Inside the mystery serum that could save Ebola victims

ZMapp is a mixture of antibodies harvested from the immune systems of Ebola-infected mice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Earlier this month, Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol were close to death. The two American aid workers infected with the deadly Ebola virus were flown from Liberia to Atlanta, Georgia, where they were promptly sent to the Emory University Hospital. At the moment, there is no officially approved treatment or vaccine for the Ebola virus, which has a 50 to 90 percent mortality rate. But Brantly and Writebol were each given doses of an experimental anti-Ebola serum that had never been tested in humans. Soon after, according to Emory University doctors, both patients were improving.

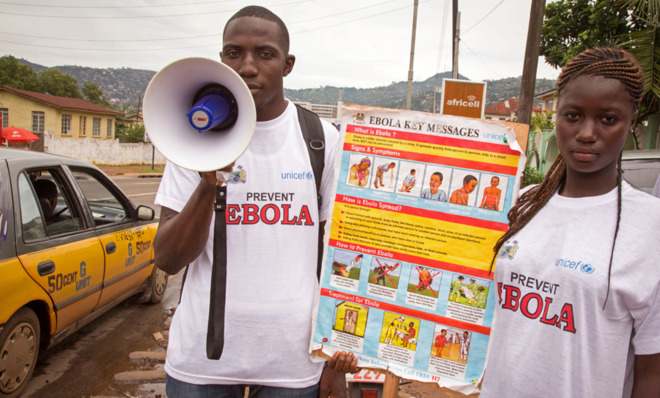

Named after the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, near where the first outbreak occurred in 1976, the Ebola virus causes fever, muscle pain, vomiting, and diarrhea, among many other symptoms. The Zaire strain at the center of the current outbreak in West Africa is the most fatal of the five known strains. Though highly pathogenic, the virus is not airborne and can only be transmitted via bodily fluids.

(More from World Science Festival: Why lethal injections fail)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The experimental drug administered to the infected aid workers, called ZMapp, is one of a number of treatments that have shown some promising results in animal models. Developed by San Diego-based company Mapp Biopharmaceuticals Inc., ZMapp comes in the form of a serum, which is a portion of blood that contains antibodies — the disease-fighting proteins that bind to harmful substances (called antigens) and either neutralize the threat directly or flag down other immune system cells to do the job. A serum is different from a vaccine, which uses either a similar or weakened version of a disease-causing agent to stir up a person's immune system to produce antibodies against that pathogen. There are a couple approaches to making anti-Ebola serum. One uses antibodies from humans who have recovered from Ebola infection; another uses antibodies obtained from infected lab animals to create what's called a monoclonal antibody.

ZMapp is the latter, a mixture of three monoclonal antibodies harvested from the immune systems of Ebola-infected mice. One of the challenges in developing this kind of serum is finding the right combination of antibodies that bind to a virus to keep it from replicating itself. As John Timmer at Ars Technica explains, our immune system is likely to attack these foreign mouse-borne antibodies, so part of the process in making ZMapp involves removing and replacing mouse portions of the antibody genes with human genetic material. Then, the antibody genes are implanted into the cells of tobacco leaves, which produce more of these synthetic antibodies and thus, more ZMapp.

Whether a serum is developed synthetically or obtained from a recovered person, it's hard to evaluate or compare the efficacy and safety of anti-Ebola treatments. This is because few of these drugs barely make it past the first phase of the FDA drug approval process, according to Charles Chiu, an infectious disease physician at the University of California, San Francisco. One of the Ebola-specific roadblocks to this approval process arises when it comes to testing these drugs on human subjects. Because the virus infects people in remote parts of the world served by little or poor infrastructure, transporting the drugs to these places and administering them presents major logistical challenges.

(More from World Science Festival: Could phasers and tricorders happen? Star Trek science)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

ZMapp was selected after the Samaritan's Purse, the charity Brantly and Writebol were working for, reached out to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC then referred Samaritan's Purse officials to a National Institutes of Health researcher who consulted with them on experimental treatments for Ebola.

Mapp Biopharmaceuticals has also explored using monoclonal antibodies to treat as well as prevent Ebola. In research published in Science Translational Medicine, Mapp researchers provided a monoclonal antibody cocktail to rhesus macaque monkeys within 48 hours of infection. With that serum, known as "MB-003," 43 percent of the treated monkeys survived, while none survived in the control group. By January 2014, ZMapp, a mixture of MB-003 and another serum developed by Toronto-based Dreyfus, Inc., officially became an anti-Ebola drug candidate.

(More from World Science Festival: A plutonium delivery in the desert)

While Brantly and Writebol's current status is encouraging, it's hardly the death knell for Ebola. "It would be premature to conclude that these patients recovered because of this treatment," says Daniel Bausch, a Tulane University professor of tropical medicine. "Especially considering that these patients worked for this humanitarian organization; there are a lot of resources they had access to that other patients don't, like one-on-one care and more aggressive fluid management." There are many unknowns in treating Ebola; more clinical trials, human subjects and diverse settings will be needed to determine this promising serum's full potential.

-

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonadeTODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns

-

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day