hasten the demise of the Postal Service as we know it.

It's an unfortunate reality, but it also underscores how — nostalgia for the post office aside — helping unbanked and underbanked Americans is actually the issue more deserving of our attention. Millions of Americans today operate outside of the traditional financial system, and we are all paying a hefty price for it.

Jacob Anbinder is a policy associate at the Century Foundation, the New York-based think tank. He writes about transportation, infrastructure, and urban affairs.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day