Why lethal injections fail

The botch rate for lethal injections is about 7.1 percent — compared to 3.1 percent for hanging and 1.9 percent for electrocution

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Euthanizing lab animals is a routinely regulated and reviewed process. It's subject to constant revision by veterinary associations and animal care committees at labs and universities, conducted by trained technicians, and reevaluated by ongoing research.

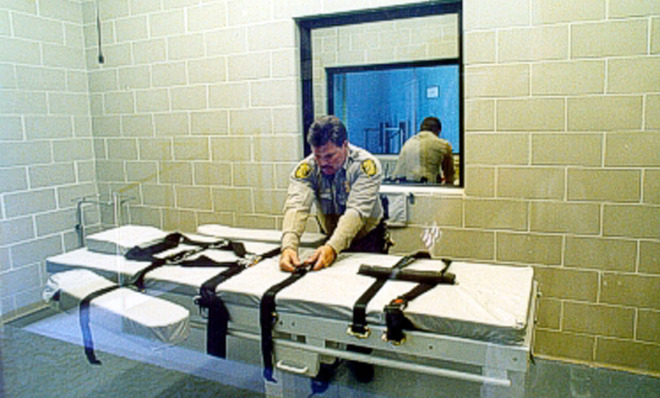

The three-drug lethal injection procedure used to execute human prisoners across the U.S. for decades was improvised by Oklahoma state medical examiner Jay Chapman in 1977, has not been refined with the input of even basic scientific research, and would be illegal to use on animals in most of the states where it's used to execute humans.

Ideally, each of the ingredients in the classic three-drug cocktail of lethal injection should be enough to kill quickly: the anesthetic sodium thiopental, the neuromuscular blocker pancuronium bromide, and potassium chloride, which stops the heart. In practice, the story is much different.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Most U.S. states jealously guard the details of lethal injections, but what execution data that researchers do manage to get their hands on shows that the drugs are often being administered at levels not large enough to kill. In a 2005 paper published in The Lancet, researchers looked at toxicology reports for 49 inmates executed in Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Forty-three of the inmates showed blood concentrations of thiopental lower than the amount recommended for surgery; the levels of the drug shown in 21 patients were low enough to be "consistent with awareness" during the procedure, the scientists wrote.

(More from World Science Festival: Five legitimate scientific controversies)

But in general, it's hard to reliably gauge the circumstances of most lethal injections because "in most U.S. executions, executioners have no anesthesia training, drugs are administered remotely with no monitoring for anesthesia, data are not recorded, and no peer review is done," the authors of a 2007 paper published in the journal PLoS Medicine wrote.

The PLoS Medicine paper analyzed execution data released by North Carolina and California, along with lethal injection drug research conducted on humans and animals in laboratories. Ultimately, they found, neither the sodium thiopental nor the potassium chloride dosages given to prisoners proves to be reliably fatal, leaving many inmates dying through prolonged, chemically induced asphyxiation from the paralysis caused by pancuronium bromide.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Even if lethal injection is administered without technical error, those executed may experience suffocation," the authors wrote. Thus, "'the conventional view of lethal injection as an invariably peaceful and painless death is questionable.'"

Technical errors can cause even more gruesome deaths. In 2006, Florida inmate Angel Diaz lingered for 34 minutes after the lethal drugs were injected when his executioners missed the veins during the intravenous catheter insertion; the drugs instead were pumped into the soft tissue of his arms, causing large chemical burns where Diaz's skin sloughed off. In April 2014, Oklahoma death row inmate Clayton Lockett died nearly two hours after entering the execution chamber; the team spent nearly an hour trying to find a proper vein, and once the IV was inserted in the femoral vein near Lockett's groin, something went wrong (the state later said the vein "collapsed," but an independent autopsy blamed shoddy placement of the IV).

(More from World Science Festival: A plutonium delivery in the desert)

A lot of these technical botches occur because most physicians and nurses refuse to participate in executions. The American Medical Association advises against participation by its members (aside from certifying the death); since 2010, the American Board of Anesthesiologists has said it will revoke the certification of any member that aids an execution. "Physicians should not be expected to act in ways that violate the ethics of medical practice, even if these acts are legal," J. Jeffrey Andrews, the secretary of the ABA, wrote in a May 2014 letter. "Anesthesiologists are healers, not executioners."

In recent years, Chapman, the medical examiner that devised the current lethal injection procedure, has said that an overdose of a single barbiturate, as used to put down animals, may be preferable to the three-drug procedure. "Hindsight is always 20/20," he told The New York Times.

Already, many states are starting to switch up the procedure out of necessity. The European Union banned the sale of eight drugs, including sodium thiopental, for use in lethal injections. Drug maker Hospira stopped making sodium thiopental in 2011, cutting off what had been the sole supply of the drug for execution. In 2013, Florida began using a sedative called midazolam that had not been tested for use in executions. In 2013, Missouri initially turned to an anesthetic called propofol, prompting the drug's German maker to start placing restrictions on distribution of the drug and raising the prospect of a shortage in hospitals. The state switched to another drug, pentobarbital, which has emerged as the current favorite in single-drug executions.

With big drug companies skittish about providing lethal injection drugs (a very tiny market with disproportionately high bad PR), states are turning to smaller compounding pharmacies to produce the fatal ingredients. This has prompted another wave of lawsuits, as the states typically refuse to provide information on the pharmacies, which are not as strictly regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as drug manufacturers. Human rights groups and prisoners' legal teams say the secrecy prevents them from knowing if the drugs are being prepared properly and how effective they'll be at delivering a quick, humane death. The quality of compounded drugs tends to vary more than the batches made at more tightly regulated manufacturers.

(More from World Science Festival: Why is HIV so hard to kill?)

The story of lethal injection is deeply intertwined with its failures. Amherst College researcher Austin Sarat, in his study of 9,000 U.S. executions (representing almost all carried out between 1890 and 2010) found that the botch rate of lethal injections was about 7.1 percent, compared to 3.1 percent for hanging and 1.9 percent for electrocution. So why is the shoddiest procedure, comparatively, still preferred?

"Using drugs meant for individuals with medical needs to carry out executions is a misguided effort to mask the brutality of executions by making them look serene and peaceful — like something any one of us might experience in our final moments," U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Chief Judge Alex Kozinski wrote in July. "But executions are, in fact, nothing like that. They are brutal, savage events, and nothing the state tries to do can mask that reality."

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day