5 delightful science experiments from 100 years ago

Caution: Some of these are pretty dangerous...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1892, the dubiously named Mr. Tom Tit published a book of at-home activities for children called Magical Experiments: or, Science in Play. He made sure each scientific exploration could double as a parlor trick; something exciting and strange to impress as well as instruct.

Some of his experiments are all but impossible to do today (even if you can find spermaceti candles, you really shouldn't use them), and some of his once common ingredients haven't been available at drug stores for decades. But that doesn't mean you can't do them. If the product still exists, you can find it online. This accessibility re-opens a whole forgotten world of fantastic science fun, one that leaves the tired vinegar and baking soda volcanoes looking hollow.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

You'll need: Empty champagne or wine bottle with cork, baking soda, tartaric acid, a notecard rolled into a tube, thread, wadded paper, two pencils, and thumbtack.

The trick: The original text phrases it better than I ever could:

Would you like to imitate at table the explosion of cannon, listen to the thunder that frightens nervous people, and even observe the actual recoil of your artillery? You may safely answer, "Yes;" for the experiment I now propose is a quite harmless one, as you shall see.

Fill the bottle a third full of water and dissolve "a certain quantity" of baking soda into it. (My guess is, the more soda the bigger the bang, so you may want to start small). Pour the tartaric acid into the rolled up note card (again, amounts aren't specified, so best start small) and plug it with pellets of wadded paper. Tie the roll with a thread that you then pin to the underside of the cork with the thumbtack. Replace the cork. The roll shouldn't touch the water until you've laid the bottle on its side, on top of the pencils. Then, the paper with dissolve, the tartaric acid will meet the baking soda, and BOOM, your bottle blasts forth its cork missile and rolls back upon its gun-carriage (pencils), just like a real cannon.

The science: Baking soda is a base, tartaric acid is, of course, an acid. When the two combine, carbon dioxide gas is quickly created. This gas is much less dense than the powders it came from, and needs more room. Blasting the cork out of the bottle is one of the ways it makes that room.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

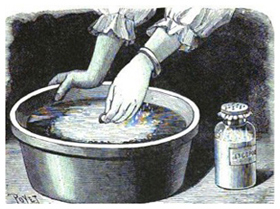

You'll need: Bucket or pot of water, small object that will sink, and lycopodium powder.

The trick: First, stomp out anything flammable within a 10-foot radius. Then, submerge any little object, like a ring or coin, in your pot of water. Next, apply a liberal puff of your "magic powder" to the surface of the water. Finally, reach your hand into the water and retrieve the object. When you pull your hand out, the object will be wet, but your hand, even though your audience saw you soak it in a bucket of water, will be completely dry. Huzzah!

The science: It's the miracle of a fat little clubmoss called Lycopodium. I say fat because the spores of this plant, when dried, have an amazingly high fat content. The resulting powder is highly flammable but quickly burns out, which is why it is popular as a flash powder for magicians (and often sold under the name "Dragon's Breath.") But more importantly, all that fat hates water. When you reach slowly through the powder, it forms a waterproof glove around your hand, repelling water molecules and allowing you to stay dry in the process.

You'll need: A strong chair and a small treat, someone strong to "spot" Tantalus.

The trick: Thirsty Tantalus was cursed forever to reach for a pool of water that dried up as soon as his hands came near. Here Tantalus just has to pick a taffy up only using his mouth, while not falling off a dining room chair that's been placed on its front legs. Unless Tantalus figures out how to maintain his center of balance, the chair will begin to tip (hopefully into the arms or sofa cushions waiting to catch such an unbalanced snacker).

The science: There is no more fun way to learn about physics than through candy and improper use of mother's good chairs. In this experiment, we use those tactics to explore center of mass. You and the chair each have your own, but you're also sharing one. When you put weight toward the candy, you defy your joint center of balance and the chair responds to the insult by throwing you off. However, if you crouch low (the lower the center of mass, the easier it is to balance) and give as much weight as possible to the heavier end of the chair, you can maintain your center of gravity and retrieve the candy.

You'll need: Oil and vinegar, a sealable clear container, and a dinner party

The trick: This experiment is described in the form of a story about a "jolly company" on a picnic together. This company is distraught to see that the man responsible for bringing the oil and vinegar salad dressing saved himself the trouble of carrying two bottles by mixing them together. Not everyone likes the same proportions of oil and vinegar on their salads, after all. So they are astonished when the young men walks around the picnic, distributing both the oil and vinegar, from the same bottle, in the exact proportions requested by each diner. How does he manage it?

The science: We know that a lot of liquids mixed with oil immediately separate. This is because the lipids in oil don't like water molecules, but they love their fellow fat molecules. Vinegar is mostly water, so the two liquids naturally separate when allowed to settle. The oil floats to the top of a bottle and is easily poured out. When the vessel is slowly turned upside down, both components stay put, so the vinegar is now right near the mouth. So, for oil, just tilt the bottle and pour very slowly. For the vinegar, turn the bottle upside down and open the mouth just a little.

5. Automatic drinking fountain for pets

You'll need: A bottle (plastic is fine) that you can affix upside down to or against a wall (it must be removable). A shallow pan and water.

The trick: Technically this device was meant to water barnyard fowl, but it should work just as well for any small animal. The device isn't so much a trick as it is a clever solution to what must have been a common problem: disgusting water-troughs for outdoor animals. The bottle is set up so that the mouth does not quite touch the bottom of the pan, but goes halfway below the brim. The pan will fill with water, but only to the level of the water inside the up-turned bottle mouth. Every time a significant amount of water is drunk, or even evaporated, fresh water comes forth to replace it.

The science: Atmospheric pressure! Water is only able to flow out of the bottle because the bottle is simultaneously sucking in air, trying to match the air pressure of the air outside. But once the water level of the pan rises to the same level as the water in the upturned bottle, the mouth of the bottle is sealed. No more air can enter the bottle to displace the water. At least not until enough water is drunk.

**All images courtesy Google Books: Magical Experiments: Or, Science in Play**

Therese O'Neill lives in Oregon and writes for The Atlantic, Mental Floss, Jezebel, and more. She is the author of New York Times bestseller Unmentionable: The Victorian Ladies Guide to Sex, Marriage and Manners. Meet her at writerthereseoneill.com.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky