The shameful secret behind the popularity of spy movies

They're a comforting fiction in a frightening world run by villains and fools

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Moviegoers love spies. James Bond is probably the most successful franchise in history. And when you consider all the spinoffs, descendants, books, television shows, and media-spanning imitators, it's probably fair to say that spying is one of the top two or three subjects of popular media in America, along with superheroes and light sabers.

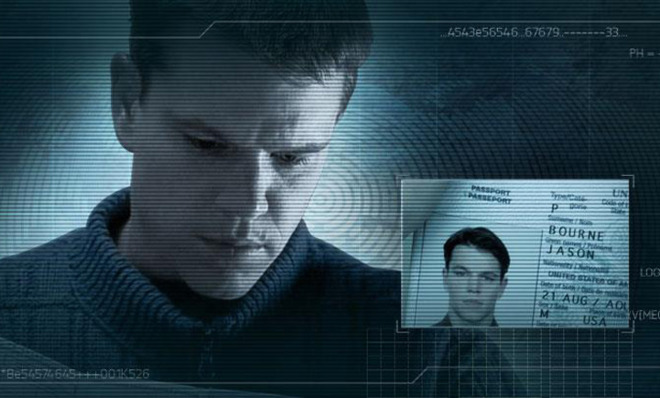

Most spy fiction portrays spies as noble and almost superhumanly skilled, both physically and intellectually. James Bond is always a master at whatever the screenwriters can dream up, up to and including sword-fighting with a half-dozen different kinds of blades. Jason Bourne speaks a dozen languages, fights like an MMA specialist, drives like a rally car champion, and can break into CIA headquarters without even breathing hard.

This could not be more dissonant with the reality of spy practice, which particularly in American history is chockablock with buffoonish incompetence, bloody failure, and "success" of the grimly horrifying sort.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So why do we love spy movies when they represent such a nonsensical fantasy? Because they serve as a crucial legitimation device for the modern state whose terrible reality and breathtaking incompetence we just can't bear to face.

James Bond rose to pop culture icon status during the Cold War, when America and the Soviet Union repeatedly came terrifyingly close to all-out nuclear war. (He's a British agent, of course, but they're perhaps our closest ally, and the movies and perspective are thoroughly American.) I imagine there was a deep societal need to believe that the agencies tasked with understanding and countering the enemy were competent and effective — a need that continues in the present day, with a fight against terrorism that shows no sign of ending. Many Americans fear existential threats from foreign enemies, and have a deep need to believe that supersmart, supercharming, superskilled superspies are protecting us.

Even the Bourne movies, which are highly critical of the United States' security apparatus, can't help but reinforce this perception. The government-trained assassins in these films are nearly omnipotent.

I mean, come on. This is just laughable.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now of course, filmmakers in all genres take creative licenses. Action movies are not documentaries. But when it comes to spies, the film fiction is so removed from reality that it raises the question of why. And the answer is that we need to believe spies are supermen. Because a movie grounded in the reality of American spycraft would be the blackest Keystone Kops–style comedy, where incompetent, half-trained alcoholics trample the ideals of American democracy for no purpose or benefit. Reading the history after the fact is to be astonished we managed not to blunder ourselves into nuclear war.

Of course, no Hollywood studio is going to create a hugely successful franchise based on Dr. Strangelove. It would simply be too depressing. It's much more compelling and entertaining to watch beautiful young people being extreme bad-asses around the world.

But the desire to believe that our bloated security apparatus is in fact doing something worthwhile, and with extreme competence, is also a part of the story. To know the truth — that our security and intelligence agencies are largely incompetent and pointless — would be extremely disruptive to the American self-image.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.