Ghosts of the Freedom Summer

One writer's first visit to Mississippi led her to discover her family's hidden history

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

IN 1947, MY father, along with his mother and older brother, boarded a northbound train in Greenwood, Mississippi. They carried with them nothing but a suitcase stuffed with clothes, a bag of cold chicken, and my grandmother's determination that her children — my father was just 2 years old — would not be doomed to a life of picking cotton in the feudal society that was the Mississippi Delta.

Grandmama, as we called her, settled in Waterloo, Iowa — a stop on the Illinois Central line and a place where thousands of black Mississippians would find work on the railroad or at the Rath meatpacking and John Deere plants. Grandmama took a job familiar to black women: working for white families as a domestic.

Almost every black person I knew growing up in Waterloo had roots in Mississippi. Mississippi flavored our cuisine, inspired our worship, and colored our language. Still, when speaking about the land of their birth, my dad and grandmother talked about family and loved ones, but seldom about the place.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Mississippi was at once my ancestral land and the sinister setting in any number of Hollywood movies, a villain in our national narrative. The only image of Greenwood I got from my family was of my great-grandparents' farm; scenes of chickens and picking peas in the morning sun; and my great-grandmother, Mary Jane Paul, refusing to take any mess. It was only when I got older that I learned my family did not in fact own the farm.

Though my parents would load us all in the car every summer to head to a different state for our family vacations, my dad never once took us to the state of his birth. Not for family reunions or funerals. Not for graduations or holidays.

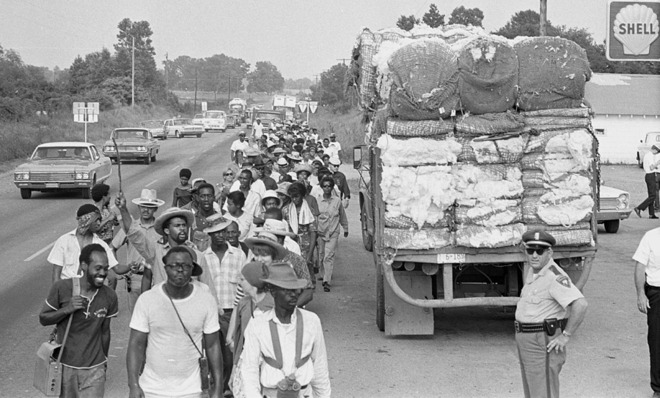

As the nation prepared this year to mark the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer — that violent and heady 10 weeks during which Northern volunteers joined forces with Southern activists in Mississippi, all working to meaningfully enfranchise black residents — I felt pulled to finally visit this place that ran in my blood but that I had never seen. This June, I visited Mississippi for the first time.

MY 87-YEAR-OLD GREAT-AUNT, Charlotte Frost, who had followed my grandma to Waterloo, happened to be visiting a granddaughter in Jackson at the same time I planned my trip. I picked up Aunt Charlotte, and we headed north on U.S. Highway 49 toward Greenwood, into the heart of the Delta and Freedom Summer's ground zero.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As we drove, I tried to get my Aunt Charlotte to open up about what it was like coming of age in a black family in the Delta. But she said she never had any problems with white people, that they had respected her family and hadn't done much to bother them.

It was a familiar take. She and another great-aunt in Waterloo are the last of my Grandmama's siblings, and I had tried before to get their stories. I never push too hard at this gauzy version, because I know that women like my great-aunts — they pride themselves in their durable dignity, dress to the nines, don't use vulgar language, and keep impeccable homes — have no desire to speak of the daily degradations they'd faced at the height of Jim Crow.

A wooden sign coated in brown paint announced our arrival: Welcome to Greenwood, Cotton Capital of the World. But it was clear from the rows of lanky corn stretched out before the sign — not exactly squat June cotton — that the greeting's boast was mere nostalgia.

We headed to the Little Zion Missionary Baptist Church just outside of town. The plain, white structure was where our family worshipped. My great-grandmother and great-grandfather, Mary Jane and Percy Paul, part of the first generation born out of slavery, are buried in the overgrown cemetery.

According to Aunt Charlotte, the church used to be a part of the Whittington Plantation, the white landowners having built it for the black sharecroppers. It's still surrounded by crops, and Aunt Charlotte, stooped over her cane, pointed to a distant spot in the fields, saying their house, the house where my great-grandmother helped deliver my father, once stood there on the Whittington lands.

It was dusk and the Delta heat settled about my shoulders like a wool blanket. Aunt Charlotte, wrapped in a memory, paused to listen to an owl hooting.

"The old people would say someone is going to die," she said.

GREENWOOD'S YAZOO RIVER is formed by the meeting of the Tallahatchie and Yalobusha rivers, and as we crossed the Yazoo River and headed to the heart of Greenwood, the ghosts of Mississippi grew close and Aunt Charlotte finally loosened.

Aunt Charlotte told me that she was baptized in the Tallahatchie. She went on to speak of another river baptism, into the perils of the Delta's color line.

She said her brother Milton — my dad's namesake — and a cousin had once committed the sin of walking through a white neighborhood for a reason other than to simply go to work. Two white teenagers in a car gave chase. Her brother and cousin were forced to jump into the murky river to escape. They returned home, muddy and wet, chests heaving from panic and exertion.

It was just a few miles outside of town where they found the body of Emmett Till. The tossing of black bodies into the muddy rivers for breaching the social order wasn't unusual. The only reason people across the nation knew Till's name was that his mother insisted on an open casket and allowed the ghastly photos of his mutilated corpse to be seen in the nation's leading black publications.

It was eerie being down here where it happened, just a few miles from where my dad grew up, and realizing how easily he could have been Till. We somehow convince ourselves that this is ancient history. But I am not even 40, and my dad was but four years younger than Till. Like my dad, Till's mother had also left as one of hundreds of thousands of black Mississippians who fled their homeland during the Great Migration.

THE REV. WILLIE Blue joined the Mississippi civil rights movement in 1963. Blue, who returned home to Tallahatchie County after a stint in the Navy, had been getting pressure from whites to find work on a plantation or to get out of town. Blue instead headed to Greenwood, where he hooked up with Bob Moses.

Moses, a Harvard-educated New Yorker, had come to Mississippi in 1961 to work on voter registration for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, known as the SNCC. Moses set up SNCC's headquarters in Greenwood — and Blue's first task was to pick up Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier, who were coming to Greenwood to offer their support.

Blue arrived at the airport only to encounter a cadre of armed Ku Klux Klan members. The two-car delegation picked up their Hollywood guests, and Blue soon found himself in a high-speed chase with the Klan. Laughing ruefully today, Blue said he didn't find out until later that Poitier and Belafonte had been carrying tens of thousands of dollars in cash to help the voting rights effort.

Moses said the 1963 killing of Medgar Evers was the turning point. Byron De La Beckwith followed Evers home and shot him through the heart with a rifle. Evers was carrying a box of T-shirts proclaiming "Jim Crow Must Go."

It was time to up the ante.

So the notion was hatched to recruit college students from across the country who would converge on the state for 10 weeks. The goal: to register enough disenfranchised black voters to challenge the all-white Democratic delegation at the national convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and instead seat the biracial Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Black Mississippians had attempted to desegregate schools and lunch counters, movie theaters, and swimming pools. But sit-ins to eat at an integrated restaurant were one thing. Pushing to access the vote in such a heavily black region was something else.

"If we get the right to vote, we become captains of our own ship," said Blue. "I believed that then; I believe that now."

The toll on black bodies during the effort to ensure voting rights is, for people of my generation, inconceivable. In the years leading up to Freedom Summer, black Mississippians agitating for civil rights were beaten by mobs, castrated, dragged behind cars with ropes, bombed. None of this was done in secret: Among the murderers were a state legislator and a county sheriff.

Freedom Summer organizers calculated that for the vote push to work, a significant number of the student volunteers needed to be white.

"We know what they bring with them are the eyes of the country," Moses told me. "The country is able to see through their eyes what they weren't able to see through ours."

Of course, most everyone knows what happened next. As Freedom Summer began, three civil rights workers — Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, two white Northerners; and James Earl Chaney, a black Mississippian — disappeared in Mississippi.

"There is no kidnapping in Mississippi," Blue reminded me. "We knew they were dead."

But the murders of those two white men changed everything. "These were not just white folks," they were "America's finest, America's futures," Blue said. "Goodman's richer than whipped cream. He wasn't supposed to die in Vietnam; he sure wasn't supposed to die in Mississippi. When America's brightest are murdered for doing something fundamentally American, suddenly the world knows about Mississippi. It was another nail in the segregated coffin."

WHEN I DROVE my great-aunt back to Jackson, she had casually pointed at a restaurant named Lusco's that had been in that exact location when she was a child. Of course, as a child she'd been barred from eating there. I immediately decided that I would eat there that night.

Lusco's was founded in 1921 by Italian immigrants who solidified their assimilation process by banning black diners. Five generations later, the restaurant is still owned by the same family.

I stood outside and talked to the hostess who'd stepped out for a smoke. As I talked to her, a boisterous older white couple, probably in their 70s, came out. The woman was charming and seemed used to attention. I was told that everyone simply refers to her as "Mrs. Greenwood." Mrs. Greenwood asked me and the photographer with me where we were from.

Just then, two young black men walked by. Quietly, eyes down, they headed to the store at the corner. Mrs. Greenwood's eyes followed them, and a sneer curled her lips.

"That's what you call our 'local color,'" she said. The last word, which she pronounced CAH-la, sounded mean and hard to my ears. Perhaps I blanched, because Mrs. Greenwood tried to recover.

"I'm not being ugly," she said. "It's not safe here."

I went back to my hotel room and wrote in my notes, "The Delta can be devastating."

Condensed from the original.